By Jenny Pereza,

Hannah Baumanb, and Becky Nicholsc

a ABC Education

Coordinator

b HerbalGram

Associate Editor

c ABC Dietetics Intern

(Texas State, 2013)

Editor’s Note: Each month, HerbalEGram highlights a conventional food and

briefly explores its history, traditional uses, nutritional profile, and modern

medicinal research. We also feature a nutritious recipe for an easy-to-prepare

dish with each article to encourage readers to experience the extensive

benefits of these whole foods. With this series, we hope our readers will gain

a new appreciation for the foods they see at the supermarket and frequently

include in their diets. We would like to

acknowledge ABC Chief Science Officer Stefan Gafner, PhD, for his contributions

to this project. The original article on watermelon was published in July 2015.

Overview

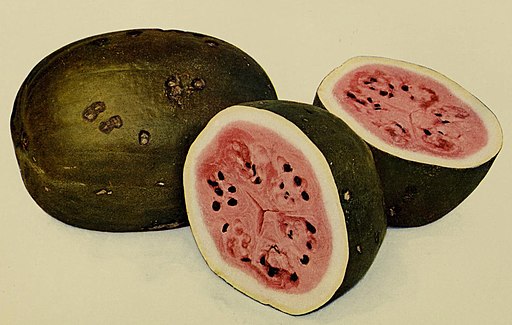

The

watermelon is a trailing annual with several firm, stout stems that grow up to 3

m (9 ft) in length with palmately lobed, hairy leaves, coiled tendrils, and

yellow monoecious (male and female) flowers.1,2 The watermelon fruit

is a very large, round-to-oblong berry with a smooth, glossy, mottled-striped skin

(rind) that is dark green to yellow in color.1,3-4 The endocarp (flesh)

of watermelons is yellowish to mostly red and contains numerous edible seeds.1,3-4

The watermelon is considered the largest edible fruit grown in the United

States; it typically weighs anywhere from a few pounds to as much as 90 pounds,

with vines that can reach up to 20 feet in length.3 Fruits must be

harvested when fully ripe and, unlike some other fruits, watermelon will not continue

to ripen when cut prematurely from the vine.1

Watermelons belong to the squash family, or Cucurbitaceae,

along with other plants that grow on vines on the ground such as cantaloupe (Cucumis

melo var. cantalupensis), pumpkin (Cucurbita pepo), butternut

squash (C. moschata), and cucumber (Cucumis

sativus). Plants belonging to the Citrullus genus

produce seeds that are distributed throughout the edible flesh, whereas close

relatives in the genera Cucurbita and Cucumis have seeds that are

located at the center of the fruit, leaving the flesh free of seeds.4

Historical and Commercial Uses

The

watermelon is native to the Kalahari Desert region in Africa and thrives in

well-draining, sandy soil.3 The wild watermelon, which is smaller,

less colorful, and more bitter-tasting than cultivated varieties, has been used

as a food and medicine in subtropical areas of Africa for more than 4,000 years.1-4

Genomic analysis  has been used to assess the relationships

among living wild and primitive watermelons from northeastern Africa, modern

sweet dessert watermelons, and other Citrullus

taxa.4 In the Kalahari Desert region, the San people use wild

watermelon (known as tsama or tsamma) as an important source of

water during the dry season.3 In earlier times, it was only possible

to travel through this region during tsama season, when wild watermelons ripened.1

The fruits of the wild Citrullus

species are small and spherical with broad, dark stripes and firm, somewhat

bitter, pale-colored, and seedy fruit flesh.4 Watermelons were not

only abundant in energy-enhancing nutrients and replenishing electrolytes, but

also a source of potable liquid in arid regions where water supplies were

questionable or polluted.5 After the juicy flesh was consumed, watermelon

gourds were often reused as canteens or for storing or even cooking berries.2 has been used to assess the relationships

among living wild and primitive watermelons from northeastern Africa, modern

sweet dessert watermelons, and other Citrullus

taxa.4 In the Kalahari Desert region, the San people use wild

watermelon (known as tsama or tsamma) as an important source of

water during the dry season.3 In earlier times, it was only possible

to travel through this region during tsama season, when wild watermelons ripened.1

The fruits of the wild Citrullus

species are small and spherical with broad, dark stripes and firm, somewhat

bitter, pale-colored, and seedy fruit flesh.4 Watermelons were not

only abundant in energy-enhancing nutrients and replenishing electrolytes, but

also a source of potable liquid in arid regions where water supplies were

questionable or polluted.5 After the juicy flesh was consumed, watermelon

gourds were often reused as canteens or for storing or even cooking berries.2

African

cuisine treats the watermelon as a vegetable and uses the entire fruit: seeds,

rinds, and flesh.6 The seeds are eaten raw or roasted as snacks

after the papery seed coat is removed. The seeds are also added to dishes,

ground into flour for use in baked goods, and used to thicken soups.2,5

In tropical western Africa, watermelon seed oil is used in cooking as a

substitute for peanut oil.5 The rind can be stir-fried, stewed,

candied, pickled, or grilled. Watermelon flesh is eaten fresh or juiced, but it

can also be fermented into wine.6

Watermelons

are among the most commonly grown annual crop in tropical and subtropical.4

Earliest records of watermelon cultivation date back to 3000 BCE, where it was depicted

in Egyptian hieroglyphics on tomb walls.3 Watermelon symbolized

nourishment and was held in such high regard that it was left as a funeral

offering for the dead in the afterlife.

As

watermelons became domesticated, cultigens with sweet, red-colored flesh were

most desirable.4 Cultigens are plants whose traits have been

deliberately altered by humans through artificial selection, resulting in

numerous cultivars or plant varieties.7 Sweet dessert watermelons

emerged approximately 2,000 years ago.4 The cultivation of

watermelon spread to China in the 10th century and to Europe, by the Moors, by

the 13th century.3 Ultimately, the watermelon crossed the Atlantic

Ocean into North America during the African slave trade.

There

are more than 50 watermelon varieties and 1,200 cultivars produced worldwide

varying in shape, color, and size.5 The four most popular cultivars

are “picnic” watermelons, which weigh between 15-50 pounds; “icebox” varieties,

designed to fit inside a refrigerator, which weigh between 5-15 pounds; as well

as “yellow-flesh” watermelons and “seedless” watermelons. When stored in a

cool, dark, or shady place, dessert watermelons can keep for weeks or even

months without significant changes in quality or taste.4

Predominately

enjoyed as a dessert, the flesh of the watermelon is eaten alone or as an

addition to fruit salads.1 In Asia and especially China, ripe

watermelon seeds are dried and roasted and enjoyed as a nutritious snack. Watermelon

juice can be made into sorbet, syrup, or wine. Although many people are

accustomed to eating the juicy flesh, the seeds and rind of watermelon are also

edible.8

China

is the largest producer of watermelon worldwide while Spain is largest producer

in the European Union.9 Turkey, Iran and the United States are also

major watermelon producers.3 The United States ranks fifth in global

watermelon production.10 Forty-four states grow watermelons,

including Texas, Florida, Georgia, and California, which collectively produce two-thirds

of all the watermelons domestically.10

Many

cultures used watermelons as a refreshing, cleansing food that was considered a

safe and dependable diuretic.5 Containing approximately 92% water, watermelon

has many traditional uses that include hydrating and moistening tissues in the

body, cleansing, eliminating impurities, and relieving inflammation.11

Ancient

Egyptians used watermelon to treat problems such as erectile dysfunction and

prostate inflammation.3 The peoples of Russia and Central Asia used

watermelon, sometimes lacto-fermented, as a diuretic and to cleanse the blood.12

Since watermelon is digested relatively quickly, the folk traditions of the

Papua New Guinea aborigines known as Onabasulu advised against eating

watermelon and other juicy fruits after a heavy meal or if suffering from a

stomachache.13

In

traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), watermelon, known as xi gua, is considered sweet, cooling, and moistening, and is used

to clear heat from the body while producing a diuretic effect.11,14 Watermelon

is used to alleviate thirst, treat edema, and reduce inflammation of the kidney

and urinary tract.11 All parts of the watermelon fruit, including

the flesh (xi gua), rind (xi gua pi), and seeds (xi gua zi), are used in TCM. Watermelon

juice is used to relieve dry conditions, such as thirst, constipation, and dehydration,

as well as hot conditions, such as summer fevers, sunburns, and canker sores.

It is also used to heal inflammation in the body.14,15 Additionally,

watermelon’s cooling properties are thought to calm irritability, restlessness,

and worry.14 This is likely attributed to watermelon’s abundant

supply of potassium and B vitamins.

Watermelon

rind is prescribed in TCM for diabetes and in cases of alcohol poisoning.2

As a traditional medicine, watermelon seed was considered more effective than

pumpkin seed oil at paralyzing and expelling tapeworms and roundworms.2

The seeds have demulcent, soothing properties and were also used to treat urinary

tract infections and bed-wetting.2

Phytochemicals and Constituents

As its name implies, watermelon is approximately

92% water. The fruit contains only 48 calories per eight-ounce serving and has a

relatively low sugar content (6%).1-3,5 Watermelons provide a good

source of B1 (thiamine), B6 (pantothenic acid), biotin,

dietary fiber, and the electrolytes magnesium and potassium.3

Watermelon

is considered a very good source of dietary antioxidants including vitamin C

and the colorful carotenoids β-carotene and lycopene.3 A one-cup

serving of watermelon provides nearly 20% of the RDI for vitamin C and almost

14% of the RDI for vitamin A due to its high β-carotene content.3

Watermelon’s high water and electrolyte content contributes to its diuretic

properties while delivering more nutrients per calorie compared to other

fruits.3

Watermelon

seeds are more nutrient dense than the flesh, containing 30-40% protein and 45%

edible oil.1,2 The seed oil is an excellent energy source for humans

and livestock, and provides linoleic, oleic, palmitic, and stearic acids.2

Watermelon seed oil has a fatty acid profile similar to pumpkin seed oil and

can be used for cooking.2 Watermelon

seeds are more nutrient dense than the flesh, containing 30-40% protein and 45%

edible oil.1,2 The seed oil is an excellent energy source for humans

and livestock, and provides linoleic, oleic, palmitic, and stearic acids.2

Watermelon seed oil has a fatty acid profile similar to pumpkin seed oil and

can be used for cooking.2

The

thick skin or rind of the watermelon has a higher content of antioxidant

phenolic acids and the amino acid citrulline than watermelon flesh.16,17

In preparing fresh cut watermelon for consumer consumption, the rind is considered

a waste byproduct despite being an abundant source of antioxidant polyphenols. The

amount of byproduct generated by processing fresh-cut watermelon is between

30-40% of the total weight.16 Research is ongoing to discover ways

in which the bioactive compounds obtained from the rind can be repurposed for

food or cosmetic uses.16

Citrulline

Citrulline

is a nonessential amino acid that was initially identified from the juice of

watermelon.15 While citrulline has been also been found in other squash

family fruits including bitter melon (Momordica

charantia, Cucurbitaceae), cucumber, cantaloupe, and pumpkin, watermelon is

the richest known source of citrulline.16,17 Considered to be a

major hydroxyl radical scavenger, citrulline content is highest in the wild

watermelon, where its potent antioxidant ability is thought to impart drought tolerance.

Citrulline

is a precursor to the amino acid arginine and is involved in the urea cycle, removing

nitrogen and other toxic compounds the blood and eliminating them through

urine.16,17 Because arginine is involved in maintaining the health

of numerous body systems, citrulline is of increasing scientific interest.9

Renal failure is often associated with impaired citrulline metabolism.17

Up to 83% of citrulline can be converted to arginine in the kidneys. Arginine

is an essential amino acid that the body uses to make protein, boost muscle

growth, reduce fat accumulation, improve insulin sensitivity, enhance wound

healing, and stimulate the immune system.16,17

Arginine

is the precursor to forming nitric oxide (NO) in the body, a potent vasodilator

that helps maintain a healthy cardiovascular (CV) system. Nitric oxide can

lower resting blood pressure and increase muscle contractility, muscle blood

flow, peripheral vasodilation, and glucose uptake in skeletal muscles.18-20

Conditions such as cardiovascular diseases, erectile dysfunction, and headaches

may benefit from enhanced vasodilation via increased arginine intake.16

Citrulline’s antioxidant properties coupled with its ability to generate NO

make it an important option for the treatment of health conditions

characterized by oxidative stress and decreased arginine availability.16,17,20

Evidence

from several studies suggests that middle-aged and older adults with CV risk

factors and CV disease experienced an improvement in endothelial function when

supplementing with L-citrulline for 1-8 weeks. Doses varied from 2.4 g up to 6 g

daily.19 Both L-citrulline and watermelon supplementation improve

blood levels of both L-arginine and NO.

Lycopene

Though

the tomato (Solanum lycopersicum,

Solanaceae) is better known as a source for lycopene (and, in fact, its

name is derived from lycopersicum), this red-pigmented phytochemical

gives fruits like watermelon, papaya (Carica papaya, Caricaceae), and pink grapefruit (Citrus

× paradisi, Rutaceae)

their color.21 Lycopene is fat-soluble and concentrated in the

liver, adrenal glands, prostate gland, and fat tissue. It is considered to have

more antioxidant power than both β-carotene (provitamin A) and α-tocopherol

(vitamin E).22

The

lycopene contained in most foods has a 40-50% cis-isomer configuration, reducing bioavailability.22

For example, the heat processing of tomatoes induces isomerization of lycopene

from all-trans to cis configuration, which converts

lycopene into a highly bioavailable form with the help of carotenoid isomerase

enzyme.22,23 Watermelon actually lacks the carotenoid isomerase

enzyme and, therefore, is the only known fruit that contains lycopene in an

all-cis configuration, making dark,

red-fleshed, fresh watermelon one of our greatest sources of readily

bioavailable dietary lycopene.16,23

Studies

indicate that watermelon juice consumption increases blood levels of both

β-carotene and lycopene.14 Unlike other carotenoids, such as β-carotene

that are provitamin A, lycopene lacks a β-ionone ring structure and cannot be

converted into vitamin A. Therefore, lycopene’s biological effects are

attributed to mechanisms other than vitamin A.22 In vitro studies

have discovered that lycopene’s non-oxidative mechanisms include its ability to

regulate gap-junction communication, regulate gene function, modulate

cytochrome P450 in the liver, and can enhance phase II drug metabolism and as

such enhance elimination of undesirable substances (e.g., certain carcinogens).22,23

Modern

Research and Potential Health Benefits

The

traditional uses for watermelon as a medicine are beginning to gain scientific support,

particularly in regard to its applications against oxidative stress, erectile

dysfunction, weight management, and kidney disease. Watermelon’s antioxidant

and nutrient content defends against many different conditions. Evidence from

epidemiological studies indicate that consumption of watermelon and other foods

rich in lycopene is strongly associated with a lower incidence of

cardiovascular disease as well as certain types of kidney and prostate cancers.16

Anti-aging

and Oxidative Stress Reduction

Oxidative

stress is thought to be at the root of many chronic diseases such as

atherosclerosis, diabetes, cancer, and cataracts. Production of free radicals

naturally occurs as byproducts of the body’s metabolic processes. However, poor

diet and an unhealthy lifestyle can overwhelm the body’s detoxification

processes, resulting in chronic inflammation. Consuming a diet rich in fruits

and vegetables plays a significant role in protecting cells from DNA damage.

Lycopene can restore antioxidant enzymes, including glutathione peroxidase and

superoxide dismutase, while decreasing lipid peroxidation, which is one of the

leading factors leading to atherosclerosis.23

Skin

is the largest organ in the human body and is most susceptible to damage due to

the sun’s UV rays, including wrinkles, freckling, sun burn, and skin cancer.24

Diets rich in colorful carotenoid compounds are directly related to skin

health. Studies indicate an inverse correlation with the consumption of eggs

and green leafy vegetables and the occurrence of wrinkles on the skin. Foods

rich in carotenoids, such as β-carotene and lycopene, are some of the most

efficient singlet oxygen quenchers. Recently, dietary carotenoids have been evaluated

for use as natural photo-protective substances. Carotenoid concentrations in

the skin vary by location on the body (forehead > palm > dorsal > inside

arm = back of hand). The skin protecting benefits of carotenoids can be

amplified through both oral and topical supplementation. Compared to topical

sunscreens which require reapplication and have localized antioxidant effects,

UV protection, studies indicate that the use of carotenoid-rich foods or

natural products prior to and during sun exposure appears to be a systemic way

of boosting blood and skin levels of these highly antioxidant carotenoids, thus

reducing sunburn and skin damage.

Cardiovascular

Health

Several

studies have confirmed that watermelon offers cardiovascular benefits in a

variety of ways. Watermelon is a great source of electrolytes, including potassium

and magnesium, as well as citrulline. It also contains the most bioavailable

form of lycopene. All of these compounds are involved in modulating blood

pressure.20,25 In addition to being an antioxidant, lycopene has

been shown to be heart-protective and has been linked to a reduction in high

cholesterol and other risk factors that can lead to cardiovascular disease.26

Current

research shows that citrulline in watermelons improves cardiovascular health by

increasing the  bioavailability of arginine, which subsequently increases the

synthesis of NO (see above). Nitric oxide relaxes blood vessels, improves circulation

without any side effects associated with common cardiovascular medications.18

In one clinical study, obese participants with pre-high blood pressure or

stage-one high blood pressure significantly reduced their ankle and brachial

systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, and

carotid wave reflection with ingestion of 6 g citrulline powdered extract derived

from watermelons (equivalent to 2.3 pounds of fresh red-fleshed watermelon)

over a six-week period compared to placebo.27 bioavailability of arginine, which subsequently increases the

synthesis of NO (see above). Nitric oxide relaxes blood vessels, improves circulation

without any side effects associated with common cardiovascular medications.18

In one clinical study, obese participants with pre-high blood pressure or

stage-one high blood pressure significantly reduced their ankle and brachial

systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, mean arterial pressure, and

carotid wave reflection with ingestion of 6 g citrulline powdered extract derived

from watermelons (equivalent to 2.3 pounds of fresh red-fleshed watermelon)

over a six-week period compared to placebo.27

Citrulline

content is higher and more bioavailable in watermelons that have yellow-flesh

and is more effective than supplementation with arginine itself because

citrulline bypasses the liver and is not a substrate for arginase.17,28

As a supplement, L-citrulline is better tolerated than L-arginine, which causes

gastrointestinal side effects as high doses (more than 10 g).17 Dietary

supplements containing citrulline are being used to improve sexual stamina and

erectile dysfunction, however the mechanism of action is not clear.28

Anti-fatigue

and Ergogenic Aid

The

use of watermelon juice (500 mL) or L-citrulline powder (~ 6 g) has gained

popularity as an ergogenic aid to exercise training.19,20 Human

studies have been conducted to assess the effects of citrulline supplementation

by athletes. The use of citrulline from watermelons can improve athletic

performance primarily due to its ability to increase glucose transport in

skeletal muscle as well as its use in NO synthesis. Citrulline has also been

shown to accelerate the removal of lactic acid, a major contributor of muscle

soreness and fatigue, allowing for more intense training and faster recovery

after workouts.20 Watermelon’s potassium and magnesium content also

help the body recover lost electrolytes, relieve muscle cramping and maintain

normal muscle and nerve function.10

A

100-g serving of watermelon contains 160 mg of citrulline.21 When

ingested prior to exercise, citrulline can reduce the accumulation of lactic

acid in skeletal muscles by accelerating metabolism of lactate; detoxify

ammonia and other harmful metabolites of the urea cycle in the liver; and

increase ATP production in muscles, which increases muscle strength. Citrulline

is more bioavailable when delivered in a natural matrix, such as unpasteurized

watermelon juice, or fresh watermelon. Regardless of whether the watermelon

juice was enriched with additional L-citrulline, studies have confirmed there

is a significant reduction in muscle soreness when compared with placebo.20

Diabetes

and Weight Management

Watermelon consumption has been evaluated for its

effectiveness in glycemic control, weight management, and circulatory problems

common in diabetics. Replacing conventional snacks with watermelon increases

potassium intake as well as lipid-lowering phytonutrients.29 To

determine the effects of daily watermelon consumption, 20 overweight and obese

adults participated in a four-week repeated-measures crossover study with two

treatments: 2 cups freshly diced watermelon as daily snack in addition to

regular diet, followed by a 2-4 week washout period, then crossed over to an

iso-calorically matched low-fat cookie snack. After four weeks of low-fat

cookie consumption, blood pressure, blood lipids, body weight, and BMI

increased; after four weeks of watermelon snack consumption, these parameters

decreased. Additionally, those consuming whole watermelon fruit snack

experienced a greater feeling of fullness and felt less hungry for up to two

hours afterwards.

In addition to its fiber content, watermelon

consumption is associated with higher levels of adiponectin, a protein hormone

involved in regulating blood glucose levels as well as the breakdown of fatty

acids (FAs), which could account for its satiating effects.29

Watermelon’s ability to lower blood pressure is attributed to the presence of

citrulline. Improvement in blood lipid profiles was attributed to watermelon’s

β-carotene and lycopene content. Due to lycopene’s lipophilic nature,

excess can be stored in adipose tissue.23 Lycopene also improves

insulin sensitivity and glucose metabolism.

Cancer Preventive Effects

Lycopene’s

powerful antioxidant properties have been shown to reduce the risks of

prostate, lung, gastric, and colorectal cancers.26,30 Lycopene

reduces the production of pro-inflammatory mediators including interleukins, NO,

and tumor necrosis factor alpha thus preventing inflammation. However, due to

its antioxidant effect it seems to interfere with chemo and radiation therapy.

Research interventions have observed an inverse

correlation between the consumption of lycopene-rich foods and prostate cancer.23

Men consuming a lycopene-rich diet reported 25% lower incidence of prostate

cancer and a 44% reduced risk of other cancers. Likewise, females consuming

watermelon on a regular basis are five times less likely to develop cervical

cancer.

Consumer

Considerations

When selecting watermelons, consumers should look

for fruits with smooth skin and a cream-colored underside.3 When

cut, a ripe watermelon will have firm, juicy flesh and dark brown to black

seeds. Watermelon is considered immature if there are white streaks in the

flesh or if there are white seeds. Like most melons, watermelons spoil easily

if they are not kept cool.8 Uncut watermelons can be kept at room

temperature for no more than two weeks.5 When possible, refrigerate

watermelons to preserve freshness, juiciness and taste.3

Melons have contact with the ground as they grow and

ripen where the skin of the fruit may come in contact with undesirable

substances.3 Before cutting into melons, it is advised to wash the

rind thoroughly with diluted, additive-free soap or a commercial produce wash

using a wet cloth or paper towel to prevent any contamination of the melon

flesh. This can also help reduce pesticide residues on conventionally grown

watermelons.

Nutrient Profile31

Macronutrient

Profile (Per

1 cup diced watermelon [approx. 152 g]):

46

calories

1

g protein

11.5

g carbohydrate

0.2

g fat

Secondary

Metabolites (Per

1 cup diced watermelon [approx. 152 g]):

Excellent

source of:

Vitamin

C: 12.3 mg (20.5% DV)

Vitamin

A: 865 IU (17.3% DV)

Very

good source of:

Potassium:

170 mg (4.9% DV)

Also

provides:

Magnesium:

15 mg (3.8% DV)

Vitamin

B6: 0.07 mg (3.5% DV)

Thiamin:

0.05 mg (3.3% DV)

Vitamin

E: 0.08 mg (3% DV)

Manganese:

0.06 mg (3% DV)

Dietary

Fiber: 0.6 g (2.4% DV)

Iron:

0.4 mg (2.2% DV)

Phosphorus:

17 mg (1.7% DV)

Folate:

5 mcg (1.3% DV)

Calcium:

11 mg (1.1% DV)

DV

= Daily Value as established by the US Food and Drug Administration, based on a

2,000-calorie diet.

|

Recipe: Pickled

Watermelon Rinds

Adapted from Bon Appétit32

For

an equally delicious condiment without the wait, use these ingredients to

make watermelon rind chutney: increase sugar to 1 ½ cups, water to 1 cup, and

finely mince the ginger. Bring all ingredients to a boil in a large pan, then

simmer for 45-60 minutes until the rind is translucent and tender and the

liquid reduces and thickens. Remove whole spices before serving.

Ingredients:

- 4

pounds of watermelon

- 1

serrano chili, thinly sliced, seeds removed if desired

- 1-inch

piece of fresh ginger, peeled and thinly sliced

- 2

star anise pods

- 1

tablespoon kosher salt

- 1

teaspoon black peppercorns

- 1

cup sugar

- 1

cup apple cider vinegar

Directions: - Using

a vegetable peeler, remove the tough green outer rind from watermelon;

discard.

- Slice

watermelon into 1”-thick slices. Cut away all but 1/4” of flesh from each

slice; reserve flesh for another use. Cut rind into 1” pieces for roughly 4

cups of rind.

- Bring

chili, ginger, star anise, salt, peppercorns, sugar, vinegar, and 1/2 cup of

water to a boil in a large, non-reactive saucepan, stirring to dissolve sugar

and salt.

- Add

watermelon rind. Reduce heat and simmer until just tender, about 5 minutes.

Remove from heat and let cool to room temperature, setting a small lid or

plate directly on top of rind to keep submerged in brine, if needed.

- Transfer

rind and liquid to an airtight container; cover and chill at least 12 hours.

|

Image

credits:

Watermelon on the vine. Image courtesy of Shu

Suehiro.

Watermelon illustration from Birds and Nature volume 15, January 1904.

Watermelon fruit. Image courtesy of Steve Evans.

References

- Van Wyk B-E. Food Plants of the World.

Portland, OR: Timber Press; 2006.

- Erhirhie

EO, Ekene NE. Medicinal values on Citrullus

lanatus (Watermelon): Pharmacological Review. International Journal of Research in Pharmaceutical and Biomedical

Sciences. 2013;4(4):1305-1312.

- Murray M. The

Encyclopedia of Healing Foods. New York, NY: Atria Books; 2005

- Paris

HS. Origin and emergence of the sweet dessert watermelon, Citrullus lanatus. Annals

of Botany. 2015;116:133-148.

- An

African Native of World Popularity. Our Vegetable Travelers. Texas

A&M University; 2000. Available here. Accessed June 22,

2015.

- Onstad

D. Whole Foods Companion: A Guide for Adventurous Cooks, Curious Shoppers &

Lovers of Natural Foods. White River Junction, VT: Chelsea Green Publishing

Company; 1996.

- AskDefine.

Define cultigen. Available here. Accessed July 17,2019.

- National

Geographic Society. Edible: An

Illustrated Guide to the World’s Food Plants. Lane Cove, Australia: Global

Book Publishing; 2008.

- Makaepea

M, Beswa D, and Jideani A. Watermelon as a potential fruit snack. International Journal of Food Properties.

2019;22(1):355-370.

- National

Watermelon Promotion Board site. Available here. Accessed June 28,

2019.

- Pitchford

P. Healing with Whole Foods: Ancient

Traditions and Modern Nutrition. Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books; 2002.

- Pieroni

A, Gray C. Herbal and food folk medicines of Russlanddeutschen living in

Kunzelsau/Talacker, south-western Germany. Phytotherapy Research.

2008;22(7):889-901.

- Meyer-Rochow

V. Food taboos: their origins and purposes. Journal of Ethnobiology and

Ethnomedicine Online. 2009;5(18):1-10.

- Chinese Medicine Nutrition: Benefits of

Watermelon. AOMA Graduate School of Integrative Medicine. Available here.

Accessed June 23, 2019.

- Watermelon Juice: Summer’s Superfood.

Traditional Chinese Medicine World Foundation. Available here.

Accessed July 10, 2019.

- Tarazona-Diaz M, Viegas J, Moldao-Martin

M, Aguayo E. Bioactive compounds from flesh and by-product of fresh-cut

watermelon cultivars. Journal of Science

and Food Agriculture. 2011;91:805-812.

- Bahri

S, Zerrouk N, Aussel C, Moinard C, et al. Citrulline: from metabolism to

therapeutic use. Nutrition. 2013;

29(3):479-484.

- Martinez-Sanchez

A, Ramos-Campo D, Fernandez-Lobato B, et al. Biochemical, physiological, and

performance response of a functional watermelon juice enriched in L-citrulline

during half marathon race. Food &

Nutrition Research. 2017;61:1-12.

- Figueroa

A, Wong A, Salvador J, et al. Influence of L-citrulline and watermelon

supplementation on vascular function and exercise performance. Current Opinion Clinical Nutrition Metabolic

Care. 2017;20(1):92-98.

- Tarazona-Diaz

M, Alacid F, Carrasco M, et al. Watermelon juice: potential drink for sore

muscle relief in athletes. Journal of

Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2013;61:7522-7528.

- Wahyuni

Islah. Antifatigue activity of Citrullus (Citrullus lanatus) genus

plants: a review. The 1st Payung Negeri

International Health Conference. Conference Paper. 2019;57-70.

- Gajowik

A and Dobrzynska M. Lycopene – antioxidant with radioprotective and anticancer

properties: a review. National Institute

of Public Health – National Institute of Hygiene. 2014;65(4):263-271.

- Naz

A, Butt MS, Sultan MT, et al. Watermelon lycopene and allied health claims. Experimental and Clinical Sciences Journal.

2014;13:650-666.

- Evans

J and Johnson E. The role of phytonutrients in skin health. Nutrients. 2010;2:903-928.

- Massa

NM, Silva AS, Toscano LT, et al. Watermelon extract reduces blood pressure but

does not change sympathovagal balance in prehypertensive and hypertensive

subjects. Blood Pressure.

2016;25(4):244-248.

- Seren

S, Liberman R, Bayraktar U, et al. Lycopene in cancer prevention and treatment.

American Journal of Therapeutics. 2008;15(1):66-81.

- Figueroa

A, Sanchez-Gonzalez M, Wong A, Arjmandi B. Watermelon extract supplementation

reduces ankle blood pressure and carotid augmentation index in obese adults

with prehypertension or hypertension. American Journal of Hypertension.

2012;25(6):640-643.

- Rimando

AM and Perkins-Veazie PM. Determination of citrulline in watermelon rind. Journal of Chromatography.

2005;1078:196-200.

- Lum

T, Connolly M, Marx A, et al. Effects of fresh watermelon consumption on acute

satiety response and cardiometabolic risk factors in overweight and obese

adults. Nutrients. 2019;11:595-608.

- van

Breemen RB, Pajkovic N. Multitargeted therapy of cancer by lycopene. Cancer

Letters. 2008;269(2):339-351.

- Basic

Report: 09326, Watermelon, raw. Agricultural Research Service, United States

Department of Agriculture website. Available here. Accessed June 22,

2015.

- Pickled

Watermelon Rind. Bon Appétit. August 2014. Available here. Accessed June 22,

2015.

|