By Connor Yearsley

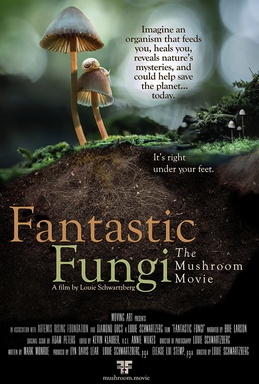

Fungi

frequently are forgotten and taken for granted. In fact, without knowing it,

people trod over about 300 miles of sprawling fungi with each step. That is

according to Fantastic Fungi: The Magic

Beneath Us, a documentary film that was released in the United States in

October 2019. The film currently holds a 100% rating on review aggregate

websites Rotten Tomatoes and Flixster. Fungi

frequently are forgotten and taken for granted. In fact, without knowing it,

people trod over about 300 miles of sprawling fungi with each step. That is

according to Fantastic Fungi: The Magic

Beneath Us, a documentary film that was released in the United States in

October 2019. The film currently holds a 100% rating on review aggregate

websites Rotten Tomatoes and Flixster.

Directed

by Louie Schwartzberg, written by Mark Monroe, and narrated by Brie Larson, the

film features interviews with a host of notable naturalists and scientists,

including Andrew Weil, MD, and Dennis McKenna, PhD. Renowned mycologist (fungi

expert) Paul Stamets, however, is definitely the star. Throughout, his

enthusiasm and passion for fungi are contagious, and the insights he shares reflect

a lifetime of research and knowledge.

The

film is replete with stunning visuals and cinematography that may be worth the

watch alone. This includes fascinating time lapses of fungi growing and

breaking down everything from fruit to termites to a mouse. Kaleidoscopic

geometric patterns occur throughout and presumably are meant to elicit the

feeling of using the psychedelic compound psilocybin (derived primarily from

the fungal genus Psilocybe [Hymenogastraceae]). In key places, the music by Adam

Peters elevates and reinforces the mood.

In the

film, Stamets says that fungi “can heal you. They can feed you. They can kill

you.” Though the focus is mostly on the positive aspects of fungi and

mycophilia, or the love of fungi, it is admitted that mycophobia, or a fear of

fungi, exists too, perhaps because of their association with death, decay, and disease.

The film emphasizes that while fungi do represent the end of life, they also

represent the beginning of life and enable restoration, rejuvenation, and

resurrection. Described as nature’s “digestive tract,” fungi help generate

life-giving soils.

A

recurring theme is how fungi are omnipresent on one hand but “hidden” from view

on the other. In fact, humans inhale fungal spores with each breath, from their

first breath to their last. Fungi are out of sight, out of mind, and typically much

less conspicuous than members of the plant and animal kingdoms. The

interconnectedness of fungi, plants, and animals is also explored. For

instance, nutrients can pass from tree to tree through underground fungal

“passageways,” and, after trees remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, much

of that carbon travels underground, where it is stored by fungi. Without fungi,

plant life would choke the Earth, the film explains.

The

incredible diversity of fungi is also a central topic, from luminescent and

purple fungi to the Earth’s largest (by area) known living organism: a specimen

of Armillaria ostoyae (Physalacriaceae) called the “Humongous Fungus” in

Oregon. “Pando,” a clonal colony of quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides, Salicaceae) trees in Utah, however, is considered

the largest known living organism by mass. The

incredible diversity of fungi is also a central topic, from luminescent and

purple fungi to the Earth’s largest (by area) known living organism: a specimen

of Armillaria ostoyae (Physalacriaceae) called the “Humongous Fungus” in

Oregon. “Pando,” a clonal colony of quaking aspen (Populus tremuloides, Salicaceae) trees in Utah, however, is considered

the largest known living organism by mass.

Fungi,

which produce chemical compounds that are not produced by other organisms, are

proposed as sources of viable solutions to many of the world’s biggest problems,

from human to environmental health concerns. Stamets stresses the importance of

preserving old-growth forests as repositories of fungal resources. As

explained, fungi can break down oil and filter water. And lion’s mane (Hericium erinaceus, Hericiaceae) may be able to promote the regeneration

of nerve cells, which suggests possible benefits for people with Alzheimer’s

disease, for example. These and a wealth of other abilities led some people in

the film to describe feeling empowered by fungi.

The use

of fungi to reduce viruses in honeybees, which was covered extensively in HerbalGram issue 125,1 is

mentioned briefly, but I would have liked a longer segment on this important

and timely research. This could have been an opportunity for some great

videography showing the bees and fungi in action. The film also could have

discussed the potential importance of a fungus’ substrate (the material on or

from which an organism lives, grows, and/or obtains its nourishment), and how

it can impact the fungus’ chemistry and value.

Much of

the second half is dedicated to psilocybin. As explained, psilocybin can induce

synesthesia, or a blending of the senses (e.g., hearing colors). The film

suggests that psilocybin use by ancestors of modern humans may have played a

role in the development of the modern human brain. The recent history of

psilocybin is covered, from its introduction into popular culture by the

ethnomycologist Robert Gordon Wasson (1898-1986), to its stigmatization and,

recently, the resurgence of interest in its therapeutic use.

The

testimonies of two end-stage cancer patients, a man and a woman, are

particularly meaningful. They participated in recent clinical trials that

assessed the effects of psilocybin on depression and anxiety associated with existential

distress.2 The man  said that just a single dose of psilocybin made

him more comfortable with living because he was no longer afraid of dying.

Despite the stigma against psilocybin, given its hallucinatory effects, after

hearing these testimonies, it is difficult to deny that it can have profound,

life-changing effects for some people in some circumstances, whether extenuating

or not. In fact, the film explains that many study participants ranked their

psilocybin session among the most meaningful experiences of their lives, and

many compared it to the birth of their first-born child. said that just a single dose of psilocybin made

him more comfortable with living because he was no longer afraid of dying.

Despite the stigma against psilocybin, given its hallucinatory effects, after

hearing these testimonies, it is difficult to deny that it can have profound,

life-changing effects for some people in some circumstances, whether extenuating

or not. In fact, the film explains that many study participants ranked their

psilocybin session among the most meaningful experiences of their lives, and

many compared it to the birth of their first-born child.

As this review may just scratch the surface

of the film, the film itself may just scratch the surface of the fungi kingdom,

which is described as a “frontier of knowledge.” This is not a criticism, at

all, but more a testament to the subject. In fact, perhaps it speaks to how

much people take fungi for granted and how little is known about them that they

could be summarized so well in Fantastic Fungi, which runs only 81

minutes. To summarize plants, for example, in one documentary of equal length

would seem impossible, even though fungal species greatly outnumber plant

species and have existed longer than land plants.3 After watching Fantastic

Fungi, maybe more people will become mycophiles; be left with a greater

appreciation of the complexity, diversity, and versatility of these organisms;

and be inspired to expand the knowledge-base and find the next fungal-related

scientific breakthrough.

Schwartzberg

said he loves taking audiences on journeys through time and scale (oral

communication, March 12, 2020). “I really try to share the wonders of nature’s

intelligence, by making the invisible visible and using cinematic techniques

like time lapse, slo-mo, micro, and macro,” he said. “By showing nature’s beauty,

rhythm, and patterns, I want people to fall in love with nature, because if

people fall in love with it, then they will protect it. We need that to create

a sustainable future for our planet.

“One

thing that I discovered [while] making Fantastic

Fungi is that the underground mycelial network is a beautiful economy where

nutrients are shared for ecosystems to flourish,” Schwartzberg added. “I hope

audiences will take away [the idea] that communities survive better than

individuals. Nothing in nature lives alone. This could be a model for us to

replicate in our cultural and political society. Sharing is nature’s way of

doing things.” “One

thing that I discovered [while] making Fantastic

Fungi is that the underground mycelial network is a beautiful economy where

nutrients are shared for ecosystems to flourish,” Schwartzberg added. “I hope

audiences will take away [the idea] that communities survive better than

individuals. Nothing in nature lives alone. This could be a model for us to

replicate in our cultural and political society. Sharing is nature’s way of

doing things.”

The

film presented challenges. “Shooting time lapse is a very slow and difficult

process filled with a lot of failure,” Schwartzberg said. “It takes a

tremendous amount of patience. I have had cameras running non-stop for decades

in my studio. And all of that time is squeezed into hours of film. So, it is very

challenging, but the results are breathtaking.”

Stamets is “very pleased” with the film and

would consider making another with Schwartzberg (email,

March 5, 2020).

“Louie approached me after seeing my lecture at a

Bioneers conference in the mid-1990s,” Stamets wrote. “He showed me some time

lapses that blew my mind. After I [later] committed, it took [more than a

decade]! I wanted to show how we are all interconnected via

mycelia [the vegetative part of a fungus’ life cycle that consists of many

threadlike tubes], and

that mycelia have the resources to help us and our ecosystems

survive and improve. We share a great consciousness with nature, and mushrooms

are a portal. We need to reconnect with each other and with nature. That most

showings of the film were sold out reflects the hunger that has built up for

the need to understand the meaning of our being.”

The

film is available on www.fantasticfungi.com for digital download

($14.99) and streaming ($4.99). Image credits All images courtesy of Moving Art. Top to bottom:

Movie poster

Blue oyster fungus (Pleurotus ostreatus, Pleurotaceae). Credit: Upthink

Mycena chlorophos (Mycenaceae). Credit: Steve Axford

Pink oyster fungus (P. salmoneo-stramineus). Credit: Upthink

References

- Yearsley C. Can

Fungi Ease Disease in Bees? HerbalGram.

2020;125:66-73. Available at: http://cms.herbalgram.org/herbalgram/issue125/hg125-feat-bee.html. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- Yearsley C.

Psilocybin Reduces Symptoms of Anxiety and Depression in Patients with Cancer

in Two Clinical Trials. HerbalGram. 2017;114:38-42.

Available at: http://cms.herbalgram.org/herbalgram/issue114/hg114-resrvw-psilocy.html. Accessed March 30, 2020.

- Heckman DS, Geiser DM, Eidell BR, Stauffer

RL, Kardos NL, Hedges SB. Molecular evidence for the early colonization of land

by fungi and plants. Science. 2001;293(5532):1129-1133. doi: 10.1126/science.1061457.

|