|

Editor’s Note: Each month, HerbalEGram highlights a conventional food and

briefly explores its history, traditional uses, nutritional profile, and modern

medicinal research. We also feature a nutritious recipe for an easy-to-prepare

dish with each article to encourage readers to experience the extensive

benefits of these whole foods. With this series, we hope our readers will gain

a new appreciation for the foods they see at the supermarket and frequently

include in their diets.

We would like to acknowledge ABC Chief

Science Officer Stefan Gafner, PhD, and HerbalGram Associate Editor Hannah Bauman for their contributions to this project.

By Jenny

Perez, ABC Education Coordinator

Overview

Rosaceae

is one of the largest and most economically important fruit- and

berry-producing plant families and contains approximately 430 Prunus species, known as stone fruits.1

The term “stone fruit” is synonymous with drupe, which refers to fruits with

only one large seed surrounded by the hardened endocarp beneath the skin

(exocarp) and juicy flesh (mesocarp).1,2 Commonly consumed stone

fruit species include peach (Prunus

persica), cherry (P. avium and P. cerasus), apricot (P. armeniaca), and plum (P. domestica and P. salicina), among

others.1 This article will focus on P. domestica, commonly

known as the European plum. Rosaceae

is one of the largest and most economically important fruit- and

berry-producing plant families and contains approximately 430 Prunus species, known as stone fruits.1

The term “stone fruit” is synonymous with drupe, which refers to fruits with

only one large seed surrounded by the hardened endocarp beneath the skin

(exocarp) and juicy flesh (mesocarp).1,2 Commonly consumed stone

fruit species include peach (Prunus

persica), cherry (P. avium and P. cerasus), apricot (P. armeniaca), and plum (P. domestica and P. salicina), among

others.1 This article will focus on P. domestica, commonly

known as the European plum.

Plum

trees prefer moist, well-drained soils and are cultivated widely due to their adaptability

to a wide range of climate conditions.1,2 Plum trees grow 20-30 feet

tall and have dark green, simple, ovate leaves with serrated margins and white

flowers that appear singly, in pairs, or in small clusters.3-5 There

are more than 40 species and 2,000 varieties of plum, all of which have a

characteristic crease running down one side of the fruit. The fruits are round

to oval in shape, contain a single smooth seed, and have a smooth, waxy layer

and deeply pigmented skin in hues of red, purple, indigo, yellow, or green.1,6-8

The two primary plum species of commercial significance worldwide are European

plum and Japanese plum (P. salicina).

The fruits are the distinguishing feature of these two species: European plums

are small and oval-shaped, with thicker, firmer flesh that is purple to red in

color and a pit that is easy to remove, while Japanese plums are larger, round,

and juicy, with yellow to red skin.3 European plums have a high

sugar content and are mainly grown for processing into dried plums, also known

as prunes.2,4,7,9

Historical and Commercial Uses

The

common European plum is regarded as an ancient cultigen derived from cherry

plum (P. cerasifera) and possibly sloe

(P. spinosa) or the damson plum (P. insititia).4 Approximately

2,000 years ago, European plums originated in western Asia near the Caucasus Mountains

and Caspian Sea.2,5,7 According to Greek writers,  cultivated plums originally

were imported to Greece from Syria. The Romans later brought P. domestica to western Europe.6

In the 12th century, Crusaders brought plum trees back from their journeys in

Syria. In the 17th century, Spanish missionaries and English colonists brought

European plums to North America.5,7 cultivated plums originally

were imported to Greece from Syria. The Romans later brought P. domestica to western Europe.6

In the 12th century, Crusaders brought plum trees back from their journeys in

Syria. In the 17th century, Spanish missionaries and English colonists brought

European plums to North America.5,7

Both

juicy and sweet, plum fruits are eaten fresh or used in jams, desserts, and

side dishes.1,4 Plum puree is used as a substitute sweetener, adding

moisture and dark color to baked goods, and it can improve flavor and help

pre-cooked meats retain moisture.9,10 Dehydrating fresh European plums

for 18 hours at 85-90°C is a traditional preservation technique developed near

the Caspian Sea, where the European plum was eaten as a wild-harvested food.2,4,7

European plum varieties have a natural sugar content that allows them to be

dried, with the pit intact, without fermenting. Prunes are commonly studied as

a functional food with therapeutic benefits.

In eastern

Europe, plum juice is fermented into plum wine, which, when distilled, produces

a brandy known as slivovitz, rakia, tuică, or pálinka.1 In Serbia,

plum production averages 424,300 metric tons annually. Szabolcs-Szatmár-Bereg,

Hungary, near the border of Ukraine and Romania, is the region that produces

the most plums. In Hungary, plums are called szilva and are made into liquor, dumplings, and a plum paste known

as lekvar. Prunes also are used in cocktail

snacks and tarts, puddings, stews, and meat dishes.4

Phytochemicals and Constituents

Prunes

are high in fiber, sugar (in the form of glucose, fructose, and sorbitol), and bone-strengthening

vitamins and minerals, including vitamin K, calcium, magnesium, potassium, boron,

and selenium.4,11,12 Calcium helps maintain bone density, and

magnesium is needed to properly metabolize vitamin D and calcium. Potassium

works synergistically with magnesium to maintain bone health, slow bone loss,

and support cardiovascular health.10 Boron and selenium are

important modulators of bone health and calcium metabolism and are key

nutrients for preserving bone mineral density.11 Vitamin K balances

calcium levels in the body and is a cofactor that promotes bone mineralization.13

Research suggests that plum’s polyphenols act synergistically with vitamin K

and potassium to aid in calcium retention and increase bone mass by slowing

down the rate of bone degradation.7,11,13

There

is a strong correlation between high dietary fiber intake and reduced incidence

of gastrointestinal (GI) conditions, such as constipation, by improving both

stool weight and GI transit time.12,14 Recommendations for daily

dietary fiber intake range from 22 to 35 g for adults.12 Prunes deliver

6 g of fiber/100 g, primarily composed of hemicellulose, pectin, and cellulose.

High-fiber diets are thought to elicit beneficial health effects through increased

stool weight, reduced GI transit time, and increased short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)

production. The high fiber content in prunes contributes to increased satiety

and can lead to lower overall calorie intake.7

Fruits

in the genus Prunus tend to be high in sorbitol, a natural sugar alcohol

that increases water volume in the intestine and contributes to the laxative

effects for which prunes and plum juice are known.10,12 Chlorogenic

and neochlorogenic acid are other components of European plums that may aid in

GI function by eliciting laxative effects and delaying glucose absorption.7,10

Sorbitol, chlorogenic acid, and neochlorogenic acid combined with the fiber

content in dried prunes hold strong potential in improving GI health and

function.

The

bone loss reversal properties of prunes may be explained by the suppression of

inflammatory pathways by plum’s abundant polyphenolic compound content (184 mg

polyphenols/100 g prunes), mainly as neochlorogenic and chlorogenic acids.10

Prunes rank higher than other commonly consumed fruits and vegetables in oxygen

radical absorbance capacity (ORAC).11 Fresh plum fruit has a greater

ability to reduce free radicals than its dried counterpart.7 Prunes

contain higher levels of phenolic compounds than most fruits. The

bone loss reversal properties of prunes may be explained by the suppression of

inflammatory pathways by plum’s abundant polyphenolic compound content (184 mg

polyphenols/100 g prunes), mainly as neochlorogenic and chlorogenic acids.10

Prunes rank higher than other commonly consumed fruits and vegetables in oxygen

radical absorbance capacity (ORAC).11 Fresh plum fruit has a greater

ability to reduce free radicals than its dried counterpart.7 Prunes

contain higher levels of phenolic compounds than most fruits.

Although

no clinical trials have been conducted on plum polyphenols to date, the

phenolic compounds present in plums appear to improve cognition, especially

spatial memory and learning, as well as reduce age-related cognitive deficits and

the occurrence of beta-amyloid plaques.7 Additionally, plum’s chlorogenic

acid content is associated with anxiety-relieving effects. These polyphenolic

compounds have also been recognized as key constituents that can reduce high

cholesterol levels as well as the incidence of atherosclerosis because of

anti-inflammatory and anti-hypertensive effects.

In

vitro studies have demonstrated several potential mechanisms by which prunes

affect bone metabolism. Polyphenols in prunes protect bone by scavenging free

radicals and preventing oxidative damage.11 Although exact

mechanisms have not yet been determined, research findings indicate that prunes

modulate osteoblast (bone formation) and osteoclast (bone resorption) activities

by increasing blood levels of bone-specific alkaline phosphatase (BAP) and insulin-like

growth factor 1 (IGF-1).15 The bone-building effects of prunes are dose-dependent

and can be enhanced with the concomitant use of fructooligosaccharides (FOSs),

which are known to enhance mineral absorption in the large intestine and help restore

bone mass and quality after bone loss has already occurred.16 Compared

with parathyroid hormone, a common anabolic therapy prescribed to increase bone

formation, prune supplementation has been shown to inhibit bone turnover and

have a positive effect on bone mass and bone structure without serious adverse

effects.7 The most commonly experienced adverse effects of prune

consumption include an increase in bowel movement frequency and softer stool

consistency, often accompanied by flatulence and mild gastric discomfort.7,12

While potentially inconvenient, these side effects are not as serious as those

associated with common osteoporosis-preventing drug therapies.

Modern Research and

Potential Health Benefits

Research

on the dietary use of European plum and its associated products has focused on

potential anti-allergic properties, cardiovascular support, cognitive function,

bone health, and bowel elimination.7 The majority of clinical trials

used prunes rather than fresh fruit.7 The greatest amount of clinical

evidence for plum’s potential health benefits involves the prevention and

management of osteoporosis and improving bowel elimination.

Effects on Bone Health

According

to the 2015-2020 Dietary Guidelines for Americans, average fruit intake by men

and women is well below recommended amounts, with the exception of children

between the ages of 1 and 8.8 Girls between the ages of 14 and 18 and

women 51 years and older are reported to have the lowest average fruit intake,

coinciding with two critical periods of time for bone development and

maintenance. Accelerated bone loss occurs in postmenopausal women when ovarian

hormones, primarily estrogen, are no longer produced by the body.16 During

the first 10 years from the onset of menopause, women can lose up to 50% of

their trabecular bone and 30% of cortical bone (compact, dense outer surface of

bone).13 A reduction in bone density is a major risk factor for

osteoporosis, a chronic condition associated with an increase in bone fragility

and fractures.7,16

Aside

from drug therapies, including hormone replacement therapy (HRT), which has

negative side effects and high costs, lifestyle and nutrition can play a large

part in reducing the risk of osteoporosis.15 From a nutritional

aspect, research has shown that specific foods have bone-protective effects. Examples

include soybeans (Glycine max,

Fabaceae), flaxseeds (Linum usitatissimum,

Linaceae), and plums. Several studies have demonstrated that prunes have more potent

bone-protective effects than other dried fruits (apple [Malus spp.,

Rosaceae], apricot, grape [Vitis vinifera, Vitaceae], and mango [Mangifera indica, Anacardiaceae]) and can prevent or reverse age-related bone

loss and bone fragility common in postmenopausal, osteopenic women.16 and high costs, lifestyle and nutrition can play a large

part in reducing the risk of osteoporosis.15 From a nutritional

aspect, research has shown that specific foods have bone-protective effects. Examples

include soybeans (Glycine max,

Fabaceae), flaxseeds (Linum usitatissimum,

Linaceae), and plums. Several studies have demonstrated that prunes have more potent

bone-protective effects than other dried fruits (apple [Malus spp.,

Rosaceae], apricot, grape [Vitis vinifera, Vitaceae], and mango [Mangifera indica, Anacardiaceae]) and can prevent or reverse age-related bone

loss and bone fragility common in postmenopausal, osteopenic women.16

In

a randomized controlled trial designed to measure the effects of prune

consumption on bone turnover markers, 58 postmenopausal women were randomly

assigned to a three-month dietary intervention trial to either a group that consumed

100 g prunes (approximately 12 prunes) daily or a group that consumed 75 g

dried apple daily as part of their routine diets.11 The amount of prunes

and dried apple consumed provided similar calories, fat, carbohydrates, and

fiber. Blood and urine samples taken at baseline and post-treatment showed that

only the prunes significantly increased (P < 0.01) IGF-1, which

enhances osteoblastic activity and bone formation. There is a positive

correlation between IGF-1 values and bone mass in premenopausal, perimenopausal,

and postmenopausal women. While prune supplementation increased markers of bone

formation, it didn’t affect bone resorption markers compared to baseline. Additionally,

BAP activity, which is associated with higher rates of bone formation, increased

by 5.8% over baseline in the treatment group, indicating a comparatively rapid

increase in bone formation after only three months of regular prune consumption.

Researchers predict that BAP activity would continue to rise with longer-term

supplementation and may become clinically superior to standard bone-forming

medications such as sodium fluoride and parathyroid hormone, which take several

months to moderately increase BAP activity.7,11 Unlike soybean

supplementation, prunes did not produce any estrogenic effects assessed by

circulating hormone levels and maturation index.11

In a

similar randomized controlled trial, 160 postmenopausal women with osteopenia

were randomly assigned to either a prune group (dose 100 g daily) or dried

apple group (75 g) as an active control for a 12-month period.13 Additionally,

all participants were given 500 mg supplemental calcium and 400 IU of vitamin

D, standard nutritional supplements taken for bone health. At baseline, three, six,

and 12 months, bone mineral density (BMD) in total body, lumbar, forearm, and hip

was measured. At the same intervals, blood samples were collected and analyzed

for changes in the values of key bone health biomarkers, including IGF-1, BAP,

and high-sensitivity C-reactive protein (hs-CRP). Results demonstrated a

significant increase in BMD compared to the control group.7,16

The

same researchers conducted a study on osteopenic postmenopausal women to

determine the extent that a lower prune dose (50 g daily) would have on

preventing loss of BMD. In this clinical trial, 48 postmenopausal women between

the ages of 65 and 79 with osteopenia were randomly assigned to one of three

treatment groups for six months: (1) 50 g per day of prunes (approximately 5-6 prunes);

(2) 100 g per day of prunes; and (3) a control group with no prune supplementation.15

As in the previous trial, all participants received 500 mg of calcium carbonate

and 400 IU of vitamin D supplementation daily. Blood values of BSAP, IGF-1, hs-CRP,

and other bone health biomarkers were measured at baseline, three months, and six

months. Total body, hip, and lumbar BMD were recorded at baseline and six months.

Results confirmed that both doses of prunes (50 g daily as well as 100g daily) prevented

the loss of total body bone mass density (BMD) compared to the control group. (P

> 0.05).15 This was attributed, in part, to the ability of prunes

to inhibit bone resorption. Based on the data, researchers suggest that in

addition to the concurrent supplementation of vitamin D and calcium, the lower

(50 g) dose of prunes appears to be as effective as a 100 g dose in preventing

bone loss in older, postmenopausal women with osteopenia.

Another

area of promise is the use of prune in the diet to build bone and improve

skeletal health in breast cancer patients post radiation exposure or

chemotherapy as well as astronauts exposed to space radiation while on the International

Space Station.18 These types of ionizing radiation increase the

production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) by marrow cells and inhibits

cellular repair, potentially damaging DNA.17 Other unfavorable side

effects include a decrease in BMD and lean body mass and elevated inflammation

markers.18

In an

RCT, postmenopausal women who completed breast cancer treatments at least six

months prior to the trial participated in a study investigating the effects of prune

consumption, in addition to resistance training, on strength, body composition,

bone biomarkers, and inflammation markers. The 23 patients who completed the

study were evaluated at baseline and after the six-month mark for changes in

muscular strength, body composition (specifically BMD), bone turnover rates,

and inflammation levels.18 Participants were randomly assigned to a

resistance training (RT) only group or a RT plus prune consumption group. In

addition to the exercise regimen, the active treatment group consumed three 30g

packets of prunes daily, delivering between 84-96 g from approximately 9-12 prunes.

At six months, the results showed that BMD was maintained with a decline in

bone resorption in the treatment group. Inflammation biomarkers also declined,

though the decrease was not statistically significant and there was no additive

effect of prune consumption to RT over the duration of the study. Unfortunately,

the design of the study did not include a prune consumption only group, which

is necessary to assess whether daily prune consumption alone would have similar

BMD and biomarker changes in bone turnover and inflammation as reported in

postmenopausal patients.

While

many of these clinical studies had several limitations and inconsistent

results, outcomes suggest that postmenopausal women who consume prunes as part

of daily recommended fruit intake can benefit from their bone-protective

properties.8 Researchers suggest that long-term prospective cohort

studies using fractures and BMD as the primary endpoints are needed to confirm

the potential effects of prune consumption.8 Additionally, in order

to make generalizable dietary recommendation of prune consumption, future

clinical studies should include premenopausal women, men, and adolescents prior

to reaching peak bone mass. Overall, the clinical studies in postmenopausal

women and breast cancer survivors that have been conducted thus far suggest a

potential increase in BMD via modulation of bone formation and bone resorption,

suppression of bone turnover rates, and reduction of inflammatory-inducing CRP

levels.13,15,18

Laxative Effects

GI

tract diseases and functional disorders, such as colorectal cancer,

diverticulitis, hemorrhoids, and constipation, are most common in developed

countries and associated with the Standard American Diet (SAD).12

The SAD is low in fruit and vegetable intake and thus highly deficient in

dietary fiber resulting in low stool weight and delayed GI transit time,

important risk factors in developing GI tract disorders and diseases.12,14

Epidemiological evidence shows that the majority of GI disorders are

preventable. Due to limited training by medical doctors on dietary management

of functional GI disorders, like constipation, there is an overreliance on

pharmaceutical fiber supplements and over-the-counter laxatives.14 Individuals

with constipation commonly experience symptoms including straining to defecate

and incomplete evacuation.

There

is sufficient clinical evidence that consuming prunes improves GI health and bowel

elimination. This is attributed to synergistic effects of plum’s polyphenol,

fiber, and sorbitol content.7 In multiple clinical studies, patients

with mild to moderate constipation who consumed prunes daily experienced

improved elimination, softened stools, and relief of constipation.7

In an

effort to improve study quality and applicable outcomes, Lever et al. conducted

an RCT to investigate the effects of dose-dependent prune consumption on stool

output, whole gut transit time, gut microbiota, and SCFA production. In this

single center, three-arm parallel group clinical trial, 120 healthy adults

ranging from 18 to 65 years of age who consumed a low fiber diet and experienced

low stool frequency (3-6 stools per week), participated in a nine-week study.

After a one-week period in which baselines were measured, participants were

randomly assigned to one of three groups: (1) 80 g prunes taken with 10 ounces

of water daily; (2) 120 g prunes taken with 10 ounces of water daily; and (3) 10

ounces of water daily but no prunes (control group).12 For

participants consuming prunes, there were statistically significant results for

improved stool frequency (P = 0.023) and stool weight (P = 0.026).

There were no significant differences in fecal microbiota or absolute values of

SCFA compared to baseline. However, both plum groups had higher levels of

bifidobacteria in the large intestine, which is associated with the prevention

and treatment of constipation, inflammatory bowel disease, and colorectal

cancer.

Consumer Considerations

Today,

the primary producers of plums grown commercially are the United States,

Serbia, China, and Romania.7,8 In 2016, 135,000 tons of fresh plums

from 18,700 acres were produced in the United States.9 The state of

California produces 54,000 tons of plum annually, accounting for 99% of the

plums produced in the United States and 67% of the world’s prune supply.7-9

Pediatricians

often advise parents to use prune puree and prune juice to relieve infant

constipation.10 Prunes and prune juice are similarly used by adults

and the elderly who have low fiber diets or are prone to sluggish bowel

elimination. It is worth noting that moderate consumption of prunes (6-12

daily) does not produce excessive laxative effects.

In

addition to consuming five to nine servings of fruits and vegetables daily, a

standard serving of five prunes (approximately 40 g) or eight ounces of prune

juice can be a healthy addition to the diet of all age groups, especially women

over 40 years of age.10 A 100 g serving of prunes (approximately 12 prunes)

will deliver 20% of the recommended daily intake (RDI) for potassium and

copper, 14% iron, and 10% magnesium and zinc. Eight ounces of prune juice will

deliver 20% RDI for magnesium and zinc as well as 10% RDI for magnesium and

copper. Given its nutrient profile and promising clinical evidence, there is

sufficient evidence to support the reputation of prunes as an important

functional food that can easily be integrated into the diet to support bone

health and GI function.

There

are no known serious side effects associated with consuming plums or its

products. Additionally, long-term dietary use of prunes has no significant

effect on insulin or glucose levels.7,10 However, plums contain

moderate amounts of oxalates, which bind with calcium in the body, reducing

absorption while forming calcium oxalates that may increase kidney or bladder stone

formation in those individuals with a predisposition to developing stones.7

Nutrient Profile: Prune19

Macronutrient Profile: (Per 100 g;

approximately 12 prunes)

240 calories

2.18

g protein

63.9 g carbohydrate

0.38

g fat

Secondary Metabolites: (Per 100 g;

approximately 12 prunes)

Excellent source of:

Vitamin

K: 59.5 mcg (49.6% DV)

Dietary

Fiber: 7.1 g (23.7% DV)

Copper:

0.28 mg (31% DV)

Very good source of:

Potassium:

732 mg (15.6% DV)

Riboflavin:

0.19 mg (14.6% DV)

Manganese:

0.3 mg (13% DV)

Vitamin

B6: 0.21 mg (12.4% DV)

Niacin:

1.9 mg (11.9% DV)

Good source of:

Magnesium:

41 mg (9.8% DV)

Phosphorus:

69 mg (5.5% DV)

Iron:

0.93 mg (5.2% DV)

Also provides:

Thiamin:

0.05 mg (4.2% DV)

Vitamin

A: 39 mcg (4.3% DV)

Zinc:

0.44 mg (4% DV)

Calcium:

43 mg (3.3% DV)

Vitamin

E: 0.43 mg (2.9% DV)

Folate:

4 mcg (1% DV)

Provides trace amounts:

Vitamin

C: 0.6 mg (0.67% DV)

Nutrient Profile:

Fresh Plum20

Macronutrient Profile: (Per 100g fresh

plum; approximately 2/3 cup sliced plums)

46 calories

0.7 g

protein

11.4

g carbohydrate

0.3 g

fat

Secondary Metabolites: (Per 100 g fresh

plum; approximately 2/3 cup sliced plums)

Very good source of:

Vitamin

C: 9.5 mg (10.6% DV)

Good source of:

Vitamin

K: 6.4 mcg (5.3% DV)

Also provides:

Dietary

Fiber: 1.4 g (4.7% DV)

Potassium:

157 mg (3.3% DV)

Niacin:

0.42 mg (2.6% DV)

Thiamin:

0.03 mg (2.3% DV)

Riboflavin:

0.03 mg (2% DV)

Magnesium:

7 mg (1.7% DV)

Vitamin

B6: 0.03 mg (1.7% DV)

Folate:

5 mcg (1.3% DV)

Phosphorus:

16 mg (1.3% DV)

Provides trace amounts:

Iron:

0.17 mg (0.9% DV)

Calcium:

6 mg (0.5% DV)

DV =

Daily Value as established by the US Food and Drug Administration, based on a

2,000-calorie diet.

|

Recipe: Spiced Plum Crumble with Pistachios

Courtesy of Bon Appétit21

Ingredients:

- 3 pounds

ripe plums, pitted and sliced 1/3" thick (about 8 cups)

- 2 teaspoons

finely grated lemon zest

- 2 tablespoons

fresh lemon juice

- 1/4

cup cornstarch

- 1/2

cup plus 1/3 cup packed light brown sugar

- 1 teaspoon

kosher salt, divided

- 3/4

teaspoon ground cardamom or ground

cinnamon, divided

- 3/4

cup all-purpose flour

- 6 tablespoons

chilled unsalted butter, cut into small pieces

- 2

tablespoons coarsely chopped raw pistachios

Preparation:

- Place

a rack in lower third of oven and heat to 350°F.

- Toss

plums, lemon zest, lemon juice, cornstarch, 1/2 cup brown sugar, 1/2 teaspoon

salt, and 1/4 teaspoon cardamom or cinnamon in a large bowl. Let sit 5–10

minutes, until some juices accumulate.

- Meanwhile,

pulse flour and remaining 1/3 cup brown sugar, 1/2 teaspoon salt, and 1/2 teaspoon

cardamom or cinnamon in a food processor to combine. Add butter and pulse

until mixture is sandy in texture and starts to form larger clumps.

- Transfer

plum mixture to a 9”-diameter deep pie dish or an 8” x 8” baking dish.

- Scatter

topping over fruit, squeezing small fistfuls together before breaking into

smaller pieces of varying sizes. Sprinkle pistachios evenly over topping.

- Bake

crumble for 40-45 minutes until juices are thickened and bubbling and top is

golden brown. Let cool 5-10 minutes before serving.

|

Image credits (top to bottom):

Prunus domestica. ©2019

Steven Foster.

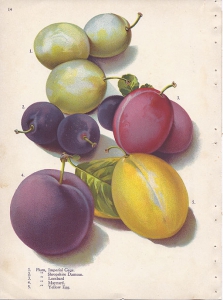

Illustration of P. domestica varieties by Alois Lunzer from Brown Brothers Continental Nurseries Catalog. 1909.

P. domestica. Image courtesy of Flagstaffotos.

P. domestica. ©2019

Steven Foster.

References

- Plum.

New World Encyclopedia website. Available at: www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Plum.

Accessed on September 24, 2019.

- Plum.

Encyclopedia Britannica website. Available at: www.britannica.com/plant/plum.

Accessed on September 24, 2019.

- National Geographic Society. Edible: An Illustrated Guide to the World’s Food Plants. Lane Cove,

Australia: Global Book Publishing; 2008.

- Van Wyk B-E. Food Plants of the World.

Portland, OR: Timber Press; 2006.

- Plum.

Leafnetworkaz website. 2019. Available at:

https://leafnetworkaz.org/resources/PLANT%20PROFILES/Plum_profile.pdf Accessed September

24, 2019.

- Murray M. The

Encyclopedia of Healing Foods. New York, NY: Atria Books; 2005.

- Igwe

E, Charlton K. A systematic review on the health effects of plums (Prunus domestica and Prunus salicina). Phytotherapy Research. 2016;30:701-731.

- Wallace

T. Dried plums, prunes and bone health: a comprehensive review. Nutrients. 2017;9(401):1-21.

- Plums.

Agricultural Marketing Resource Center. Available at: www.agmrc.org/commodities-products/fruits/plums.

Accessed November 9, 2019.

- Stacewicz-Sapuntzakis

M. Dried plums and their products: composition and health effects – an updated

review. Critical Reviews in Food Science

and Nutrition. 2012;53(12):1277-1302.

- Arjmandi

B, Khalil D, Lucas E, et al. Dried plums improve indices of bone formation in

postmenopausal women. Journal of Women’s

Health & Gender-Based Medicine. 2002;11(1):1-10.

- Lever

E, Scott SM, Louis P, et al. The effects of prunes on stool output, gut transit

time and gastrointestinal microbiota: A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Nutrition. 2019;38:165-173.

- Hooshmand

S, Chai S, Saadat R, et al. Comparative effects of dried plum and dried apple

on bone in postmenopausal women. British

Journal of Nutrition. 2011;106:923-930.

- Lever

E, Cole J, Scott SM, et al. Systematic review: The effect of prunes on

gastrointestinal function. Alimentary

Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 2014;40:750-758.

- Hooshmand

S, Kern M, Metti D, et al. The effect of two doses of dried plum on bone

density and bone biomarkers in osteopenic postmenopausal women: A randomized

controlled trial. Osteoporosis

International. 2016;27:2271-2279.

- Arjmandi

B, Johnson S, Pourafshar S, et al. Bone-protective effects of dried plum in

postmenopausal women: Efficacy and possible mechanisms. Nutrients. 2017;9(495):1-20.

- Schreurs

A, Shirazi-Fard Y, Shahnazari M, et al. Dried plum diet protects from bone loss

caused by ionizing radiation. Scientific

Reports. 2016;6(21343):1-12.

- Simonavice

E, Liu PY, Ilich J, Kim JS, Arjmandi B. The effects of 6-month resistance

training and dried plum consumption, blood markers of bone turnover, and

inflammation in breast cancer survivors. Applied

Physiology and Nutrition. 2014;39:730-739.

- Plums,

dried (prunes), uncooked. USDA Food Data Central. Available at: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/168162/nutrients.

Accessed November 12, 2019.

- Plum,

raw. USDA Food Data Central. Available at: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/341614/nutrients.

Accessed November 12, 2019.

- Baz

M. Plum-Cardamom Crumble with Pistachios. Bon

Appétit. August 2018. Available at: www.bonappetit.com/recipe/plum-cardamom-crumble-with-pistachios

Accessed on November 11, 2019.

|