|

Using data from a population-based study, researchers from the University of Washington recently found that ingestion of dietary sources of nicotine — as found in various plants in the Solanaceae family, such as tomatoes (Solanum lycopersicum), potatoes (S. tuberosum), and peppers (Capsicum spp.) — may reduce one’s risk of developing Parkinson’s disease. The findings were published online in May 2013 in the scientific journal Annals of Neurology.1

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive, neurodegenerative disorder that is estimated to affect approximately one million Americans and up to 10 million people worldwide. For perspective, the number of Americans living with PD currently exceeds the number of individuals suffering from Lou Gehrig’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and muscular dystrophy combined.2 PD is largely known for its often-debilitating motor symptoms, including tremors of the extremities, muscle rigidity, bradykinesia (slowness of movement), and difficulty with balance and coordination. Other non-motor symptoms include dementia, pain, disturbances in sleep, and confusion. According to the Parkinson’s Disease Foundation, healthcare costs associated with PD in the United States alone are estimated to be approximately $25 billion a year.2

Interestingly, a large body of scientific research supports the idea that smoking tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum) can markedly reduce one’s risk of developing the disease. Of course, this finding does not change the well-established dangers of smoking and tobacco use, including increased risks of developing cancers, heart disease and stroke, and respiratory disorders.3 Still, the relationship between smoking and an apparent PD risk reduction has prompted researchers to further investigate the potential reasons behind this correlation.

“One of my main research interests is trying to tease this apart, and understand what about tobacco or smoking might possibly be beneficial with regard to Parkinson’s disease,” said Susan Searles Nielsen, PhD, the lead researcher of the recent Annals of Neurology paper (email, May 15, 2013). “I first got interested in studying foods in the same botanical family as tobacco when we observed that environmental tobacco smoke was associated with a reduced risk of PD. While it remains to be seen whether this finding will be replicated as frequently as that for active tobacco smoking, it did suggest that if the Parkinson’s-tobacco association is due to something in tobacco — including at levels found in environmental tobacco smoke — then maybe eating foods from plants in the same botanical family might be protective as well.”

Parkinson’s Disease and Brain Chemistry

Although there is not yet a cure for PD, symptomatic treatments are available that aim to restore brain dopamine levels, which are reduced in Parkinson’s patients and are thought to be partially responsible for some of the motor-related symptoms. Nerve cells, or neurons, in a part of the brain known as the substantia nigra are particularly affected. These neurons are largely dopaminergic (i.e., they release dopamine, which is involved in movement and coordination).

One of the most well-known components of tobacco, which is also a member of the Solanaceae family, is the addictive substance nicotine.

“It’s known that nicotine stimulates the release of dopamine in the brain, and dopamine in Parkinson’s disease is deficient, so if nicotine were stimulating the release of dopamine it might be beneficial,” said Maryka Quik, PhD, a scientist in the Center for Health Sciences at SRI International, an independent, nonprofit research organization (oral communication, May 22, 2013). “So people started looking at nicotine for its ability to prevent or reduce nigrostriatal damage and they found that nicotine was a component that could participate in this process. That doesn’t mean there isn’t something else in tobacco that might also help; we don’t know that yet. But it does appear that nicotine does something.”

Nicotine acts on a particular type of receptor in the brain known as the nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Acetylcholine, like dopamine, is a neurotransmitter that also acts on a second type of receptors called muscarinic acetylcholine receptors, which are activated by muscarine, a component of some wild mushrooms (e.g., Amanita muscaria).

“The nicotine — or the acetylcholine — both act on nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, which then releases dopamine. So the nicotine is first stimulating the nicotinic receptor, which is linked functionally to the dopaminergic system, so you get dopamine release,” explained Dr. Quik. “The brain is interconnected, which makes it so difficult to understand what is going on. It’s complicated.”

Dietary Nicotine from Solanaceae Sources

Dr. Searles Nielsen and her colleagues looked specifically at peppers, tomatoes, tomato juice, and baked or mashed potatoes, using previously established dry-weight nicotine concentrations, and tested for any potential associations between consumption of these foods and PD.

The study included 490 recently diagnosed PD patients and a control group of 644 individuals matched by sex, age, race, and ethnicity to the patients who had the disease.

“The type of study we did is commonly used to try to understand what exposures increase or decrease risk of developing a disease,” said Dr. Searles Nielsen. “You start with a group of people with the disease, preferably recently diagnosed to help ensure that your findings relate to the disease’s cause and not the effects of the disease or factors related to survival with the disease. You then find a group of people without the disease who are comparable to the other group and who you likely would have located and included in your study if they had developed the disease. Then you compare the two groups of people in terms of exposures that happened before the disease occurred.”

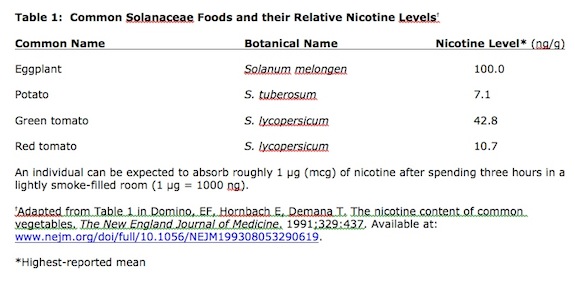

Dr. Searles Nielsen found that the consumption frequency of the previously mentioned edible Solanaceae foods was inversely related to PD risk. In other words, those who consumed more peppers, tomatoes, and potatoes were less likely to develop the disease, even though vegetable intake in general was not associated with PD. The strongest finding was with peppers, which contain the highest dry-weight concentration of nicotine, despite the fact that most individuals consume potatoes and tomatoes more frequently. (For the nicotine levels of several Solanaceae plants, see Table 1.)

“It appears that on a dry-weight basis nicotine is more concentrated in peppers than tomatoes or potatoes, but in absolute terms of nicotine consumption, peppers are likely less important, so it calls into question whether nicotine is important, or rather that something else in both tobacco and peppers is relevant,” said Dr. Searles Nielsen. “Other possibilities are that perhaps concentration is more important than absolute amount, or that we were not able to assess tomato and potato intake as well as we did peppers, since tomatoes and potatoes are in so many foods.”

Due to the relatively small amount of nicotine in edible Solanaceae foods compared with tobacco products, Dr. Searles Nielsen and colleagues also took into account participants’ previous tobacco usage. Importantly, the risk reduction was found mostly in those who were non-smokers.

“Because the amount of nicotine in tobacco likely would overwhelm the relatively tiny amount in the diet, we knew it would be important to consider tobacco use in our analysis,” said Dr. Searles Nielsen. “The observation that the PD-Solanaceae association was mostly confined to individuals who never used tobacco or did so for a short period of time adds strength to our findings. That’s because if the association is real and due to nicotine or something else in Solanaceae, then we would expect that we could best observe it in the people who were not also getting that outside of their diet.”

Dr. Quik, who was not involved in the study but has previously investigated the potential neuroprotective effect of nicotine for PD,4 said she was impressed, but somewhat surprised, by the findings.

“It does seem like a small amount, but then it is potentially over a long period of time, meaning you might start eating your potatoes and tomatoes and peppers starting at the age of one,” Dr. Quik said. “So you might be continually exposed to very small quantities of nicotine your entire life, including later on when Parkinson’s degeneration starts happening in your 30s, 40s, or 50s — no one is quite clear. So even a small amount potentially could be beneficial…. A lifetime of exposure [could make a difference].”

Conclusions and Future Research

Although increased consumption of peppers (and to a lesser extent, tomatoes) was associated with a reduced risk reduction of PD, Dr. Searles Nielsen recommended caution when interpreting the findings.

“This was a well-constructed study and carefully-designed analysis, but as with any study and analysis, questions remain, and it is just one study. Generally, scientists like to see multiple studies with similar findings,” she said. “The study was only designed to better understand what might cause or might prevent Parkinson’s disease. It is not possible for us to examine whether eating peppers or other Solanaceae foods is beneficial to people who already have the disease (e.g., slow its progression), although that would be a potentially important line of research if the findings we report are replicated.”

Dr. Quik mentioned one particular limitation of the study — the fact that environmental, or second-hand, tobacco smoke was not taken into consideration. “In the past a lot of us were exposed to smoking from relatives all day long. Smoking was everywhere, and it really wasn’t that long ago. So the second-hand smoke question is an important one.”

This limitation was recognized in Dr. Searles Nielsen’s paper, although findings from a small group of cases and controls with data on environmental tobacco smoke were not affected by taking this factor into account. Further, because of the “retrospective” study design, it is difficult to rule out that the disease might have affected dietary choices even before diagnosis. In the paper, Dr. Searles Nielsen recommended epidemiological studies “designed to address these limitations,” which “may shed further light on our somewhat novel hypothesis and findings.”

One peer reviewer of this article questioned the relationship between edible nicotine from Solanaceae foods and PD risk reduction, based on the relative amounts of nicotine in foods compared to cigarette smoking. “The absorption of nicotine after smoking one cigarette is estimated as 1 mg,” said Ethan Russo, MD, a senior medical advisor at GW Pharmaceuticals. “In contrast, the nicotine content of peppers, potatoes, tomatoes and eggplant is a tiny fraction of this.”

Dr. Russo suggested that something else — perhaps bioflavonoids (“those rich pigments in the vegetables … that scavenge free radicals that lead to cell damage and neuronal wastage over time”) — in Solanaceae foods might be responsible for the beneficial effects seen in the study. However, since the study was designed to look at only nicotine, more research would be needed to assess what, if any, effects other biochemicals could have in a similar study.

Dr. Quik noted that only when a combination of studies — animal, laboratory, epidemiological, and others — start to point to a similar conclusion, that scientists and consumers can feel more confident about the association of nicotine consumption — dietary, or otherwise — and PD risk reduction.

“It’s certainly a very interesting possibility that nicotine might be neuroprotective. When you put it all together, and you come to a potential conclusion that nicotine might be a component, not necessarily the only component, that could be useful [in PD risk reduction],” said Dr. Quik. “I think you need [multiple types of studies], and when they all converge, that’s wonderful.”

—Tyler Smith

References

1. Searles Nielsen S, Franklin GM, Longstreth WT, Jr., Swanson PD, Checkoway H. Nicotine from edible Solanaceae and risk of Parkinson disease. Annals of Neurology. 2013. DOI: 10.1002/ana.23884. Available here. Accessed May 15, 2013.

2. Understanding Parkinson’s disease. Parkinson’s Disease Foundation website. Available here. Accessed May 21, 2013.

3. Smoking and tobacco use. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website. Available here. Accessed May 24, 2013.

4. Quik M, Perez XA, Bordia T. Nicotine as a potential neuroprotective agent for Parkinson’s disease. Movement Disorders. 2012. DOI: 10.1002/mds.25028. Available here. Accessed May 15, 2013.

|