Editor’s Note: Each month, HerbalEGram highlights a conventional food and

briefly explores its history, traditional uses, nutritional profile, and modern

medicinal research. With each article, we also feature a nutritious recipe for

an easy-to-prepare dish to encourage readers to experience the extensive

benefits of these whole foods. With this series, we hope our readers will gain

a new appreciation for the foods they see at the supermarket and frequently

include in their diets.

The basic materials for this series were compiled

through the American Botanical Council’s (ABC’s) Dietetic Internship Program. We would like to acknowledge ABC Chief Science Officer

Stefan Gafner, PhD, for his contributions to this project.

By Hannah

Baumana and Jenny Perezb

a HerbalGram Associate Editor

b ABC Education

Coordinator

Overview

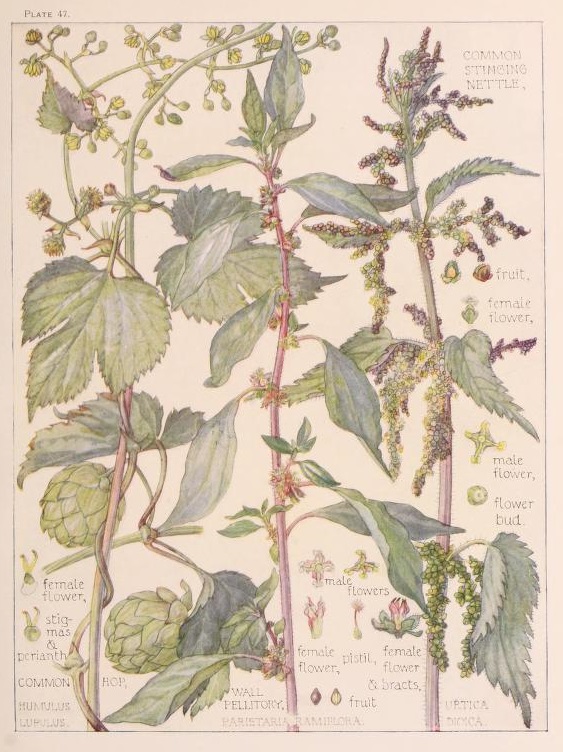

Urtica dioica (Urticaceae) is

commonly known as nettle, common nettle, or stinging nettle. The species is an

herbaceous perennial with a spreading growth habit. Growing 4-6 feet tall,

stinging nettle produces numerous erect and wiry stems that hold up its

opposite, roughly textured, serrated leaves.1-4 It produces small,

inconspicuous greenish-brownish flowers that emerge as axillary inflorescences.2

The stems and  undersides of leaves are covered with hairs called

trichomes. When touched, these stinging trichomes inject a chemical cocktail

that typically causes localized skin irritation as well as a painful, tingling

sting from which the species has derived its most common name, stinging nettle.1,5 undersides of leaves are covered with hairs called

trichomes. When touched, these stinging trichomes inject a chemical cocktail

that typically causes localized skin irritation as well as a painful, tingling

sting from which the species has derived its most common name, stinging nettle.1,5

The

Urticaceae family contains about 500 known species, distributed mainly in tropical

areas.1 The genus Urtica, whose

name comes from the Latin uro (to

burn) and urere (to sting), consists

of both annual and perennial herbaceous plants known for the burning properties

of the stinging hairs of their leaves and stems.1,2,6 (Nettle

is the Anglo-Saxon word for “needle.”) Urtica

urentissima, a species found in Java, produces burning effects that can

last an entire year and reportedly can even cause death. Urtica dioica is, comparatively, a more docile species that has a

long history of use as a food and medicine.1,2,7 It is widely

distributed in temperate climates of Europe, Asia, northern Africa, and North

America.1 In North America, U.

dioica has become naturalized in every state except Hawaii.1 There

are at least six subspecies of U. dioica,

some of which formerly were classified as separate Urtica species. Urtica dioica

subsp. galeopsifolia is the only one

of the six subspecies that does not have stinging hairs.1

Phytochemicals and Constituents

Stinging

nettle is a perennial edible whose leaves are a relatively good source of

caloric energy, protein, fiber, and an array of health-promoting bioactive

compounds.7 These include vitamins A, C, and K; fatty acids

(α-linoleic acid and linoleic acid); and minerals including iron, manganese,

potassium, and calcium.2,7,8 Notably, stinging nettle leaves contain

nine carotenoids, including lutein and lutein isomers, β-carotene, and

β-carotene isomers.2 Other phytochemicals in nettle leaf include B

vitamins, vitamin E, coumarins, flavonoids, phenolic acids, tannins, organic

acids, water-soluble silicates, and chlorophyll.8,9 The therapeutic

benefit of stinging nettle is attributed to its abundant phenolic compound

content, which includes caffeic acid, ferulic acid, esculetin, scopoletin, kaempferol,

quercetin, quercitrin, rutin, and glycoproteins.2 Stinging nettle

leaves can be cooked like spinach (Spinacia

oleracea, Chenopodiaceae) and are safe for consumption, as heat deactivates

the stinging compounds.10 Nettle leaf has higher levels of all

essential amino acids, except leucine and lysine, than spinach.11

When

harvested at a length of four to six inches, young nettle leaves are most

tender, sting less, and are higher in iron and manganese than mature leaves.5

However, nettle plants that are two years old or more contain higher levels of

chlorophyll and carotenoids than younger plants. Young leaves harvested in

early spring also can be dried for use in teas, soups, and baked goods. Nettle

leaf retains a significant portion of vitamins, minerals, and essential nutrients

even after leaves are blanched or cooked/boiled prior to freezer storage. To

prepare a nettle infusion that retains the highest level of vitamin C, a study

confirmed that the most efficient steeping time is 10 minutes at a temperature

of 140°F (60°C).8 Further consideration should be given to the

processing and selling of stinging nettle leaf as a functional and nutritive

food.

Historical and Commercial Uses

Some

consider stinging nettle a bothersome weed, but its long history of use tells a

different story. Stinging nettle has been used as a source of fiber (stem), dye

(leaf and rhizome), food/fodder (leaf), and medicine (leaf, rhizome/root, and

seed).2,8

Since

ancient times, stinging nettle has been used as a fiber crop substitute for

flax (Linum usitatissimum, Linaceae).

In Denmark, burial shrouds made from nettle fiber were discovered that date

back to the Bronze Age (3000–2000 BCE). Early Europeans and indigenous

Americans used the strong nettle fiber to make sailcloth, sackcloth,

cordage/rope, and fishing nets.1 In Scotland, nettle stalk was

cultivated for fiber and also used for small-scale papermaking. Nettle fiber

also was used during both World Wars when other crops like cotton (Gossypium hirsutum, Malvaceae) were scarce.

Stinging nettle fiber has a cellulose content similar to that of flax and hemp

(Cannabis spp., Cannabaceae), and it

is much stronger than both flax and cotton, while being comparable in strength

to ramie (Boehmeria nivea,

Urticaceae) fiber.12

In

periods of food shortage during both World Wars, stinging nettle was used

fresh, dried, milled, or as silage for feeding poultry, cattle, horses, and

pigs.12 Ranchers used nettle in livestock feed as a nutritious way

to supplement the animals’ diets. By adding stinging nettle leaf into poultry

feed, vitamin A intake increased by about 60-70% and protein intake by about 15-20%,

reducing overall feeding requirements by about 30%. Hens supplemented with

nettle feed typically lay eggs with brighter yellow carotenoid-rich yolks.12

Considered

a nutritive food and medicine for thousands of years among numerous cultures,

stinging nettle  leaves have been used traditionally for scurvy, anemia,

arthritis, seasonal allergies, wound healing, and general fatigue, and as a

diuretic and to stimulate pancreatic secretion.1,9 Stinging nettle

tea has been used historically as a cleansing spring tonic and blood purifier.1,3

The juice of nettle leaf has been used as a hair rinse to control dandruff and

to stimulate hair growth, and is a functional ingredient in modern European

hair-care formulations. It is used as a vegetarian source of rennet in

cheese-making and is still included among Passover herbs.1 leaves have been used traditionally for scurvy, anemia,

arthritis, seasonal allergies, wound healing, and general fatigue, and as a

diuretic and to stimulate pancreatic secretion.1,9 Stinging nettle

tea has been used historically as a cleansing spring tonic and blood purifier.1,3

The juice of nettle leaf has been used as a hair rinse to control dandruff and

to stimulate hair growth, and is a functional ingredient in modern European

hair-care formulations. It is used as a vegetarian source of rennet in

cheese-making and is still included among Passover herbs.1

Nettle

leaf has been used safely in large food-like doses (up to 100g daily) for

thousands of years.5 Ancient Egyptians reportedly used nettle

infusions to relieve arthritis and lower back pain.7 Hippocrates

(460-ca. 377 BCE) and other early Greek physicians used nettle for more than 60

ailments. In the first and second centuries CE, Greek physicians Dioscorides

and Galen reported the use of stinging nettle leaf for its diuretic and

laxative properties and for the treatment of asthma, pleurisy, and spleen

illnesses.3 The 16th-century herbalist John Gerard used nettle leaf

as an antidote for poison.1 In the 19th century, the classification

of stinging nettle as a diuretic was documented in Greek medical literature.5

It is

thought that nettle leaf’s high chlorophyll content gives it detoxifying and anti-infective

properties. In his 2nd-century book De

Simplicibus Medicaminibus, Galen

recommended nettle for dog bites, gangrenous wounds, swellings, nosebleeds,

mouth sores, and tinea (fungal infections caused by ringworm). Seventeenth-century

English herbalist Nicholas Culpeper recommended a nettle-honey preparation for wounds

and skin infections, worms in children, as an antidote to venomous stings, and as

a gargle for throat and mouth infections.1 Modern research on

chlorophyll indicates that it has some detoxifying, anti-carcinogenic

properties and may ameliorate the side effects of some drugs.2 Nettle

leaves also are used as a source of chlorophyll for commercial supplements.13

Additionally, nettle’s vitamin K-rich leaves were powdered and used as a

styptic for nosebleeds, and used internally for excessive menstruation, and

internal bleeding.1,3

The

season for nettle leaf medicine is spring, when it traditionally is harvested

and used fresh or dried for its ability to deliver bountiful nutrients.1

Many North American tribes consider nettle tea safe and appropriate to use as a

gynecological aid for those with anemia or malnourishment.1

Stinging

nettle is a very popular wild edible plant (WEP) in several developing

countries, where it is used in soups, curries, or as a cooked vegetable. Vinegar

or lemon (Citrus limon, Rutaceae) juice often is added to cooked nettle

preparations to improve flavor and enhance mineral absorption.14 In the

Caucasus country of Georgia, a meal of boiled nettle greens seasoned with

walnuts (Juglans spp., Juglandaceae) is

common. In many cases, these WEPs contribute to community food security and,

potentially, to local economies.7

Nettle

leaf powder/flour has been incorporated into breads and pastas and is used as a

protein-rich supplement in starchy diets. In one analysis, the protein content

of ground wheat (Triticum aestivum,

Poaceae), barley (Hordeum vulgare,

Poaceae), and stinging nettle was found to be 10.6%, 11.8%, and 33.8%,

respectively, indicating that the nettle powder contained about three times more

protein per serving than the cereal crops. 7

A low-carbohydrate,

high-fiber diet can support good digestive health. Nettle powder has low

carbohydrate content with high levels of protein, minerals, fat, and fiber.

Nettle powder is considered a low-glycemic food. Whole grains alone can provide

much needed fiber to the diet. However, grain products enriched with nettle

powder can provide extra fiber, in addition to an array of healthful nutrients.

When combining nettle powder with barley flour into items like biscuits,

noodles, and breakfast cereals, the protein, mineral, fiber, and bioactive

compound content increased while overall caloric value decreased, according to

an analysis. 7

A practice

called “urtification” is perhaps the most ancient medicinal use of the plant. In

this process, fresh nettle, with its stinging compounds, was applied externally

as a rubefacient to stimulate circulation and bring warmth to joints and

extremities of paralytic, rheumatic, or stiff limbs.5,7 This induced,

localized irritation stimulates an immune response and pain relief after the

stinging subsides. This was considered standard practice for treating chronic

rheumatism, lethargy, coma, paralysis, and even typhus and cholera.1,5

Ironically, nettle leaves often were prepared as syrup or tincture to treat

urticaria, or the rash they produce upon contact with the skin.1

The

root of stinging nettle is a rich source of phytosterols and has been used to

reduce prostate gland inflammation and to treat rheumatic gout, nettle rash,

and chickenpox.3,10 In 1986, the German Commission E approved the

use of stinging nettle root, taken orally, as a nonprescription medicine to

treat urinary difficulties associated with stages I and II of Benign Prostatic

Hyperplasia (BPH).14,15 The European Medicines Agency’s 2012 monograph

on nettle root indicates its safe use to relieve lower urinary tract symptoms

(LUTS) related to BPH.16

Modern Research

Based

on published evidence, U. dioica and

its phytoconstituents have both hypoglycemic and anti-inflammatory activities.3

Nettle leaf, whether used orally or topically, has been shown to be able to inhibit

pro-inflammatory enzymes.2 This indicates that nettle leaf may be a

potential aid in treating chronic, inflammatory disease processes. Promising

evidence suggests that nettle can help control inflammation associated with

diabetes mellitus, rheumatoid and osteoarthritis, allergic rhinitis (hay fever),

and BPH.12

Diabetes Mellitus

Type

2 diabetes mellitus has become one of the most common preventable diseases

globally. Hyperglycemia, the relative or absolute deficiency of insulin at the

cellular level, is one of the predisposing factors for oxidative stress in the

body.17 Oxidative stress — often indicated by elevated levels of low-density  lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT), and low levels

of nitric oxide — increases the incidence of cardiovascular risk factors and

contributes to diabetic macro- and micro-vascular complications. Moreover, high

blood glucose causes fat deposits in the liver. Stinging nettle leaf extracts have demonstrated natriuretic

(stimulating sodium excretion via urine), diuretic, and hypotensive effects.

Nettle leaf offers a therapeutic dietary option for patients with digestive and

kidney diseases or injuries after renal transplantation, as well as those with

diabetes.2 lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol and glutamic pyruvic transaminase (SGPT), and low levels

of nitric oxide — increases the incidence of cardiovascular risk factors and

contributes to diabetic macro- and micro-vascular complications. Moreover, high

blood glucose causes fat deposits in the liver. Stinging nettle leaf extracts have demonstrated natriuretic

(stimulating sodium excretion via urine), diuretic, and hypotensive effects.

Nettle leaf offers a therapeutic dietary option for patients with digestive and

kidney diseases or injuries after renal transplantation, as well as those with

diabetes.2

Stinging

nettle leaf extract acts on the pancreas to increase insulin secretion by the

Islets of Langerhans and has an inhibitory effect on alpha-glucosidase.

Theoretically, stinging nettle leaf extract’s polyphenols may protect beta

cells in the pancreas and stabilize lipid peroxidation.17 Its

effects on blood pressure are tied directly to stinging nettle’s ability to

increase serum nitric oxide levels, which opens potassium channels and has relaxant

effects on blood vessel walls.

A

2015 clinical study found that supplementation with U. dioica hydroethanolic aerial parts extract for eight weeks helped

improve markers of cardiovascular disease and oxidative stress in diabetic

patients.17 At the end of the study, participants in the nettle

extract group experienced a statistically significant reduction in fasting

blood glucose, lower triglyceride levels, increased high-density lipoprotein (HDL)

cholesterol levels, decreased SGPT levels, increased nitric oxide levels, and

increased superoxide dismutase (SOD) over baseline, indicating an overall

reduction in oxidative stress. The only change in the placebo group was an

increase in triglyceride levels. Researchers suggest these results encourage

the use of U. dioica as an additional

therapy in those with type 2 diabetes.

Rheumatoid Arthritis and Osteoarthritis

According

to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the most common

form of arthritis is osteoarthritis. Other common rheumatic conditions include

gout, fibromyalgia, and rheumatoid arthritis.18 In clinical trials

that tested the effectiveness of nettle extract or capsules against the common

NSAID diclofenac for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, and

fibromyalgia, stinging nettle preparations alone provided moderate pain relief and

had fewer side effects than diclofenac.5 The use of stinging nettle

in addition to diclofenac provided the greatest amount of pain relief, and

subjects used lower doses of diclofenac to achieve pain relief.

The

use of fresh nettle topically to control pain and inflammation works in the

same manner as topical capsaicin cream: the histamine released upon contact

causes a counterirritant effect resulting in localized irritation that blocks

afferent sensory nerves from carrying pain signals away from the area of

urtication.5,19 Three different clinical trials have investigated topical

nettle leaf application for the treatment of pain associated with

osteoarthritis. Participants in these trials reported a significant reduction

in pain as well as the use of NSAIDs for pain management.5 Other

studies have investigated pain relief with a cream from a stinging nettle

extract in an oil-in-water emulsion, a more practical way to integrate modified

“urtification” treatment in a clinical setting.19

One

small clinical study with 23 osteoarthritis patients used nettle cream topically

twice daily for two weeks. After the study concluded, not only was there a mean

reduction in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC)

scores for those using the stinging nettle leaf cream, but many of the

participants requested continuance of the nettle cream treatment to alleviate

pain and improve physical function.19

Allergic Rhinitis

Allergic

rhinitis, or seasonal allergies, is a major risk factor for developing asthma.20

Common over-the-counter (OTC) drugs for seasonal allergy symptoms often are

associated with adverse side effects, including drowsiness, dry mouth, and headache.

Freeze-dried stinging nettle leaves have been used to treat symptoms of

allergic rhinitis. Freezing the fresh leaves or their extracts preserves the

bioactive amines including histamine and acetylcholine.5 Nettle leaf

prevents the release of pro-inflammatory mediators that cause allergic symptoms

such as sneezing, nasal congestion, or itchy, watery eyes.2

In a

clinical trial, patients with seasonal allergies received 300 mg of

freeze-dried stinging nettle root extract daily for one week. Subjects in this

trial rated the nettle preparation’s effectiveness higher than placebo and

previous allergy medications.5 However, outcomes of a 2017 clinical

trial using freeze-dried nettle root (a proprietary product commercially known

as Urtidin [Barij Essence Pharmaceutical Co.; Kashan, Iran]) for seasonal

allergy relief showed only a small improvement in the treatment group, who

received Urtidin (one 150-mg tablet given four times daily; 600mg total) in

addition to 10 mg loratadine (a common antihistamine) and nasal saline rinses

over a one-month period.20 Despite the safety profile and low

toxicity associated with the use of freeze-dried nettle root, additional,

higher quality clinical trials are needed to further assess the efficacy of freeze-dried

nettle preparations to relieve symptoms associated with seasonal allergies.

Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia

BPH

is a  common condition that occurs in aging men and eventually leads to LUTS, such

as pain and difficulty with urination, urine storage, and post-urination (post-micturition)

symptoms including dribbling and feeling of incomplete emptying.21 Standard

medical treatments for LUTS include α1-blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors,

but both have undesirable side effects (postural hypotension and sexual

dysfunction, respectively). common condition that occurs in aging men and eventually leads to LUTS, such

as pain and difficulty with urination, urine storage, and post-urination (post-micturition)

symptoms including dribbling and feeling of incomplete emptying.21 Standard

medical treatments for LUTS include α1-blockers and 5α-reductase inhibitors,

but both have undesirable side effects (postural hypotension and sexual

dysfunction, respectively).

There

is growing evidence that stinging nettle root is a safe and effective treatment

for BPH.21 A 2016 meta-analysis of the clinical use of stinging

nettle root extract for LUTS and BPH confirm that daily doses of 300-600 mg of

stinging nettle root were superior to active controls (i.e., α1-blocker and

5α-reductase inhibitor pharmaceutical drugs). No randomized controlled trials evaluated

reported any serious adverse side effects in patients who received stinging

nettle root extract.

Consumer Considerations

The

use of stinging nettle leaf as a vegetable poses some challenges. The main challenge

is urticaria: the immediate burning, stinging sensation upon contact with

nettle leaves, which is followed by a short-lived, blanching rash.4 Those

harvesting fresh nettle leaves must be cautious and avoid direct skin contact

by wearing long sleeves and gloves. Once harvested, leaves should be cooked or

steamed for 10-15 minutes before ingesting to deactivate nettle’s stinging

compounds.14 The mechanism of action behind nettle’s sting is both

biochemical and mechanical. Biochemically, nettle hairs release histamine,

serotonin, acetylcholine, and leukotrienes B4 and C4. Mechanical irritation is

induced when some of the trichomes remain in the skin after contact with the

stems or leaves.4 For fresh nettle rash or stings, a poultice of the

leaves of dock (Rumex spp.,

Polygonaceae), which generally grows near nettle patches, is a traditional

remedy.1

An

additional concern is the plant’s ability to bioaccumulate minerals like

chromium, as well as heavy metals like arsenic and lead.22 Nettle

patches are common on farmlands and orchards where soils may have been treated by

agricultural pollutants, which make them contaminated substrates for plants

like stinging nettle. Studies on stinging nettle leaf grown in contaminated

orchard soils indicated significantly higher concentrations of arsenic and lead

than those harvested from wild stands. Based on these findings, soils need to

be tested for heavy metals and other contaminants prior to commercial

cultivation and production of stinging nettle leaves. This will help to ensure

stinging nettle grown for food and medicine maintains its quality and safety.

Nutrient Profile23

Macronutrient Profile: (Per 1 cup stinging

nettle leaves, blanched [approx. 89 grams])

37 calories

2.4 g

protein

6.7 g

carbohydrate

0.1 g

fat

Secondary Metabolites: (Per 1 cup stinging

nettle leaves, blanched [approx. 89 grams])

Excellent source of:

Vitamin

K: 443.8 mcg (369.8% DV)

Vitamin

C: 243 mg (270% DV)

Vitamin

A: 1790 IU (35.8% DV)

Calcium:

428 mg (32.9% DV)

Manganese:

0.7 mg (30.4% DV)

Dietary

Fiber: 6.1 g (20.3% DV)

Very good source of:

Magnesium:

51 mg (12.1% DV)

Riboflavin:

0.14 mg (10.8% DV)

Iron:

1.5 mg (8.3% DV)

Potassium:

297 mg (6.3% DV)

Vitamin

B6: 0.09 mg (5.3% DV)

Phosphorus:

63 mg (5% DV)

Also provides:

Folate:

14 mcg (3.5% DV)

Niacin:

0.35 mg (2.2% DV)

Trace amounts:

Thiamin:

0.01 mg (0.8% DV)

DV =

Daily Value as established by the US Food and Drug Administration, based on a

2,000-calorie diet.

|

Recipe: Stinging

Nettle Spanakopita

Adapted from Jen

Farr24

Wear gloves while handling raw, fresh

nettle leaves and stems. Wash leaves in cool water, then dry thoroughly.

Check the source website for a photo tutorial on preparing the phyllo

packets.

Ingredients:

- 6

sheets frozen phyllo pastry, thawed

- 2

teaspoons melted butter

- 2

tablespoons extra virgin olive oil

- 2

cloves of garlic, minced

- 1

shallot, finely chopped (to learn more about the benefits of shallot, click here25)

- 8

cups stinging nettle leaves and thin stems

- 1

tablespoon lemon juice

- 6

ounces feta cheese, crumbled

- 1

cup ricotta cheese

- Salt

and pepper to taste

Directions:

- Heat

oil in large skillet over medium heat. Add shallot and garlic and cook,

stirring often, until softened, approximately 1-3 minutes.

- Use

tongs to add nettle leaves to skillet in batches, adding more as each

addition cooks down and wilts. Add lemon juice, salt, and pepper and stir to

combine. The nettles are now safe to eat and handle.

- Transfer

the nettle mixture to a cutting board and chop finely with a sharp knife. In

a large bowl, combine the nettle mixture, cheeses, and more salt and pepper

as needed.

- Heat

oven to 350°F. While working with phyllo, prepare one sheet at a time and

keep the rest underneath a damp paper towel to stay cool and workable. Lay

one piece of phyllo pastry on a cutting board and brush with melted butter.

Lay a second piece of pastry on top, then cut the pastry sheet into thirds,

resulting in three long rectangles of pastry.

- Arrange

the first rectangle with the short end toward you, then place one tablespoon

of filling onto the end. Fold a corner up and to the left, covering the

filling and creating a small triangle. Continue triangle-folding the entire

length of the pastry.

- Brush

the outside of the completed triangle-shaped pocket with more melted butter

and set on a parchment paper-lined baking sheet. Continue creating pockets

until all the filling and pastry has been used.

- Bake

spanakopita for 15-20 minutes, or until golden brown and warmed through. Let

rest for five minutes before serving.

|

Image credits (top to bottom): Stinging nettle leaves ©2018 Steven Foster

Stinging nettle patch ©2018 Steven Foster

Botanical illustration from 'Wildflowers of the British Isles' Vol. II by Harriet Isabelle Adams; 1910

Stinging nettle root ©2018 Steven Foster References

- Joshi

N, Pandey ST. Stinging nettle (Urtica

dioica) – history and its medicinal uses. Asian Agri-History. 2007; 21(2):133-138.

- Jan

KN, Zarafshan K, Sing S. Stinging nettle (Urtica

dioica,L.): a reservoir of nutrition and bioactive compounds with great

functional potential. Food Measure. 2017;

11:423-433.

- Ahmed

M, Parsuraman. Urtica dioica,

(Urticaceae): A stinging nettle. Sys Rev

Pharm.2014;5(1):6-8.

- Baumgardner

D. Stinging nettle: the bad, the good, the unknown. Journal of Patient-Centered Research and Reviews. 2016;3(1):48-53.

- Upton

R. Stinging nettles leaf (Urtica dioica

L.): Extraordinary vegetable medicine. Journal

of Herbal Medicine. 2013;3: 9-38.

- Joshi

BC, Mukhija M, Kalia AN. Pharmacognostical review of Urtica dioica L.

International Journal of Green Pharmacy. 2014;201-209.

- Adhikari

BM, Bajracharya A, Shrestha AK. Comparison of nutritional properties of stinging

nettle (Urtica dioica) flour with

wheat and barley flours. Food Science

& Nutrition. 2016; 4(1):119-124.

- Wolska

J, Czop M, Jakubczyk k, Janda K. Influence of temperature and brewing time of

nettle (Urtica dioica, L.) infusions

on vitamin C content. Rocz Panstw Zakl

Hig. 2016;67(4):367-371.

- Lichius JJ, Hiller K, Loew D.

Urticae folium, Urticae herba. In: Blaschek W, ed. Wichtl - Teedrogen und Phytopharmaka. Stuttgart, Germany:

Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft mbH; 2016:666-668.

- Van Wyk

BE. Food Plants of the World.

Portland, OR: Timber Press, Inc.; 2005:372.

- Rutto

LK, Xu Y, Ramirez E, Brandt M. Mineral properties and dietary value of raw and

processed stinging nettle (Urtica dioica

L.). International Journal of Food

Science. 2013;23:1-9.

- Di Virgilio

N, Papazoglou EG, Jankauskiene Z, Di Lonardo S, Praczyk M, Wielgusz K. The

potential of stinging nettle (Urtica

dioica L.) as a crop with multiple uses.

Industrial Crops and Products. 2015;68:42-49.

- Nettles. Drugs.com website. March 8,

2018. Available at: www.drugs.com/npp/nettles.html.

Accessed July 9, 2018.

- Thorne

Research. Urtica dioica; Urtica urens

(Nettle) monograph. Alternative Medicine

Review. 2007;12(3):280-284.

- Blumenthal

M, Busse WR, Goldberg A, et al, eds. The

Complete German Commission E Monographs: Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines.

Austin, TX: American Botanical Council; Boston, MA: Integrative Medicine

Publishing; 1998.

- European

Medicines Agency. Community herbal monograph on Urtica dioica L., Urtica

urens L., their hybrids or their mixtures, radix. Published September 24,

2012. Available at: www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Herbal_-_Community_herbal_monograph/2012/11/WC500134486.pdf.

Accessed on May 15, 2018.

- Behzadi

AA, Kalalian-Moghaddam, Ahmadi AH. Effects of Urtica dioica supplementation on blood lipids, hepatic enzymes

enzymes and nitric oxide levels in type 2 diabetic patients: A double blind,

randomized clinical trial. Avicenna

Journal of Phytomedcine. 2015;6(6):686-695.

- Arthritis-related

statistics. Center for Disease Control and Prevention website. January 11,

2018. Available at: www.cdc.gov/arthritis/data_statistics/arthritis-related-stats.htm. Accessed on May 15, 2018.

- Rayburn

K, Fleischbein E, Song J, et al. Stinging nettle cream for osteoarthritis. Alternative Therapies. 2009;15(4):60-61.

- Bakhshaee

M, Mohammad AH, Esmaeili M, et al. Efficacy of supportive therapy of allergic rhinitis

by stinging nettle (Urtica dioica) root extract: A randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Iranian

Journal of Pharmaceutical Research. 2017;15:112-118.

- Changping

M, Wang M, Aiyireti M, Cui Y. The efficacy and safety of Urtica dioica in treating benign prostatic hyperplasia: A

systematic review and meta-analysis. African

Journal of Traditional and Complementary Alternative Medicine. 2016;13(2):143-150.

- Codling

EE, Rutto KL. Stinging nettle (Urtica

dioica) growth and mineral uptake from lead-arsenate contaminated orchard

soils. Journal of Plant Nutrition.

2014;37:393-405.

- Basic

report: 35205, Stinging nettles, blanched (Northern Plains Indians). National

Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Legacy. USDA website. April 2018.

Available at: https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/306720.

Accessed July 5, 2018.

- Bauman

H, Applegate C. Food as medicine: shallot (Allium

cepa var. aggregatum, Amaryllidaceae).

HerbalEGram. 2017;14(2). Available at: http://cms.herbalgram.org/heg/volume14/02February/FAMShallot.html.

Accessed July 5, 2018.

- Farr

J. Stinging nettle spanakopita. YMC website. August 10, 2015. Available at: www.yummymummyclub.ca/blogs/jen-farr-hands-on-kitchen/20150729/stinging-nettle-spanakopita-recipe.

Accessed July 5, 2018.

|