By Hannah Baumana and Jamie Moser,

MSb

a HerbalGram Associate Editor

b ABC

Dietetics Intern (Texas State University, 2019)

Editor’s

Note: Each month,

HerbalEGram highlights a conventional food and briefly explores its history,

traditional uses, nutritional profile, and modern medicinal research. We also

feature a nutritious recipe for an easy-to-prepare dish with each article to

encourage readers to experience the extensive benefits of these whole foods.

With this series, we hope our readers will gain a new appreciation for the

foods they see at the supermarket and frequently include in their diets.

The basic materials for this series were compiled by

dietetic interns from Texas State University in San Marcos and the University

of Texas at Austin through the American Botanical Council’s (ABC’s) Dietetic

Internship Program, led by ABC Education Coordinator Jenny Perez. We would like to

acknowledge Perez and ABC Chief Science Officer Stefan Gafner, PhD, for their

contributions to this project.

Overview

The Brazil nut (Bertholletia excelsa) is the only known species in the genus Bertholletia and is a large tropical

forest tree in the Lecythidaceae family. The tree commonly grows throughout Brazil, the Guianas, Venezuela,

eastern Colombia, eastern Peru, and eastern Bolivia.1,2 It is among

the largest in the Amazon rainforest and reaches more than 48 meters (160 feet)

in height. The species often is found scattered in large forests on the banks

of the Amazon River, Rio Negro, and Orinoco River.

The Brazil nut tree has co-evolved with the help of the euglossine

bee, also called orchid bee or long- tongued bee, which pollinates its

heavy-lidded flowers. Once pollinated, the flower can then develop into a full

fruit.3 Each mature tree can produce up to

300 fruit pods in a season, which ripen at the end of the tree’s thick branches

and take approximately 14 months to mature.3,4 The large fruit pods are

roughly the size of a baseball and can weigh up to two kilograms (4.5 pounds). Each

fruit pod has a hard, woody shell that contains eight to 24 triangular seeds

that are up to two centimeters (3/4 inch) wide and five centimeters (two inches)

long. The seed, or nut kernel, is white and covered with dark brown skin.3 tongued bee, which pollinates its

heavy-lidded flowers. Once pollinated, the flower can then develop into a full

fruit.3 Each mature tree can produce up to

300 fruit pods in a season, which ripen at the end of the tree’s thick branches

and take approximately 14 months to mature.3,4 The large fruit pods are

roughly the size of a baseball and can weigh up to two kilograms (4.5 pounds). Each

fruit pod has a hard, woody shell that contains eight to 24 triangular seeds

that are up to two centimeters (3/4 inch) wide and five centimeters (two inches)

long. The seed, or nut kernel, is white and covered with dark brown skin.3

Production of Brazil nuts increased from 3,557 tons in

1944 to approximately 95,000 tons in 2014.4 Brazil nuts are

harvested almost entirely from wild trees during the six-month rainy season

(January through June). Once harvested, the pods are sent downriver for

processing. Brazil nut production consists of processing (cleaning, drying and

soaking, peeling the nuts, drying the peeled nuts), sorting (by size, specific

gravity, color, or damage), and packaging.

Historical and Commercial Uses

For centuries,

the indigenous tribes of the Amazon have relied on the nut and other parts of

the Brazil nut tree as a staple of their diet and trading commodity.4 Indigenous

tribes commonly used a bark infusion to ease liver ailments and chronic

diseases. Traditionally, the nuts were eaten raw, grated with the thorny stilt

roots of Socratea palm (Socratea

exorrhiza, Arecaceae) into a white mush known as leite de castanha (“Brazil nut milk”), or stirred into cassava (Manihot esculenta, Euphorbiaceae) flour.

These calorie-dense, high-protein,

high-fat, high-fiber preparations are a valuable source of nutrition for rural

communities.

In addition to its value as a nutrition source, the Brazil

nut is an important economic plant for Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, and the Ivory

Coast. It is exported primarily to England, France, the United States, and

Germany.1 In an effort to maximize the yield of the Brazil nut tree,

unsellable remnants of processed nuts are used in food products, such as mixed

nut blends, cereal bars, and chocolate, and ground for use as a flour. The pod

and shell have been formulated into a fuel source, as well as processed to

produce recycled wood and handcrafted items. The oil pressed from the Brazil

nut is clear or yellowish and is sweet smelling and tasting. Composed mainly of

palmitic, oleic, linoleic, and alpha-linolenic acids, this oil is used in the

cosmetic industry for its emollient properties and as a culinary ingredient.4

Phytochemicals

and Constituents

Brazil nuts are a rich source of unsaturated fatty acids,

protein, fiber, micronutrients, vitamins, and other phytochemicals. Their

macronutrient composition is approximately 18% protein, 13% carbohydrates, and

69% fat.1 Having one of the highest percentages of unsaturated fat

of the tree nuts, Brazil nuts primarily are composed of monounsaturated fatty

acids (MUFAs) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs).5 Sterols are also present in Brazil

nuts in significant quantities. Plant sterols are lipids, which in humans can

act to promote cardiovascular health by reducing low-density lipoprotein (LDL)

cholesterol levels.6

Due to

its high contents of alpha- and gamma-tocopherol, Brazil nuts are a rich source

of antioxidants.3 Brazil nuts also have been

found to contain the highest content of squalene compared to other tree nuts,

which is an essential building block of steroid hormones.5 While providing four grams of

protein per one-ounce serving, Brazil nuts have a lower protein content than

other tree nuts.3 Of the proteins present, Brazil nuts are rich in sulfur-containing amino

acids, including cysteine and methionine. Brazil nuts contain high

concentrations of micronutrients, including selenium, magnesium, phosphorus,

and thiamine (vitamin B1). They also provide a substantial amount of

niacin (vitamin B3), vitamin E, pyridoxine (vitamin B6),

calcium, iron, potassium, zinc, copper, arginine, and flavonoids.7 Due to

its high contents of alpha- and gamma-tocopherol, Brazil nuts are a rich source

of antioxidants.3 Brazil nuts also have been

found to contain the highest content of squalene compared to other tree nuts,

which is an essential building block of steroid hormones.5 While providing four grams of

protein per one-ounce serving, Brazil nuts have a lower protein content than

other tree nuts.3 Of the proteins present, Brazil nuts are rich in sulfur-containing amino

acids, including cysteine and methionine. Brazil nuts contain high

concentrations of micronutrients, including selenium, magnesium, phosphorus,

and thiamine (vitamin B1). They also provide a substantial amount of

niacin (vitamin B3), vitamin E, pyridoxine (vitamin B6),

calcium, iron, potassium, zinc, copper, arginine, and flavonoids.7

Brazil nuts have been reported to contain the

highest known level of selenium of any food.7 The selenium content of Brazil

nuts has been found to vary from region to region, tree to tree, as well as

seed to seed.1 Selenium distribution is dependent on multiple

factors, such as the selenium content of the soil, chemical form of selenium in

the soil, presence of heavy metals, rain intensity, absorption ability of the

tree’s root system, and tree maturity. The high selenium content observed in

Brazil nuts may be the result of selenium’s chemical similarity to sulfur,

which is often deficient in Amazon soils, thereby forcing many plants to use

selenium instead of sulfur.2

Like other nuts, Brazil nuts are a good dietary source of phytochemicals

such as phenolic acids, flavonoids, tocopherols, and phytosterols.3 Extracts of Brazil nuts show strong antioxidant and

antiproliferative activities in vitro, with the strongest effects observed in

the presence of selenium. Of the phytochemicals present in Brazil nuts,

phenolic compounds are present in the highest concentration. The main compounds

identified include gallic acid, ellagic acid, vanillic acid, protocatechuic

acid, and catechin. Within the nut, the outer brown skin contains a higher

concentration of phenolics compared to the nutmeat itself. Regarding other

phytochemicals, flavan-3-ols are found in the highest concentration, with

isoflavones, anthocyanins, and flavonols, as well as carotenoids present.

Modern

Research

Selenium is an essential nutrient for human

health, and its biological functions are mediated by the expression of 25

different selenoproteins, which are essential for thyroid hormone metabolism

and act as potent antioxidants.2,3 Selenium has been shown to be anti-aging, immune-stimulating,

and important in thyroid health. It also has been shown to offer protection

against heart disease, certain forms of cancer, viral infection, and

progression of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).2 Selenium may protect the body

from damage associated with heavy metals due to its ability to bind to

these elements and convert them into biologically inert conjugates.8,9

Research on selenium indicates

it may reduce the rate of miscarriages and promote male fertility.8

Selenium

deficiency is associated with a wide variety of health issues, including

neurological, endocrine, muscle, and cardiovascular disorders, and it may

contribute to Keshan disease (congestive cardiomyopathy) and Kashin-Beck

disease (bone disease characterized by deformed growth).8 Consuming

one Brazil nut daily has been shown to increase blood

levels of selenium and the activity of various selenium-dependent enzymes.8,10 Natural and food-derived forms of

selenium may have beneficial effects not observed in supplemental forms of

selenium due to the synergistic effects of selenium and other beneficial

compounds present within the nut. Selenium

deficiency is associated with a wide variety of health issues, including

neurological, endocrine, muscle, and cardiovascular disorders, and it may

contribute to Keshan disease (congestive cardiomyopathy) and Kashin-Beck

disease (bone disease characterized by deformed growth).8 Consuming

one Brazil nut daily has been shown to increase blood

levels of selenium and the activity of various selenium-dependent enzymes.8,10 Natural and food-derived forms of

selenium may have beneficial effects not observed in supplemental forms of

selenium due to the synergistic effects of selenium and other beneficial

compounds present within the nut.

Glutathione peroxidase

(GPx) and thioredoxin reductase (TrxR) are important selenium-containing enzymes

that act to promote multiple health benefits possibly via their antioxidant

properties.11 GPx functions to prevent the oxidative modification of

lipids, inhibit platelet aggregation, and modulate inflammation.12 Normal

GPx activity also has been

found to be associated with reduced risk of prostate cancer, lung cancer, and

colon cancer.8 In addition, GPx activity has been shown to play a role in thyroid

health. In autoimmune thyroiditis, a dysregulation of thyroid hormone

metabolism and/or thyroid tissue damage occurs. Incidence of autoimmune

thyroiditis has been linked to the decrease of selenium-dependent GPx activity

in thyroid cells. According

to a meta-analysis conducted by Ventura et al., consumption of 200 mcg of

selenium daily (approximately two brazil nuts per day) was found to be beneficial

for modulating immune function in those living with autoimmune thyroiditis.13

Selenium status has been shown to be

associated with mild cognitive impairment (MCI).14 MCI commonly

occurs in the elderly population, which is at risk for selenium deficiency

related to increased nutrient requirements, metabolic changes, lower nutrient

absorption, and changes in diet. In a randomized placebo-controlled study of 31

older adults with MCI, one Brazil nut daily for six months was

enough to reverse selenium deficiency and resulted in some improvement of

cognitive functions. These improvements are thought to be the result of both

the selenium content of the nut as well as its high content of phenolic

compounds, which allow for an increase in antioxidant activity and promote normal

mitochondrial function, synaptic transmission, axonal transport, and inhibition

of neuroinflammation.

Brazil

nuts are a rich source of MUFAs and PUFAs and therefore have been shown to be

beneficial for cardiovascular health. In a randomized crossover study,

intake of either 20 g or 50 g of Brazil nuts daily by 10 healthy subjects was

associated with increased high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol

concentration and a reduction of LDL concentration.11 Additionally, in a randomized placebo-controlled

study of 17 obese female adolescents, it was observed that supplementation with

three to five Brazil nuts per day (15-25 g per day) for 16 weeks positively

influenced lipid profiles (total cholesterol, LDL, and glucose levels).5

Consumer

Considerations

Despite the numerous potential health

benefits provided by Brazil nuts, daily consumption should be limited. Selenium intakes above the

Recommended Daily Allowance (RDA) of 55 mcg per day, or approximately one

Brazil nut, can result in an accumulation of selenium as selenomethionine in

tissues, which can lead to selenosis, with symptoms such as nail brittleness,

hair loss, peripheral paresthesia, decreased cognitive function, and skin lesions.1,15

Excessive Brazil nut intake can also lead to the accumulation of heavy metals

such as barium and strontium and carcinogenic elements such as radium.3,15

The presence of barium in Brazil nuts is thought to result from the presence of

hollandite ore in soils of the Amazon region. While there is no evidence that

strontium is toxic for adults, in children it may impair mineralization of the

developing bones.

Brazil nuts are commonly contaminated by fungi and their

metabolites (mycotoxins). Occasionally, aflatoxins present in Brazil nuts have

been reported to exceed limits accepted by European legislation (4 μg/kg).3

In the United States, federally mandated Good Manufacturing Practices (GMPs) have

been modified in an attempt to prevent contamination of tree nuts by

aflatoxins. Such preventative measures include multiple rounds of sorting and screening

of the nut during processing, as well as the disposal of damaged nuts that do

not meet processing standards.1 Despite these efforts to minimize

fungal growth and mycotoxin production, contamination remains an ongoing

challenge due to the hot and humid climatic conditions of the Amazon.

As with other tree nut allergies, allergic reactions to

Brazil nuts are usually immunoglobulin E (IgE) mediated. While allergic

reactions to Brazil nuts are fairly rare, immunological studies have found

several proteins in the nut with potent antigenic components.3 Symptoms of an

allergic reaction vary from swelling and itching around the mouth to acute and

life-threatening anaphylaxis.16

Nutrient Profile17

Macronutrient

Profile: (Per six Brazil nuts [approx. 1 oz])

185 calories

4.0 g protein

3.5 g carbohydrate

18.8 g fat

Secondary

Metabolites: (Per six Brazil nuts [approx. 1 oz])

Excellent

source of:

Selenium: 542 mcg (985% DV)

Magnesium: 106 mg (27% DV)

Copper: 0.5 mg (25% DV)

Phosphorus: 205 mg (20% DV)

Very good

source of:

Manganese: 0.3 mg (17% DV)

Thiamin: 0.2 mg (12% DV)

Good

source of:

Dietary Fiber: 2.1 g (8% DV)

Vitamin E: 1.6 mg (8% DV)

Zinc: 1.1 mg (8% DV)

Calcium: 45.2 mg (5% DV)

Potassium: 186 mg (5% DV)

Iron: 0.7 mg (4% DV)

Folate: 6.2 mcg (2% DV)

Also provides:

Pantothenic Acid: 0.1 mg

Betaine: 0.1 mg (no daily value established)

Choline: 8.1 mg (no daily value established)

DV = Daily Value as established by the US

Food and Drug Administration, based on a 2,000-calorie diet.

|

Recipe: Mixed Nut Milk

(Makes six half-cup servings)

Courtesy of Jamie Moser

Ingredients:

- 1/4 cup raw cashews

- 1/3 cup raw pumpkin seeds

- 6 Brazil nuts

- 6 cups of water

- 1/8 teaspoon salt

- 1 tablespoon maple syrup

Directions:

- Combine the nuts and seeds in a bowl and

cover with three cups of water. Soak overnight in the refrigerator.

- Drain and rinse the nuts and seeds. Add them to

the jar of a high-speed blender.

- Add remaining three cups water, salt, and

maple syrup to the blender. Blend on high speed for five minutes.

- Strain mixture through a nut milk bag, squeezing

well to extract the maximum amount of nut milk. Store in

refrigerator and use within 3-5 days.

|

Image credits (top to bottom):

Brazil nut tree canopy. ©2019 Steven Foster.

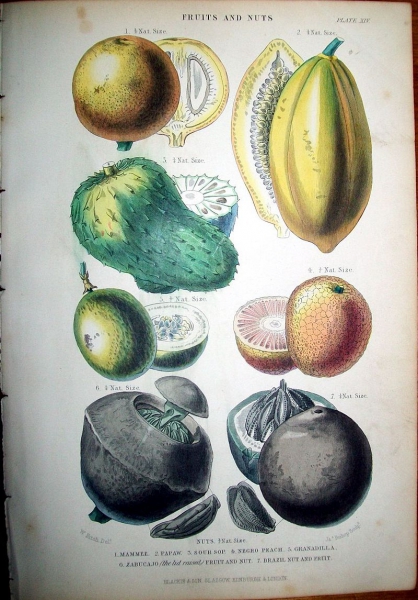

Illustration of tropical fruits and nuts, including Brazil nut (bottom right), from A History of the Vegetable Kingdom by William Rhind. 1874.

Brazil nuts and their pods. ©2019 Steven

Foster.

References

- Freitas-Silva O, Venâncio A. Brazil nuts:

Benefits and risks associated with contamination by fungi and mycotoxins. Food Res Int. 2011;44:1434-1440.

10.1016/j.foodres.2011.02.047.

- Preedy V, Watson R, Patel

V. Nuts and Seeds in Health and Disease Prevention. London, UK: Academic Press; 2011.

- Cardoso

BR, Duarte GBS, Reis BZ, Cozzolino SMF. Brazil nuts: Nutritional composition,

health benefits and safety aspects. Food

Res Int. 2017;100(Pt 2):9-18.

- Taylor L. Brazil Nut. Tropical

Plant Database website. 2005. Available at: www.rain-tree.com/brazilnu.htm.

Accessed April 8, 2019.

- Maranhão PA, Kraemer-Aguiar LG, De Oliveira CL, et al.

Brazil nuts intake improves lipid profile, oxidative stress and microvascular

function in obese adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Nutr Metab (Lond). 2011;8(1):32.

- Abumweis SS, Barake R, Jones PJ. Plant

sterols/stanols as cholesterol lowering agents: A meta-analysis of randomized

controlled trials. Food Nutr Res.

2008;52.

- John JA, Shahidi F. Phenolic compounds and

antioxidant activity of Brazil nut (Bertholletia

excelsa). J Func Food. 2010;2:196-209.

10.1016/j.jff.2010.04.008.

- Yang R,

Liu Y, Zhou Z. Selenium and selenoproteins, from structure, function to food resource

and nutrition. Food Science and

Technology Research. 2017;23:363-373. 10.3136/fstr.23.363.

- Zwolak I, Zaporowska H.

Selenium interactions and toxicity: a review. Selenium interactions and

toxicity. Cell Biol Toxicol.

2012;28(1):31-46.

- Thomson

CD, Chisholm A, Mclachlan SK, Campbell JM. Brazil nuts: an effective way to

improve selenium status. Am J Clin Nutr.

2008;87(2):379-84.

- Colpo E, Vilanova CD, Brenner Reetz LG, et

al. A single consumption of high amounts of the Brazil nuts improves lipid

profile of healthy volunteers. J Nutr

Metab. 2013;2013:653185.

- Cominetti C, De Bortoli MC, Purgatto E, et al.

Associations between glutathione peroxidase-1 Pro198Leu polymorphism, selenium

status, and DNA damage levels in obese women after consumption of Brazil nuts. Nutrition. 2011;27(9):891-896.

- Ventura M, Melo M, Carrilho F. Selenium and thyroid

disease: From pathophysiology to treatment. Int

J Endocrinol. 2017;2017:1297658.

- Cardoso BR, Apolinário D, Da Silva Bandeira

V, et al. Effects of Brazil nut consumption on selenium status and cognitive

performance in older adults with mild cognitive impairment: a randomized

controlled pilot trial. Eur J Nutr.

2016;55(1):107-16.

- Office of

Dietary Supplements - Selenium. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements website. Available

at: https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/Selenium-HealthProfessional/. Accessed

April 8, 2019.

- Arshad

SH, Malmberg E, Krapf K, Hide DW. Clinical and immunological characteristics of

Brazil nut allergy. Clin Exp Allergy.

1991;21(3):373-6.

- Basic

report: 12078 Nuts, brazilnuts, dried, unblanched. National Nutrient Database

for Standard Reference Legacy Release. United States Department of Agriculture

website. April 2018. Available at: https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/12078.

Accessed May 14, 2019.

|