|

Editor’s Note: Each month, HerbalEGram highlights a conventional

food and briefly explores its history, traditional uses, nutritional profile,

and modern medicinal research. We also feature a nutritious recipe for an

easy-to-prepare dish with each article to encourage readers to experience the

extensive benefits of these whole foods. With this series, we hope our readers

will gain a new appreciation for the foods they see at the supermarket and

frequently include in their diets.

The basic materials for

this series were compiled by dietetic interns from Texas State University in

San Marcos and the University of Texas at Austin through the American Botanical

Council’s (ABC’s) Dietetic Internship Program, led by ABC Education Coordinator

Jenny Perez.

We would like to acknowledge Perez, ABC Special Projects Director Gayle Engels,

and ABC Chief Science Officer Stefan Gafner, PhD, for their contributions to

this project.

By Hannah Baumana and Mindy Greenba HerbalGram Assistant Editor b ABC Dietetics Intern (UT, 2014)

History

and Traditional Use

Range and Habitat

Vitis vinifera means “the vine that bears

wine” and belongs to the Vitaceae family. Grapes are perennial climbers that

have coiled tendrils and large leaves. They contain clusters of flowers that mature

to produce small, round, and juicy berries that can be either green (“white”)

or red.1 There are seed and seedless varieties, although the seeds

are edible and packed with nutrition. The juice, pulp, skin, and seed of the

grape can be used for various preparations.2

Grapes are a vine and

must be trained to grow along a fence, wall, or arbor.3 The fruit

does not ripen after harvesting; therefore, it is important to harvest

well-colored and plump berries that are wrinkle-free and still firmly attached

to the vine. They are best stored in the refrigerator since freezing will

decrease their flavor.1,4 Pesticide use is common in vineyards, and

careful washing is recommended when purchasing conventionally grown grapes. .jpeg)

As one of the leading commercial fruit crops

in the world in terms of tons produced, grapes are cultivated all over the

world in temperate regions. The top producers are Italy, France, Spain, the United

States, Mexico, and Chile.1,5 Annually, worldwide grape production

reaches an average of 60 million metric tons, 5.2 million of which are grown in

the United States.

Phytochemicals

and Constituents

Antioxidants are enzymes and nutrients that

prevent oxidation, meaning they neutralize highly reactive ions or molecules known

as free radicals in the human body by donating electrons, or modulating enzymes

that metabolize free radicals. Free radicals are produced naturally through

metabolism as part of normal physiological functions (e.g., a defense mechanism

against pathogens), but may be produced in excess, creating a situation where they adversely alter lipids, proteins, and DNA, and trigger a

number of human diseases. Grape and grape products are

good sources of beneficial antioxidant compounds.

Grapes contain phytochemicals called

polyphenols. Polyphenols are the most abundant source of dietary antioxidants

and are associated with numerous health benefits.2,6 The phenolic

compounds are more concentrated in the skin of the berry, rather than in the

flesh or seeds, and the content tends to

increase as the fruit ripens. Grapes contain polyphenols from the classes of flavonoids,

stilbenes, and phenolic acids. Red wine and grapes are rich in flavonoids such

as anthocyanins and catechins, stilbenes such as resveratrol, and phenolic

acids such as caffeic acid and coumaric acid. Red grapes have higher

concentrations of these phenolic compounds than red wine grapes. Different

grape varietals contain varying amounts of phenolic compounds.

Anthocyanins are flavonoids that naturally

occur in the plant kingdom and give many plants their red, purple, or blue pigmentation.

Vitis vinifera may contain up to 17 anthocyanin pigments, which are

contained in the skins.2,7 Grapes also contain other flavonoids,

including catechins, epicatechins, and proanthocyanidins. Attempts to study the

benefits of individual phytochemicals in humans has been difficult since these

phytochemicals are complex and often interact with one another to increase

their overall benefits.

There are numerous studies using animal

models in phytochemical research.8 Animal models have shown that

anthocyanins protect against oxidative stress, which can be the beginning

stages of many chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes,

and cancer.

Grape

seeds are a particularly rich source of proanthocyanidins, a class of nutrients belonging to the flavonoid family. Proanthocyanidins,

also known as condensed tannins, are polymers (naturally occurring large

molecules) with flavan-3-ol monomers as building blocks. The term oligomeric proanthocyanidin (OPC), which

also is commonly used to describe these compounds, is not well-defined and is debated

among various members of the scientific community.

Grape seed

extract is available as a nutritional supplement. Partially purified

proanthocyanidins have been used in phytomedicinal preparations in Europe for

their purported activity in decreasing the fragility and permeability of the

blood vessels outside the heart and brain.9

Grapes have a high stilbene, specifically

resveratrol, content. Resveratrol, which is found in the skin and seeds of red

grapes as well as in red wine, is produced as the plant’s defense mechanism

against environmental stressors.1,2,10,11 Resveratrol first gained

attention as a possible explanation for the “French Paradox” — the observation

that French people tend to have a low incidence of heart disease despite having

a typically high-fat diet.1 The antioxidant activity of grapes is

strongly correlated with the amount of resveratrol found in the grape.10

Studies have found resveratrol to be anti-carcinogenic, anti-inflammatory, and

cardio-protective in animal models.11 However, in a human study in

which healthy adults consumed resveratrol, it was determined that the compound was

readily absorbed, but it metabolized quickly, leaving only trace amounts.12

In addition to their high resveratrol

content, grapes are also an excellent source of vitamin K and provide moderate

amounts of potassium, vitamin C, and B vitamins.

Historical and

Commercial Uses

Grapes have been consumed since prehistoric

times and were one of the earliest domesticated fruit crops.1,13 According

to ancient Mediterranean culture, the “vine sprang from the blood of humans who

had fought against the gods.”14 But according to archaeological

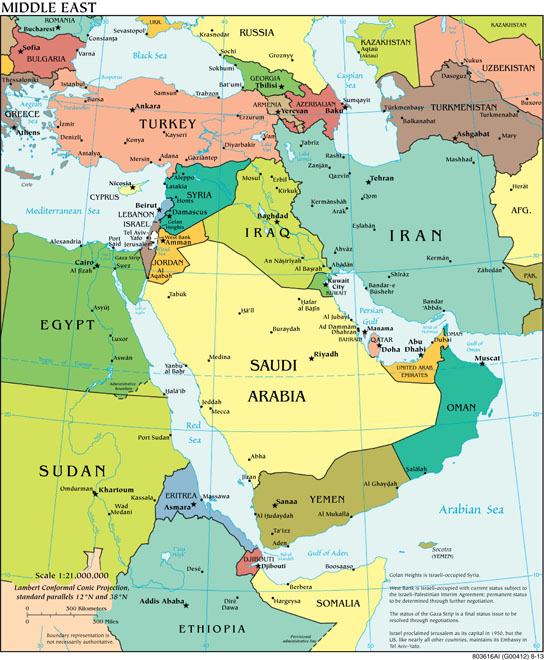

evidence, domestication took place about 5,000 years ago somewhere between the

Caspian and Black Seas, and spread south to modern-day Syria, Iraq, Jordan, and

Egypt before moving towards Europe.5,13 After the collapse of the

Roman Empire in the 5th century, when Christianity became dominant, wine was

associated with the Church and the monasteries soon perfected the process of

making wine.1

About 300 years ago, Spanish explorers

introduced the grape to what is now the United States, and California’s

temperate climate proved to be an ideal place for grape cultivation.1

The grape is, famously, the most common

ingredient in wine-making. A naturally-occurring symbiotic yeast grows on the

grapes, making them easier to ferment and well-suited to the wine-making

process.4 Popular wine cultivars of V. vinifera include Cabernet Sauvignon, Merlot, Chardonnay,

Sauvignon Blanc, Vermentino, and Viognier.10

Wine often has been used as a medium for

herbal remedies, due to the solvent nature of the alcohol. Both the Chinese and

Western traditions made use of medicated wines (though ancient recipes in China,

which date to the Shang Dynasty [ca 1600-1046 BCE], would have been made with

rice [Oryza sativa, Poaceae] wine

rather than grape wine).15 Many aperitifs and liqueurs originally

were digestive aids made with wine and fortified with herbs such as wormwood (Artemisia absinthium, Asteraceae) and

anise seed (Pimpinella anisum,

Apiaceae).16 Medicated wines are less potent and usually require a

higher dosage than tinctures made with higher-proof alcohol.

Grapes are generally sweet and are used as

table grapes, juice, jam, jelly, or for wine-making.13,17 About 99%

of the world’s wine comes from V. vinifera.14

Grapes can also be dried in the vineyard

and turned into raisins. To accomplish this, ripe grapes are plucked from the

vine and placed on paper trays for two to four weeks. Afterwards, they are sent

to the processing plant to be cleaned, packaged, and shipped.5

Modern Research

Grapes have been the subject of numerous

studies focused on many of their bioactive compounds, including flavonoids,

stilbenes, and phenolic acids. Researchers have observed antioxidant, anti-tumor,

immune modulatory, anti-diabetic, anti-atherogenic, anti-infectious, and

neuro-protective properties of the fruit.11 Research suggests that

grape product consumption could possibly benefit those with cancer, diabetes,

and cardiovascular disease, which are among the leading causes of death worldwide.18

However, more human studies are needed to support any of these purported

benefits.

An in vitro study showed that antioxidants

from a variety of grape product extracts performed as well as or better than

BHT, tocopherol, and trolox in radical scavenging activity, metal chelating

activity, and inhibition of lipid peroxidation.7 Water and ethanol

seed extracts had the highest amount of phenolic compounds of any of the

extracts used in the study.

Grape seed extract (GSE), which has a

growing body of study behind it, has gained attention for its possible use in

lowering blood pressure and reducing the risk of heart disease, especially in

pre-hypertensive populations.19 Unlike grape skins, where only red

grapes contain anthocyanins, seeds from both white and red grape contain

beneficial compounds. A standardized GSE made from white wine grapes recently

was studied for its effects on gastrointestinal inflammation.20

While most studies focus on GSE and cardiovascular health, the preliminary

results were promising enough to warrant a future human trial.

Cardiovascular Disease

Polyphenols have been found to protect the

body from inflammation, which is common in people with heart disease.11

In a recent meta-analysis, the acute effects of polyphenols on the endothelium

(inner lining of the blood vessels) were investigated. The analysis found that

blood vessel function significantly improved in healthy adults in the initial

two hours after consuming grape polyphenols.21 Another analysis

found that the polyphenol content in every part of the grape — fruit, skin, and

seed — had cardioprotective effects.22 In animal, in vitro, and

limited human trials, grapes showed beneficial actions against oxidative stress,

atherosclerosis (plaque build-up in arteries), high blood pressure, and

ventricular arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

Cancer Chemopreventive Effects

Although the causes of and treatments for

cancer are complex and multifaceted, studies have been done on the antioxidant

activity of polyphenols and their cancer chemopreventive effects. These

antioxidants demonstrate the ability to protect the body from cancer-causing

substances and to prevent tumor cell growth by protecting DNA and regulating

natural cell death.8,11,23

Diabetes

In a randomized, double-blind controlled clinical

study, healthy overweight/obese first degree relatives to type 2 diabetic

patients were given grape polyphenols to counteract a high-fructose diet. After

nine weeks of supplementation, grape polyphenols protected against

fructose-induced insulin resistance.24 In another study, diabetic

patients who consumed a dealcoholized Muscadine grape wine had reduced fasting

insulin levels and increased insulin resistance.25

Nutrient

Profile26

Macronutrient Profile: (Per 150 g

[approx. 1 cup] grapes)

104 calories

1.1 g protein

27.3 g carbohydrate

0.2 g fat

Secondary Metabolites: (Per 150 g

[approx. 1 cup] grapes)

Excellent source of:

Vitamin K: 22 mcg

(27.5% DV)

Good source of:

Potassium: 288 mg

(8.2% DV)

Vitamin C: 4.8 mg

(8% DV)

Thiamin: 0.1 mg

(6.7% DV)

Riboflavin: 0.1

mg (5.9% DV)

Dietary Fiber: 1.4

g (5.6% DV)

Manganese: 0.1 mg

(5.5% DV)

Vitamin B6: 0.1

mg (5% DV)

Also provides:

Phosphorus: 30 mg

(3% DV)

Magnesium: 11 mg

(2.8% DV)

Iron: 0.5 mg

(2.8% DV)

Vitamin A: 100 IU

(2% DV)

Niacin: 0.3 mg

(1.5% DV)

Vitamin E: 0.3 mg

(1.5% DV)

DV = Daily Value as established by the US Food and Drug Administration,

based on a 2,000-calorie diet.

Recipe: Rosemary-Roasted

Grapes and Cashew Cheese Crostini

Ingredients:

- 1 cup raw cashews

- 1-2 cloves of

garlic, minced

- 1/4 cup water

- 1/4 cup freshly-squeezed

lemon juice, divided

- 1/2 teaspoon kosher

or fine sea salt

- 1 pound seedless

red grapes, washed and removed from stem

- 3 tablespoons

olive oil, plus more for garnish

- 1 tablespoon fresh

rosemary leaves, minced

- Salt and pepper

to taste

- 1 small baguette

or other loaf, sliced diagonally in 1/4 inch thick slices

Directions:

- Soak cashews in enough water to cover by an inch for at least 4 hours.

Drain.

- Make cashew “cheese” by placing soaked cashews, garlic, water, 2

tablespoons of lemon juice, and salt into a food processor and blend until

smooth.

- Heat oven to 400°F. In a baking dish, mix grapes, olive oil, remaining

lemon juice, rosemary, salt, and pepper. Place on center rack and roast 10-12 minutes

or until skins are soft. Remove and set aside.

- Move the oven rack to the top setting and increase the heat to broil. Arrange

bread slices in a single layer on a baking sheet and place in oven to toast for

1-3 minutes, monitoring carefully to prevent burning.

- Assemble crostini by spreading each toast with a layer of cashew

cheese and topping with the grape mixture. Sprinkle with salt and drizzle with

olive oil. Serve warm.

References

1. Murray MT,

Pizzorno J, Pizzorno L. The Encyclopedia

of Healing Foods. New York, NY: Atria Books; 2005.

2. Yang

J, Xiao YY. Grape phytochemcials and associated health benefits. Critical

Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition.

2013;53:1202-1225.

3. Damrosch

B. Grapes. In: The Garden Primer: Second Edition. New York, NY: Workman

Publishing; 2008:353-359.

4. Wood

R. The New Whole Foods Encyclopedia: A

Comprehensive Resource for Healthy Eating. New York, NY: Penguin Books;

1999.

5. Ensminger

AH, Ensminger ME, Konlande JE. The

Concise Encyclopedia of Foods & Nutrition. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press;

1995.

6. Tiwari

B, Brunton NP, Brennan CS. Handbook of

Plant Food Phytochemicals. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2013.

7. Keser S, Celik S,

and Turkoglu S. Total phenolic contents and free-radical scavenging activities

of grape (Vitis vinifera L.) and grape products. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition.

2013;64(2):210-216.

8. Lila

MA. Anthocyanins and human health: An in vitro investigative approach. J

Biomed Biotechnol. 2004;2004(5):306-313.

9. Yamakoshi J, Saito M, Kataoka S, Kikuchi M. Safety evaluation of

proanthocyanidin-rich extract from grape seeds. Food and Chemical Toxicology.

2002;40:599-607.

10. Burin

VM, Ferreira-Lima NE, Panceri CP, Bordignon-Luiz MT. Bioactive compounds and

antioxidant activity of Vitis vinifera

and Vitis labrusca grapes: Evaluation

of different extraction methods. Microchemical Journal. 2014;114:155-163.

11. Yadav

M, Jain S, Bhardwaj A, et al. Biological and medicinal properties of grapes and

their bioactive constituents: An update. Journal of Medinical Food. 2009;12(3):473-484.

12. Walle

T, Hsieh F, DeLegge MH, Oatis JE, Walle K. High absorption but very low

bioavailability of oral resveratrol in humans. Drug Metabolism and

Disposition. 2004;32(12):1377-1382.

13. Myles

S, Boyko AR, Owens CL, et al. Genetic structure and domestication history of

the grape. Proceedings of the National Academy of Science of the United

States of America. 2011;108(9):3530-3535.

14. McGovern

PE. Ancient Wine: The Search for the

Origins of Viniculture. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 2007.

15. Chan K, Cheung L.

Interactions Between Chinese Herbal

Medicinal Products and Orthodox Drugs. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2000.

16. Hoffmann D. The Herbal Handbook: A User’s Guide to

Medical Herbalism. Rochester, VT: Inner Traditions; 1998.

17. Onstad

D. Whole Foods Companion: A Guide for

Adventurous Cooks, Curious Shoppers, and Lovers of Natural Foods. White

River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing; 2004.

18. The top 10 causes

of death – fact sheet no. 310. World Health Organization website. May 2014.

Available here.

Accessed November 23, 2015.

19. Park E,

Edirisinghe I, Choy YY, Waterhouse A, Burton-Freeman B. Effects of grape seed

extract beverage on blood pressure and metabolic indices in individuals with

pre-hypertension: a randomised, double-blinded, two-arm, parallel,

placebo-controlled trial. Br J Nutr.

2015;16:1-13.

20. Starling S. White

wine extract shows gastro benefits in vitro. Clinicals planned for 2016.

NutraIngredients-USA website. November 12, 2015. Available here.

Accessed November 19, 2015.

21. Li

SH, Tian HB, Zhao HJ, Chen LH, Cui LQ. The acute effects of grape polyphenols

supplementation on endothelial function in adults. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(7):e69818.

22. Leifert WR,

Abeywardena MY. Cardioprotective actions of grape polyphenols. Nutrition Research. 2008;28:729-737.

23. Waffo-Téguo P,

Hawthorne ME, Cuendet M, et al. Potential cancer-chemopreventive activities of wine

stilbenoids and flavans extracted from grape (Vitis vinifera) cell cultures. Nutrition

and Cancer. 2001;40(2):173-179.

24. Hokayem

M. Grape polyphenols prevent fructose-induced oxidative stress and insulin

resistance in first-degree relatives of type 2 diabetic patients. Diabetes

Care. 2013;36:1455-1461.

25. Banini AE, Boyd

LG, Allen JG, Allen HG, Sauls DL. Muscadine grape products intake, diet and

blood constituents of non-diabetic and type 2 diabetic subjects. Nutrition. 2006;22:1137-45. 26. Basic Report: 09132, Grapes, red or green

(European type, such as Thompson seedless), raw. United States Department of

Agriculture, Agricultural Research Service. Available here. Accessed November

19, 2015. |