Editor’s Note: Each month, HerbalEGram highlights a conventional food and

briefly explores its history, traditional uses, nutritional profile, and modern

medicinal research. We also feature a nutritious recipe for an easy-to-prepare

dish with each article to encourage readers to experience the extensive

benefits of these whole foods. With this series, we hope our readers will gain

a new appreciation for the foods they see at the supermarket and frequently

include in their diets.

We would like to acknowledge ABC Chief

Science Officer Stefan Gafner, PhD, for his contribution to this project. By Jenny

Pereza and Hannah Baumanb

a ABC’s Education

Coordinator

b HerbalGram Associate Editor

Overview

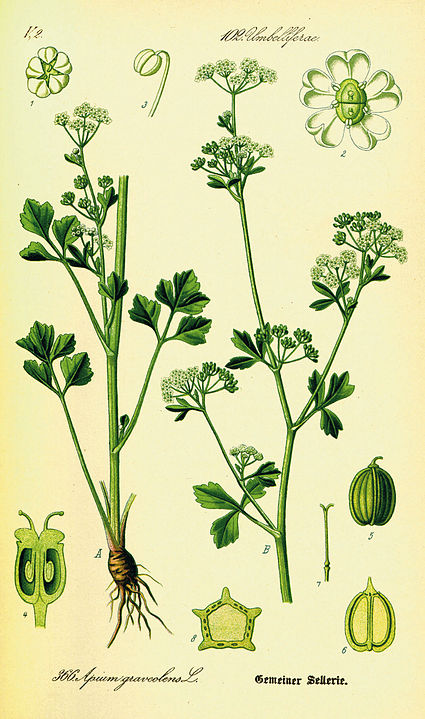

Celery

(Apium graveolens) is an herbaceous

biennial in the Apiaceae family, which includes other widely cultivated

vegetables and herbs with feathery, pinnate leaves and aromatic seeds, such as

carrot (Daucus carota), parsley (Petroselinum crispum), coriander (Coriandrum sativum), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), and dill (Anethum graveolens). Native to marshy,

salty soils in coastal Europe and temperate Asia, wild celery (A. graveolens var. secalinum), also known as cutting celery or smallage, was

originally harvested for its strong-flavored leaves, which were used as a

condiment in soups and stews.1,2

Celery

thrives in cool, mild climates and requires high levels of moisture.3,4

Growing to a height of 15-24 inches (38-61 cm), celery has long, fibrous petioles

formed by conically arranged stalks joined at the base that surround the heart

of the celery plant.2 The stalks each produce three to five bright

green, pinnate leaves at the tip of the stalk.2,5-7 Celery’s small

white or yellow flowers appear in umbels from January to August during the

plant’s second year of growth. The celery fruits, or schizocarps, consist of

two united carpels (mericarps), each containing a brown, ridged, ovoid-shaped,

very small seed, approximately 1.3 mm in length.9 These fruits,

known in commerce as “celery seed,” have a floral odor and slightly pungent

taste, and typically ripen in August and September.9,10

Celery

is cultivated worldwide.4 Celery’s Latin binomial, Apium graveolens, translates to

“strongly smelling” and alludes to celery’s aromatic compounds.1 In

temperate climates, including those of India, Southeast Asia, France, and

Italy, celery is grown for its aromatic seeds, specifically for use in perfumes

and as a flavoring.1,2 The succulent, rigid stalk can be eaten raw

or cooked, and the fleshy taproot, known as celeriac, is eaten raw, roasted,

mashed, or pureed. The seeds are used in cosmetics and condiments.1,4,10

Historical and Commercial Uses

Celery

was cultivated from its wild ancestor in the 16th or 17th century in the

northern Mediterranean.2 During the 1700s, celery began to be

cultivated as a food product and medicine throughout Europe.6 Cultivated

celery has been bred for its elongated, thick, fleshy, ribbed, milder-tasting

stalks, while wild celery is grown for its bitter leaves.2 By the

early 19th century, four varieties of celery were cultivated in the United

States, where the plant gained popularity as a salad vegetable.2,6 Three

varieties of celery are the most commonly cultivated: Chinese celery (var. secalinum), which is used sparingly as a

condiment due to its strong, bitter taste; stalk celery (var. dulce), which is eaten raw in salads or

cooked; and celeriac or “turnip-rooted celery” (var. rapaceum), which is grown for its enlarged root. Celeriac is popular

in European cuisine and its seeds also are used for making commercial celery

salt.5

Celery

seed is a lesser-known spice that has been used for thousands of years.11

The Greeks, Romans, and Egyptians used the bitter leaves and aromatic seeds of

the celery plant in rituals and as a condiment and medicine.2,4 The

use of celery was common in celebration practices as a symbol with two meanings:

death and victory.7 Celery leaf garlands were used to adorn athletes

in award ceremonies and to honor the deceased at funerals.2,4,7 Considered

a symbol of Chthonian deities (living in or beneath the earth) from ancient

Greek mythology, celery’s spicy odor and dark leaf color was associated with

the underworld and death.1,4,5,7 In ancient Greece, celery leaf crowns

were placed on the dead and celery wreaths were draped across graves.7

Celery leaves and flowers were part of the garlands found in the Egyptian Pharaoh

Tutankhamun’s tomb (died ca. 1321 BCE).1

Prior

to the 16th century, the celery plant was used more as a medicine than a food.1

Celery seeds, leaves, stem, and root are used in a variety of traditional

medicine systems, including the Unani tradition of ancient Persia and Arabia, Indian

Ayurveda, and Chinese herbal medicine. As

an herbal preparation, celery seeds were consumed fresh or as a water

decoction, or the seed powder or extracts were used. The first century medical

text, De Medicina, written by Roman

encyclopedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus, listed the use of powdered celery seed pills

for pain relief.1 Powdered celery seeds were blended with honey to

create a paste used topically as a poultice for a variety of inflammatory

conditions such as boils, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, sciatica, and backache.12 Prior

to the 16th century, the celery plant was used more as a medicine than a food.1

Celery seeds, leaves, stem, and root are used in a variety of traditional

medicine systems, including the Unani tradition of ancient Persia and Arabia, Indian

Ayurveda, and Chinese herbal medicine. As

an herbal preparation, celery seeds were consumed fresh or as a water

decoction, or the seed powder or extracts were used. The first century medical

text, De Medicina, written by Roman

encyclopedist Aulus Cornelius Celsus, listed the use of powdered celery seed pills

for pain relief.1 Powdered celery seeds were blended with honey to

create a paste used topically as a poultice for a variety of inflammatory

conditions such as boils, rheumatoid arthritis, gout, sciatica, and backache.12

In

Unani medicine, the Arabs obtained knowledge of the use of tukhme karafs, or celery seeds, from Greek physicians including

Dioscorides (first century CE) and Theophrastus (died 287 BCE).12

The seeds of celery are rich in pungent, astringent volatile oils that are used

in a variety of preparations, including teas/decoctions and pastes.12

Celery seeds are considered a heart tonic and used to lower blood pressure.10

Other indications include hepatic and spleen disorders, brain disorders, body

pain, and sleep disturbances.10 Celery seed decoctions commonly were

used for breathing difficulties such as asthma, bronchitis, and pleurisy, and

were considered effective for treating measles and all types of fevers.12

Celery seed decoctions also were used to help dissolve both kidney and bladder

stones and were also indicated in cases of sexual debility or low libido. However,

celery seed was contraindicated in cases of venomous stings due to its ability

to thin the blood and rapidly circulate the venom through the body.10

In Ayurveda,

the traditional medicine system of India, celery stalk juice was used for

chronic lung congestion and weight loss as well as to stimulate poor appetite.8

The root, leaf, and seed are used in various preparations for purifying the

blood, regulating digestion and bowel movements, calming the nerves, and curing

gallstones and kidney stones.9 Celery seed tea commonly is used to

relieve indigestion, flatulence, and griping pains.11 Celery seed

and root are considered to have aperient (laxative), carminative

(digestion-enhancing), diuretic, emmenagogue (uterine-stimulating),

galactogogue (breastmilk-promoting), nervine (calming), stimulant, and tonic

properties.8,11 Celery root was used for its diuretic properties and

as a remedy for colic.3,13 Celery root tinctures are used as a

diuretic in hypertension and urinary disorders.11

India’s

Materia Medica lists celery as a

diuretic, a litholitic (breaks urinary stones), an emmenagogue, and a

carminative adjunct to purgatives.13 Celery is a preventative

treatment for rheumatism and gout and is also indicated as an antispasmodic for

treating bronchitis, asthma and chronic lung congestion, and as a

blood-purifying alterative for chronic skin disorders such as psoriasis.3,8,13

Similar to Unani traditional medicine, celery seed decoctions are used as an

aphrodisiac to enhance libido and as a nervine to calm anxiety and insomnia.11

Celery seed extract is used similarly to improve kidney function and treat gout

as well as bladder and urinary tract infections.9,11 The typical

medicinal dose for celery seed is three to five grams.12

Celery,

specifically Chinese celery (A.

graveolens var. secalinum), was

independently cultivated in China where it has been used as an important food

and medicine since the fifth century.2 Celery is categorized as

having a bitter taste and a cooling thermal nature and is used to relieve water

retention and control high blood pressure. Celery’s detoxifying phytochemicals

reduce blood acidity or acidosis common with tissue inflammation associated

with gout and diabetes.14 Mineral-rich celery stalk juice

formulations are used as a dietary therapy to renew joints, connective tissue,

arteries, and veins.14

According

to the German Commission E, celery is described as a natural diuretic and is noted

for use for acidosis or “blood purification,” for regulating bowel movements,

alleviating rheumatic complaints, gout, bladder or kidney stones, as well as

for weight loss due to malnutrition, exhaustion, loss of appetite, and to calm

nervousness.15 However, the Commission E listed celery as an “Unapproved

Herb” due to a lack of adequate scientific or clinical evidence to support such

uses at the time the commission reviewed the pertinent literature on celery (1991).

Celery’s

crunchy texture and mildly salty flavor is versatile whether cooked or eaten

raw as a salad vegetable.2,6 Celery is an integral ingredient in

many cuisines. It is one of three vegetables in the “holy trinity” of

Louisiana’s Creole and Cajun cuisine along with green bell pepper (Capsicum

annuum, Solanaceae) and onion (Allium cepa, Amaryllidaceae) and the

French mirepoix along with onion and carrot. When selecting celery in

the grocery store, consumers should look for vegetables that are light green,

with fresh-looking leaves and firm, crisp stalks.6

Although

the stalks of celery may be most familiar to consumers, its leaves, roots, and

seeds are used as food and as seasoning.6 Celery leaves can be used similarly

to parsley and contain more calcium, potassium, and vitamin C than other parts

of the celery plant. Celery root can be prepared like other root vegetables.

Celery

leaves, stalks, and seeds are used to flavor canned soups, sauces, pickles,

sauerkraut, tomato products, and meats.9 Celery seeds can also be

used in baked products.2,9

Phytochemicals and Constituents

Celery

is a nutrient-dense, mineral-rich vegetable. A 100-g serving of celery stalks

(about one cup, chopped) contains only 14 calories, 95% water, and 1.6 g fiber.6

One cup of celery stalks provides 24% of the recommended daily allowance (RDA)

of vitamin K, moderate amounts of vitamins A and C, folate, potassium, and

manganese, significant amounts of all other B vitamins, vitamin E, calcium,

copper, iron, magnesium, phosphorus, silicon and zinc.6-7,9,11 Celery’s

salty flavor is indicative of a higher sodium content than most vegetables,

which is offset by its high potassium content as well as celery’s 3-n-butylphthalide (3nB), which relax

smooth muscles, including blood vessels.6,9 The amount of sodium in

celery is insignificant even for the most salt-sensitive individuals. One

celery stalk contains 32 mg of sodium and 104 mg of potassium while delivering

only 20 calories as a carbohydrate.6 Due to the 3:1 ratio balance of

potassium to sodium, consuming celery-based juices after exercise can replace

lost electrolytes.6,9

Celery

seeds and oleoresin contain linoleic acid, a monounsaturated fatty acid (MUFA)

which provides cardiovascular benefits.9 Celery oleoresin is commonly

used in perfume making and consists of volatile oils, fixed oils, wax, and

resin obtained from repeated steam distillation of coarsely ground celery

flakes/powder. Celery seeds contain approximately 2% essential oil that is used

in the flavor and fragrance industries.9 Volatile oils present in

celery seed, predominately d-limonene and myrcene, decrease free radical

production, while the sesquiterpenes eugenol and piperitone are associated with

pain relief.9,12 Celery essential oil also contains approximately

20% phthalides, including 3nB. When used for its aromatic properties, celery

seed oil has a calming effect on the central nervous system and has

antispasmodic, sedative, and anticonvulsant properties.8 Celery’s

essential oil has antifungal activity and inhibits bacteria including Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Shigella

dysenteriae, Streptococcus faecalis, and Salmonella

typhi.9,10 In one study, celery seed oil (with 5% vanillin) was

found to repel mosquitos better than commercially used repellent.10 Celery seeds contain approximately 2% essential oil that is used

in the flavor and fragrance industries.9 Volatile oils present in

celery seed, predominately d-limonene and myrcene, decrease free radical

production, while the sesquiterpenes eugenol and piperitone are associated with

pain relief.9,12 Celery essential oil also contains approximately

20% phthalides, including 3nB. When used for its aromatic properties, celery

seed oil has a calming effect on the central nervous system and has

antispasmodic, sedative, and anticonvulsant properties.8 Celery’s

essential oil has antifungal activity and inhibits bacteria including Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Shigella

dysenteriae, Streptococcus faecalis, and Salmonella

typhi.9,10 In one study, celery seed oil (with 5% vanillin) was

found to repel mosquitos better than commercially used repellent.10

Bioactive

compounds known as phthalides (compounds that contain a chemical moiety known

as lactone) are abundant throughout celery and other Apiaceae plants, such as lovage

(Levisticum officinale), and appear

to protect against cancer, high blood pressure, and cholesterol based on

evidence from in vitro and animal studies.9,11 The 3nB from celery

seed extract has been evaluated for its ability to both treat and prevent

inflammation and gastrointestinal irritation while promoting smooth muscle

relaxation.9 Phthalides are responsible for celery’s flavor.11

Research indicates that 3nB lowers uric acid production by inhibiting xanthine

oxidase.6,9 Sedanolide has been found to reduce tumor growth in vivo.9

Sedanolide and 3nB isolated from celery seed oil have demonstrated the ability

to induce high amounts of glutathione S-transferase (GST), an important

detoxification enzyme. Additionally, 3nB and sedanolide from celery stalk and

seed have been linked to its traditional and aromatic uses to calm and mildly

sedate the central nervous system.9,12

All

parts of the celery plant contain phenolic acids such as caffeic acid, chlorogenic

acid, chrysoeriol, p-coumaric acid, coumarolyquinic acid, and ferulic acid.3,16

Additionally, celery stalk, seed, and root are rich in antioxidant flavonoids including

apigenin, apiin, luteolin, and kaempferol. Animal studies have demonstrated

that apigenin improves blood glucose levels and antioxidant status, possesses

antiplatelet activity, and stimulates adult neurogenesis.10,16 The

anti-inflammatory effects may be partly due to the presence of apiin, a

glycoside of apigenin.17 Apiin increases the activity of

detoxification enzymes, including superoxide dismutase (SOD), GSH peroxidase,

and catalase, in vitro.3 Celery also contains coumarins, including

furanocoumarins such as bergaptene, isopimpinellin, and psoralene, which are

known to be phototoxic. However, furanocoumarin concentrations in stalks and

root are below the threshold to cause any phototoxic reactions when consumed as

part of typical diet.8,10,18

The

polyphenol content of celery coupled with its vitamin C content enhances

celery’s ability to strengthen the immune system and reduce the severity of

inflammatory conditions by enhancing detoxification processes in the

body.8,9 Like vitamin C, celery’s flavonoids reduce reactive oxygen

species (ROS) and increases SOD enzymes.3 Celery seed also contains

the phenylpropanoid apiol, which is a mild diuretic and urinary antiseptic,

making it particularly useful in treating genitourinary conditions, including

urinary tract infections.3,8 Celery seed stimulates the kidneys,

promotes urine flow, and assists in the breakdown of uric acid and other

metabolic wastes.11

Modern Research and Potential Health

Benefits

There

is limited human research that explores the therapeutic properties of celery.

Animal studies have shown celery’s ability to reduce blood glucose, cholesterol,

and blood pressure, which benefits cardiovascular health.3 Studies

focused on the nutrients and phytochemicals found in celery leaf, seed, and

root have demonstrated a wide range of potential health benefits including improved

male fertility by increasing spermatogenesis, and protection against

cardiovascular disease, diabetes, liver diseases, urinary tract obstruction,

gout, gastric ulcers, rheumatic conditions, and neurodegenerative diseases.8

Further clinical research is needed to validate these potential uses and to determine

the effective individual dose of celery in order to obtain maximum health

benefits.9

Anti-Hypertensive Activity

High

blood pressure or hypertension is one of the biggest risk factors for heart

attack or stroke. More than 60 million people in the United States have

hypertension.19 Coumarins that naturally occur in plants (as opposed

to concentrated coumarins commonly prescribed as blood thinners, such as

Coumadin®) gently tone the vascular system, lower blood pressure,

and may be useful in treating migraines.6,9 The 3nB content in

celery is correlated with lower blood pressure by acting as both a diuretic and

a vasodilator via increasing prostaglandin synthesis and by blocking calcium

channels.9,20 In animal studies, daily consumption of 3nB (an

equivalent dose of approximately four celery ribs) lowered blood pressure by 12

to 14% and cholesterol by 7%.6,19 Animal studies have also confirmed

that 3nB lowers blood cholesterol and reduces arterial plaque formation, which

may increase the elasticity of blood vessels.19

Results

from a pilot clinical trial that evaluated the blood pressure-lowering effects

of celery seed extract in hypertensive patients found a statistically

significant decrease in both systolic blood pressure (SBP) and diastolic blood

pressure.19 Following a seven-day wash-out period, 30 mildly to

moderately hypertensive patients were given 75 mg of celery seed extract

standardized to contain 85% 3nB (no other information given) dosed twice daily,

one capsule in the morning and one capsule in the evening for a total of six weeks.

At week three and week six, there was a statistically significant decrease in

SBP and DBP compared to baseline. The results indicate clinically relevant

blood pressure-lowering effects that warrant larger, more conclusive

double-blind studies.

Unlike

conventional antihypertensive medications, such as beta-blockers, angiotensin

converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, and calcium channel blockers that often

leave patients feeling tired or forgetful, celery seed extract does not lower

cerebral blood circulation.19 In fact, in animal models of stroke,

recovery of neurological and brain function improved significantly after the

use of celery seed extract. For stroke prevention and recovery, celery seed

extract may offer significant benefits due to its ability to improve blood flow,

protect the brain, and enhance energy production.

Detoxification Activity

Celery

provides a wide variety of flavonoids and phenolic acids that play a vital role

in neutralizing free radicals and preventing damage to pancreatic β-cells.16

Celery contains abundant phytonutrients that improve the elimination of

metabolic wastes and lower blood pH. Chronic inflammatory conditions like

arthritis traditionally have been treated with phytonutrients like those found

in celery.

I n a

clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of an unnamed celery seed extract,

participants who had chronic osteoarthritis and gout (a type of arthritis

characterized by a buildup of uric acid crystals from excess purine intake in

the joints) were given 34 mg of celery seed extract twice daily. Despite the

small dose, after three weeks of use, the participants experienced

statistically significant pain relief, with average pain reduction scores of 68%,

though some participants reported 100% relief from pain.6 Maximum

pain-relieving benefits were achieved after six weeks of using the standardized

extract. In patients suffering from gout, it was noted that 3nB lowered uric

acid production. n a

clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of an unnamed celery seed extract,

participants who had chronic osteoarthritis and gout (a type of arthritis

characterized by a buildup of uric acid crystals from excess purine intake in

the joints) were given 34 mg of celery seed extract twice daily. Despite the

small dose, after three weeks of use, the participants experienced

statistically significant pain relief, with average pain reduction scores of 68%,

though some participants reported 100% relief from pain.6 Maximum

pain-relieving benefits were achieved after six weeks of using the standardized

extract. In patients suffering from gout, it was noted that 3nB lowered uric

acid production.

Another

clinical study on a smaller group of patients with chronic arthritis-related

pain reported on the effects of 75 mg of celery seed extract twice daily for three

weeks.6 This higher dose produced even more clinically relevant and more

highly statistically-significant results in pain relief scores, physical

mobility, and quality of life. No adverse side effects were reported, but there

was a predictable diuretic effect. Celery extracts standardized to contain 85%

3nB are considered by some authors an effective treatment for rheumatism, or

arthritic and muscular aches and pains.6,9

Celery

seed extracts have demonstrated antioxidant activity in vivo with similar

hepatoprotective activity to that of silymarin from milk thistle (Silybum marianum, Asteraceae) seed.10

Histopathological studies showed the reversal of structural changes of the

liver induced by acetaminophen. Oral administration of celery seed extract (300

mg/kg) for six weeks prevented an increase in oxidative stress and hepatic

enzyme and bilirubin levels.9 An infusion of celery root increased

GSH and total antioxidant capacity, and celery leaf water extract increased GSH

but had no effect on total antioxidant capacity.3

Cancer Preventive Activity

Celery

has been studied for its ability to prevent cancer though improving

detoxification processes in the body.6 Coumarins support immune

function and may prevent cancer not only by protecting cells from becoming

damaged by free radicals, but also enhancing white blood cell activity in

targeting and eliminating potentially harmful cells, including cancer cells.6,9

Researchers have investigated the antioxidant activity of celery in rats

treated with doxorubicin, a potent chemotherapeutic drug commonly used to treat

acute leukemias, lymphomas, and solid tumors.20

The

flavonoid apiin from celery leaves has shown to increase the activity of

detoxification enzymes including SOD, GSH peroxidase, and catalase.3

In an animal study, celery leaf juice provided protection from drug-induced

free radical damage while not interfering with the therapeutic effects of drugs

like doxorubicin.20 Clinical trials are needed to confirm these

effects in humans.

Celery

and other Apiaceae plants contain bitter-tasting polyacetylenes, potent

antifungal and antibacterial compounds that are cytotoxic against several solid

and leukemic cancer cell lines and also potentiate the cytotoxicity of other

anti-cancer drugs.21 Pure polyacetylenes cannot be used in medicinal

preparations due to their chemical instability and potential allergenicity when

concentrated. To access the protective benefits of bioactive polyacetylenes, it

is best to consume foods with high amounts of these compounds, such as celery,

parsnips (Pastinaca sativa, Apiaceae),

and parsley.

Insulin Regulation Activity

Insulin

is a hormone produced by the β-cells of the

pancreas, which regulates carbohydrate metabolism.16 Hyperglycemia,

an indication of pre-diabetes, and diabetes occurs when insulin secretion or

insulin regulation are abnormal. Chronic hyperglycemia and uncontrolled

diabetes are the major causes of diabetes mellitus (DM). Long-term use of

anti-diabetic medication is costly and is associated with weight gain, bone

loss, and cardiovascular disease. Celery leaf extract has the potential as an adjuvant

anti-diabetic medicine with fewer side effects. Unlike most anti-diabetic

medications, celery’s phytonutrients affect the absorption of glucose in the

intestine rather than stimulating the pancreas to produce more insulin and also

decrease gluconeogenesis in the liver. It is believed that celery’s essential

oils, phenolic acids, and flavonoids contribute to its hypoglycemic effects.

In a

small randomized, placebo-controlled study, 16 elderly pre-diabetic participants

were divided into two groups to study celery’s effects on hyperglycemia.16

The control group received 250 mg placebo capsules containing magnesium stearate

and aerosol while the treatment group received a 250 mg dose of encapsulated celery

leaf extract three times daily, 30 minutes prior to meals, for 12 days. Pre-and

post-prandial blood glucose levels as well as insulin levels were obtained

twice: before and after treatment. In the celery group, pre-prandial blood

glucose levels decreased by 9.8% and post-prandial blood glucose levels

decreased by 19.5% after treatment, but it slightly increased plasma insulin

levels in elderly patients who were pre-diabetic.

Flavonoids

play an important role in managing pre-diabetes or metabolic syndrome.

Flavonoids reduce hyperglycemia, increase insulin resistance, control the

intestinal absorption of glucose and glucose metabolism in the liver, as well

as the digestion of carbohydrates, regulate cell-signaling AMP-activated

protein kinase pathways, and even improves glucose uptake and reduce oxidative

stress in skeletal muscle cells.16 High levels of sorbitol in

diabetic patients are linked to cataracts, retinopathy, and neuropathy.

Apigenin, a predominant flavonoid in celery, inhibits the aldose reductase,

which is a key enzyme in converting glucose to sorbitol. Both apigenin and

luteolin are being studied for their potential as sodium-glucose

cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitors in neuropathic diabetes. Kaempferol reduces

hyperglycemia by increasing glucose uptake through the

phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3K) and protein kinase C (PKC) pathways in

muscle. Kaempferol also decreases fasting blood glucose and HbA1c levels and

increases insulin resistance.

Consumer Considerations

Currently,

California produces 75% of the stalk celery crop in the United States, followed

by Florida, Texas, and Michigan.9 Celery is cultivated extensively

in India, France, and the United States for its seed. In India, 40,000 tons of

celery is grown annually, much of it for seed, which is exported to American

and European markets.3,9 For seed production, large-scale

cultivation of celery is required. When seed heads are ripe, celery plants are

cut and left to dry in the field for two to three days before threshed for

seeds. Average yield of celery seed cultivation is approximately one ton per hectare.12

Celery

generally is safe for common consumption. However, type 1 (IgE-mediated) allergic

reactions to celery upon ingestion are common among those allergic to birch (Betula spp., Betulaceae) pollen as well

as  in central European populations.8,10 Celery root which contains xanthotoxin

(methoxsalen, 8-methoxypsoralen) and 5-methoxypsoralen and the allergen

profilin (Api g 1), which shows strong similarities to birch pollen profiling.8

Additionally, those that are allergic to mugwort (Artemisia spp., Asteraceae) pollen frequently have allergic

reactions to celery and other Apiaceae plants. This is known as

“celery-mugwort-spice-syndrome” which was documented in 31 patients (27 females

and four males) between 1978 and 1982.22 Subsequent skin and radioallergosorbent

tests (RAST) revealed that 87% of patients that were allergic to celery had

pollinosis in the form of mugwort pollen sensitization.23 In

sensitive individuals, allergic reactions may include anaphylaxis.8,23

Celery may cause cross-reactivity (cross-allergenicity) between cucumber (Cucumis sativus, Cucurbitaceae), carrot,

watermelon (Citrullus lanatus,

Cucurbitaceae), and possibly apples (Malus

spp., Rosaceae).8 in central European populations.8,10 Celery root which contains xanthotoxin

(methoxsalen, 8-methoxypsoralen) and 5-methoxypsoralen and the allergen

profilin (Api g 1), which shows strong similarities to birch pollen profiling.8

Additionally, those that are allergic to mugwort (Artemisia spp., Asteraceae) pollen frequently have allergic

reactions to celery and other Apiaceae plants. This is known as

“celery-mugwort-spice-syndrome” which was documented in 31 patients (27 females

and four males) between 1978 and 1982.22 Subsequent skin and radioallergosorbent

tests (RAST) revealed that 87% of patients that were allergic to celery had

pollinosis in the form of mugwort pollen sensitization.23 In

sensitive individuals, allergic reactions may include anaphylaxis.8,23

Celery may cause cross-reactivity (cross-allergenicity) between cucumber (Cucumis sativus, Cucurbitaceae), carrot,

watermelon (Citrullus lanatus,

Cucurbitaceae), and possibly apples (Malus

spp., Rosaceae).8

Celery

roots, stems, and seeds also contain a class of phototoxic phenolic compounds

known as furanocoumarins, including psoralen, xanthotoxin, and bergapten (see

above).8 Phototoxicity has primarily been reported by those handling

fresh plants or consuming large quantities of celery root followed by exposure

to high-intensity UV radiation, such as UVA photochemotherapy or tanning

salons.23 Phototoxic reactions are not associated with consuming

celery seeds. Occasionally, furanocoumarins can cause sensitization in those

experiencing phototoxic reactions although there is no allergic mechanism

involved.24 Besides the Apiaceae, furanocoumarins are only found in

plants belonging to the mulberry (Moraceae), rose (Rosaceae), pea (Fabaceae),

and citrus (Rutaceae) families.

The

use of celery seed in concentrated herbal preparations is not recommended for

pregnant women due to its uterine stimulating properties.8,10,12,23,25

Celery seed should be avoided if there is a history of nephritis or acute

kidney inflammation due to potential irritation caused by excretion of celery’s

phthalide and other essential oil components.23,25 Celery seed may

interact with individuals taking thyroid medications, diuretics, lithium, sedatives,

or blood-thinning medications, including aspirin, clopidogrel (Plavix®)

and warfarin (Coumadin) as drug excretion may be enhanced by celery’s diuretic

properties, reducing the effectiveness of medications.25

Celery

is listed among the top 10 fruits and vegetables that frequently have the

highest pesticide residue. According to the Environmental Working Group’s

annually published research on detectable pesticide residues on fresh produce,

more than 95% of samples of conventionally grown celery tested positive for

pesticides.26 For children, the elderly, or those with compromised

immune systems, it is recommended to choose celery that has been organically

grown.6 If the celery is not organically grown, recent study

indicate that rinsing produce in a 10% salt water solution was significantly

more effective at removing pesticides than plain water. However, mixing one ounce

of baking soda with 100 ounces of water was most effective at removing

pesticide residues on the surface of crops.27

Nutrient Profile28

Macronutrient Profile: (Per 100 grams raw

celery [approx. 1 cup, chopped])

14 calories

0.7 g protein

3 g carbohydrate

0.2 g fat

Secondary Metabolites: (Per 100 grams raw

celery [approx. 1 cup, chopped])

Very good source of:

Vitamin

K: 29.3 mcg (24.4% DV)

Good source of:

Folate:

36 mcg (9% DV)

Vitamin A: 449 IU (9% DV)

Potassium: 260 mg (5.5% DV)

Dietary Fiber: 1.6 g (5.3% DV)

Also provides:

Manganese: 0.1 mg (4.3% DV)

Vitamin B6: 0.07 mg (4.1% DV)

Riboflavin: 0.05 mg (3.8% DV)

Vitamin C: 3.1 mg (3.4% DV)

Calcium: 40 mg (3.1% DV)

Magnesium: 11 mg (2.6% DV)

Phosphorus: 24 mg (2% DV)

Niacin: 0.3 mg (1.7% DV)

Thiamin: 0.02 mg (1.7% DV)

Iron: 0.2 mg (1.1% DV)

DV =

Daily Value as established by the US Food and Drug Administration, based on a

2,000-calorie diet.

|

Recipe: Spanish-Style

Warm Bean and Celery Salad

Courtesy of J.

Kenji López-Alt29

Ingredients:

- 6

tablespoons extra-virgin olive oil, divided

- 2

tablespoons tomato paste (To learn more about the benefits of tomato, click here.30)

- 1

medium garlic clove, minced

- 1

medium shallot, minced (To learn more about the benefits of shallot, click here.31)

- 1/2

teaspoon smoked paprika

- 2

stalks celery, peeled and sliced on bias into 1/4-inch slices

- 1

15-ounce can large beans such as gigantes, lima beans, giant white beans, or

butter beans, drained and rinsed

- 2

tablespoons sherry vinegar

- 1/4

cup minced fresh parsley leaves

- Salt

and pepper

Directions:

- Combine

2 tablespoons olive oil, tomato paste, garlic, and shallot in a medium

skillet over medium heat, stirring constantly, until fragrant and bubbling

gently, about 2 minutes. Stir in smoked paprika and cook for 30 seconds.

- Add

celery, beans, vinegar, and remaining olive oil to the skillet and stir to

combine. Cook to warm through, about 1 minute. Stir in parsley, season to

taste with salt and pepper, and serve immediately.

|

Image credits:

All photos ©2019 Steven Foster.

Illustration is from Prof. Dr. Otto Wilhelm Thomé, Flora von Deutschland, Österreich und der Schweiz. 1885.

References

- Celery.

New World Encyclopedia website. Available at: www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Celery.

Accessed March 13, 2019.

- National Geographic Society. Edible: An Illustrated Guide to the World’s

Food Plants. Lane Cove, Australia: Global Book Publishing; 2008.

- Kooti

W, Daraei N. A review of the antioxidant activity of celery (Apium graveolens). J. Evid-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2017;22(4),1029-1034.

- Megaloudi

F. Wild and Cultivated Vegetables, Herbs and Spices in Greek Antiquity (900 B.C.

to 400 B.C.). Environmental Archaeology.

2005;10(1):73-82.

- Van Wyk B-E. Food Plants of the World.

Portland, OR: Timber Press; 2006.

- Murray M. The Encyclopedia of

Healing Foods. New York, NY: Atria Books; 2005.

- Ewbank A. Ancient Greek funerals were decked out in

celery. Atlas Obscura website. Available at: www.atlasobscura.com/articles/history-of-funeral-wreaths.

Accessed June 3, 2019.

- Tyagi

S, Chirag J, Dhruv M, et al. Medical benefits of Apium graveolens (celery herb).

Journal of Drug Discovery and Therapeutics. 2013;1(5):36-38.

- Sowbhagya

HB. Chemistry, technology, and nutraceutical functions of celery (Apium graveolens): an overview. Critical Reviews in Food Science and

Nutrition. 2012;54(3):389-398.

- Al-Asmari

AK, Athar MT, Kadasah SG. An updated phytopharmacological review on medicinal

plant of Arab region: Apium graveolens.

Pharmacognosy Reviews. 2017;11(21):13-18.

- Fazal

SS, Singla RK. Review of the pharmacognostical and pharmacological

characterization of Apium graveolens.

Indo Global Journal of Pharmaceutical

Sciences. 2012;2(1):36-42.

- Hussain

IMT, Ahmed G, Jahan N, et al. Unani description of Tukhme Karafs (seeds of Apium graveolens). International Research Journal of Biological Sciences, 2013;2(11):88-93.

- Nadkarni

AK. Apium graveolens. Volume one. Indian

Materia Medica. Bombay, India. Popular Prakashan Private Ltd.;1976.

- Pitchford

P. Healing with Whole Foods: Ancient

Traditions and Modern Nutrition. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books; 2002.

- Blumenthal M, Busse WR, Goldberg A, Gruenwald J,

Hall T, Riggins CW, Rister RS, eds. Klein S, Rister RS, trans. The Complete German Commission E Monographs¾Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. Austin, TX: American Botanical Council; Boston, MA: Integrative

Medicine Communication; 1998.

- Yusni Y, Zufry H, Meutia F, et al. The effects of

celery leaf (Apium graveolens)

treatment on blood glucose and insulin levels in elderly pre-diabetics. Saudi Medical Journal.

2018;39(2):154-160.

- Mencherini T, Cau A, Bianco G, Della

Loggia R, Aquino RP, Autore G. An extract of Apium graveolens var. dulce

leaves: structure of the major constituent, apiin, and its anti-inflammatory

properties. J Pharm Pharmacol.

2007;59(6): 891-897.

- Schlatter J, Zimmerli B, Dick R,

Panizzon R, Schlatter C. Dietary intake and risk assessment of phototoxic

furocoumarins in humans. Food Chem

Toxicol. 1991;29(8):523-520.

- Madhavi D, Kagan D, Rao V, et al. A pilot study to

evaluate the antihypertensive effect of a celery extract in mild to moderate

hypertensive patients. Natural Medicine

Journal. 2013;4(4):1-3.

- Kolarovic J, Popovic M, Mikov M, et al. Protective

effects of celery juice in treatments with Doxorubicin. Molecules. 2009;14:1627-1638.

- Zidorn C, Johrer K, Ganzera M, et al.

Polyacetylenes from the Apiaceae vegetables carrot, celery, fennel, parsley,

and parsnip and their cytotoxic activities. Journal

of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2005(53):2518-2523.

- Wüthrich,

Brunello & Hofer, T. (1984). Food allergy: The 'celery-mugwort-spice

syndrome' - associated with mango allergy?. Deutsche

medizinische Wochenschrift. 1984

Jun 22;109(25):981-986.

- Gardner Z, McGuffin M. American Herbal Products Association’s Botanical Safety Handbook. 2nd

ed. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2013.

- Christensen LP. Polyphenols and Polyphenol-Derived

Compounds and Contact Dermatitis. Chapter 62 in Polyphenols in Human Health and

Disease. 2014;793-815. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-398456-2.00062-1

- Brinker F. Herbal

Contraindications and Drug Interactions Plus Herbal Adjuncts with Medicines. Expanded

4th ed. Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications; 2010.

- The

Dirty Dozen. Environmental Working Group website. Available at: www.ewg.org/foodnews/dirty-dozen.php.

Accessed on March 12, 2019.

- How

to Wash Vegetables and Fruits to Remove Pesticides. Food Revolution Network. https://foodrevolution.org/blog/how-to-wash-vegetables-fruits/.

Accessed on 6-5-3019.

- Basic

Report: 11143, Celery, raw. United States Department of Agriculture website.

National Nutrient Database for Standard Reference Legacy Release. April 2018.

Available at: https://ndb.nal.usda.gov/ndb/foods/show/11143.

Accessed June 7, 2019.

- López-Alt JK. Warm Spanish-Style Giant-Bean

Salad with Smoked Paprika and Celery Recipe. Serious Eats website. August 29,

2018. Available at: www.seriouseats.com/recipes/2015/02/warm-spanish-style-giat-bean-salad-recipe.html.

Accessed June 7, 2019.

- Bauman

H, Valdes G, Charles C. Food as Medicine: Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum, Solanceae). HerbalEGram. 2016;13(7).

Available at: http://cms.herbalgram.org/heg/volume13/07July/FoodAsMedicine_Tomato.html.

Accessed June 10, 2019.

- Bauman

H, Applegate C. Food as Medicine: Shallot (Allium

cepa var. aggregatum,

Amaryllidaceae). HerbalEGram. 2017;14(2). Available at: http://cms.herbalgram.org/heg/volume14/02February/FAMShallot.html.

Accessed June 10, 2019.

|