Editor’s note: Every other

month, HerbalEGram highlights a conventional food and briefly explores its

history, traditional uses, nutritional profile, and modern medical research. We

also feature a nutritious recipe for an easy-to-prepare dish with each article

to encourage readers to experience the extensive benefits of these whole foods.

With this series, we hope our readers will gain a new appreciation for the foods

they see at the supermarket and frequently include in their diets. We would like to

acknowledge ABC Chief Science Officer Stefan Gafner, PhD, and HerbalGram Associate Editor Hannah Bauman for their contributions to

this project.

By Jenny Perez, ABC Education Coordinator

Overview

The cashew (Anacardium occidentale) belongs to the

sumac family (Anacardiaceae), a tropical and subtropical plant family known for

caustic resins that can cause allergic reactions. Members of this plant family,

including poison ivy (Toxicodendron

radicans) and poison sumac (T.

vernix), have resin ducts in the bark which exude gums and resins that

become black when exposed to air.1 In addition to the cashew plant, other

economically important fruits and nuts in the sumac family include mango (Mangifera indica), sumac berry (Rhus spp.) and pistachio (Pistacia

vera).1

The cashew is an

evergreen tree with an irregularly shaped trunk and twisted, crooked branches that can grow to a height of 40 feet.2-4 Cashew trees can thrive in the tropical

climates of Central and South America, where soils are thin and humidity is

high.2,3 Its leathery leaves have smooth margins and are two to

eight inches long, up to six inches wide, elliptical in shape, and spirally

arranged around the stem.2,3 The tree produces 10-inch long panicles

(multi-branched infloresences) of seven-petaled, small fragrant flowers that

change from pale green to a coppery-pink color after pollination has occured.3,4

The true fruit of the tree is the one-inch-long, kidney-shaped, nut-like fruit,

commercially known as the cashew nut.3,5

can grow to a height of 40 feet.2-4 Cashew trees can thrive in the tropical

climates of Central and South America, where soils are thin and humidity is

high.2,3 Its leathery leaves have smooth margins and are two to

eight inches long, up to six inches wide, elliptical in shape, and spirally

arranged around the stem.2,3 The tree produces 10-inch long panicles

(multi-branched infloresences) of seven-petaled, small fragrant flowers that

change from pale green to a coppery-pink color after pollination has occured.3,4

The true fruit of the tree is the one-inch-long, kidney-shaped, nut-like fruit,

commercially known as the cashew nut.3,5

The cashew “apple,”

which more closely resembles a pear (Pyrus spp., Rosaceae) in shape, is

an accessory fruit, or false fruit (pseudofruit), that develops from the

receptacle of the flower rather than the flower itself.3,4 It is reddish

or yellow in color and grows up to four inches — three times the size of the cashew

nut, or true fruit. 2,3 The true fruit of the cashew tree is a drupe

that grows at the end of the pseudofruit and consists of two walls or shells. The

outer shell is smooth, thin, and elastic, and changes in color from olive green

to pale brown when ripe.2,3 Within the drupe is a single seed: the

cashew nut.3 The seed is surrounded by a double shell containing a

mixture of anacardic acids, which are closely related to urushiol (the caustic oily

mixture exuded by poison ivy).3

Historical and Commercial Uses

The cashew tree is

called maranon in most

Spanish-speaking countries, but known as merey

in Venezuela.5 In northeastern Brazil, the cashew tree is regionally

known as cajueiro and the fruit is

called caju, which is derived from what indigenous

peoples called acaju or acajous (“to pucker the mouth”), referring to the astringent flavor

of the fruit.3,4 During the late 16th century, Portuguese traders

brought the cashew plant to eastern Africa and India, where it thrived in nutrient-deficient

sandy soils and was used as a fast-growing soil retainer near the seacoast.2,4,5

Once naturalized, cashew trees were extremely hardy and drought tolerant,

living 30 to 40 years in the extreme tropical heat of these regions.4-6

When the low-growing, gnarled branches of the cashew tree rest upon the ground,

they take root and can form extensive forests in the tropical lowlands of

northern South America, Central America and the West Indies.4,5

Cashe w trees are

economically important, and their components have numerous uses. The wood from

cashew trees can be used for shipping crates, boats, and charcoal.5

The rough bark contains resin, acrid sap, and a gum similar to gum arabic (Senegalia senegal, Fabaceae).4,5

Untreated wood from the cashew tree may cause allergic reactions and must be

handled with care by susceptible individuals.2 Resins from the unprocessed

cashew seed are commercially known as cashew nut seed liquid (CNSL) and are considered

an important agricultural byproduct of cashew production.3 CNSL is used

as an insecticide, wood varnish, industrial sealant, laminating resin, epoxy

resin, rubber compounding resin, and in cashew cement and other industrial

applications.2,3 The caustic, acrid-tasting resin present between

the inner and outer cashew shell is used topically as a traditional medicine to

remove corns and warts.5 w trees are

economically important, and their components have numerous uses. The wood from

cashew trees can be used for shipping crates, boats, and charcoal.5

The rough bark contains resin, acrid sap, and a gum similar to gum arabic (Senegalia senegal, Fabaceae).4,5

Untreated wood from the cashew tree may cause allergic reactions and must be

handled with care by susceptible individuals.2 Resins from the unprocessed

cashew seed are commercially known as cashew nut seed liquid (CNSL) and are considered

an important agricultural byproduct of cashew production.3 CNSL is used

as an insecticide, wood varnish, industrial sealant, laminating resin, epoxy

resin, rubber compounding resin, and in cashew cement and other industrial

applications.2,3 The caustic, acrid-tasting resin present between

the inner and outer cashew shell is used topically as a traditional medicine to

remove corns and warts.5

In the international

tree nut trade, cashew ranks third in global sales, with more than 20% of the

market, and it is considered the second-most-expensive nut traded in the United

Sates, after macadamia (Macadamia spp., Proteaceae) nuts.6,7 Cashew

processing and exportation began in the 1950s in India, and consumer demand has

steadily increased.6 Cashews are produced in 32 countries with

tropical and subtropical climates. According to published Food and Agriculture

Organization (FAO) data, in 2005, the three major cashew-producing countries were

India, Brazil, and Indonesia, followed by Vietnam and Nigeria.2,3,5 Global

annual production was reported to be 2.7 million tons.3

Cashew nut kernels

are not true nuts and must be carefully processed before consuming. Processing

involves several labor-intensive steps and must be undertaken with care due to the

brown, oily resin composed mainly of anacardic acids in the nut shell that can

blister human skin.2,6 First, the nuts are removed from the cashew

apple and then baked to loosen the inner and outer shells. This process often

takes place in a roasting cylinder to avoid exposure to and inhalation of the

caustic fumes caused by the burning resin. The shells are then removed by hand to

harvest the edible seed inside.2,3,7 Processing cashew nuts is

somewhat hazardous, and workers must wear gloves to avoid painful skin rashes.3,6

The thin,

reddish-brown seed coat of the cashew, which contains 25% tannins, is difficult

to remove, causes astringent, tingling sensations in the mouth, and generally is

not desired by consumers.6,7 Cashews that are whole, white, and without

a seed coat (sold as “raw”) are considered high quality.6 Unfortunately,

the removal of the seed coat also removes potent antioxidants, catechin and

epicatechin, which are only present in the seed coat.7 More recent

cashew-processing techniques enable the removal of the caustic CNSL while leaving

the cashew skins intact, which increases levels of phenolic compounds compared

to skinless cashew products.6

Cashew nuts are rich

in oils and versatile in use, providing a distinct flavor in numerous chicken

and vegetarian dishes of southern India and Asia. In Chinese cooking, cashews

are often added to stir fries.4 In Western countries, cashews are

consumed as a protein-rich snack food.2 Cashew nuts can be easily

ground into a spread similar to peanut (Arachis hypogaea, Fabaceae) butter.2,4

The fragile cashew

apple must be hand-picked and the curved fruits detached before being

sun-dried.2 Due to the hazards of processing the cashew nut, Latin

Americans and West Indians commonly discard the nut and enjoy the juicy cashew

apple instead. Cashew apples are highly perishable due to their susceptibility

to various yeast and fungi post-harvest.3,5 The juicy, acidic pulp of

cashew apples is consumed fresh or used in beverages, jellies, and chutneys.2

Cashew apple juice is very astringent and contains over 30% tannins.5

In Cuba and Brazil, cashew apple juice was prescribed as a remedy for sore

throats and chronic dysentery.5 to the hazards of processing the cashew nut, Latin

Americans and West Indians commonly discard the nut and enjoy the juicy cashew

apple instead. Cashew apples are highly perishable due to their susceptibility

to various yeast and fungi post-harvest.3,5 The juicy, acidic pulp of

cashew apples is consumed fresh or used in beverages, jellies, and chutneys.2

Cashew apple juice is very astringent and contains over 30% tannins.5

In Cuba and Brazil, cashew apple juice was prescribed as a remedy for sore

throats and chronic dysentery.5

In Brazil, the pulp

is fermented to make a vinegar called anacard,

the juice is consumed diluted and sweetened as a refreshing beverage known as cajuina, distilled into liquor, or

fermented into a Madeira-like wine known as cajuada.3,4

Similarly, in Goa, India, the juicy pulp of the cashew apple is used to prepare

fenny, a regionally popular distilled liquor. In Nicaragua, cashew apples are

consumed fresh, made into juice, and used to create sweets, jellies, wine, and

vinegar.5 Despite the versatility of the cashew apple, in many parts

of the world, the cashew apple is discarded after the nut is removed because of

its short shelf life.3

Nutrients and Phytochemicals

Nuts can help manage

blood cholesterol levels, which is an important component of cardiovascular

health.8 Cashew nut kernels are nutrient and calorie dense. They

contain protein, cholesterol, more carbohydrates than other nuts (with the

exception of pistachios), and are high in fat, most of which is unsaturated.4

Its high energy and protein content are ideal for growing children, pregnant

and nursing mothers, and those recovering from illness.7

Cashews, along with almonds

(Prunus dulcis, Rosaceae) and pistachios, have the highest protein of

all tree nuts.6 The predominant amino acid is arginine, which plays

a role in the vasodilation of blood vessels.6 Despite cashew nut’s

high protein content, its biological value (BV), or protein bioavailability, is

low due to the limited content of essential amino acids, especially lysine.6

Since essential amino acids represent the bottleneck in protein production in

the human body, protein sources with low quantities of essential amino acids

have a lower BV.

The most abundant

vitamin in cashew nuts is vitamin E (α- and γ-tocopherols), which protects unsaturated

fatty acids from becoming damaged through oxidation.6,8 Cashews

contain one of the highest levels of vitamin K of all nuts, an important

vitamin for bone health and immunity.6 Like most nuts, cashews are rich

in minerals, including potassium, magnesium, and calcium, all of which are important

for maintaining bone health, heart health, and many other important body

functions.7 Levels of phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium are high

enough to substantiate US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved nutrition

label claims.6 Cashew nuts also contain copper, iron, and zinc.7 The most abundant

vitamin in cashew nuts is vitamin E (α- and γ-tocopherols), which protects unsaturated

fatty acids from becoming damaged through oxidation.6,8 Cashews

contain one of the highest levels of vitamin K of all nuts, an important

vitamin for bone health and immunity.6 Like most nuts, cashews are rich

in minerals, including potassium, magnesium, and calcium, all of which are important

for maintaining bone health, heart health, and many other important body

functions.7 Levels of phosphorus, potassium, and magnesium are high

enough to substantiate US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved nutrition

label claims.6 Cashew nuts also contain copper, iron, and zinc.7

Foods containing high

levels of monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) and polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs)

are associated with a lower risk of cardiovascular disease (CVD).6,9

There is growing evidence that replacing refined grains with healthy fats, such

as MUFAs, may improve high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol levels.10

This is important since just a 1% increase in HDL cholesterol levels is

associated with a 3% reduction in CVD risk. However, cashew nuts also contain 20%

saturated fat and deliver four grams of saturated fat per 50-gram serving.9

This excludes cashews from being officially listed by the FDA as a food

associated with reducing risk of CVD.

Recent studies suggest

that stearic acid, one of the most abundant saturated fats in cashews, has a

neutral effect when used to replace carbohydrates or cholesterol-raising saturated

fatty acids (SFAs), despite the widespread misconception that all high-calorie,

high-fat snacks result in increased cholesterol levels and, potentially, weight

gain.11 Additionally, cashew nuts also contain other heart-healthy

components such as glutamic acid, arginine, cholesterol-lowering phytosterols, and

a variety of phenolic compounds (Table 1).6,8 Cashews also contain

significant levels of phosphatidylcholine, a phospholipid that improves cell

membrane integrity and precursor to acetylcholine, the main neurotransmitter involved

with muscle movements, memory, and circadian rhythms.7

Table 1. Primary Bioactive

Compounds Present in Cashew Nut6-8

|

Phytochemical

|

Compound Type

|

Plant Part

|

Associated Properties

|

|

Lutein

|

Carotenoid

|

Nut

|

Protects mucus

membranes and macula of eye from oxidation and UV damage

|

|

Zeaxanthin

|

Carotenoid

|

Nut

|

Protects mucus

membranes and macula of eye from oxidation and UV damage

|

|

Βeta-sitosterol

|

Phytosterol

|

Nut

|

Lowers cholesterol

absorption

|

|

Catechin

|

Flavanol

|

Nut seed coat

|

Building block of

proanthocyanidins; potent antioxidant

|

|

Epicatechin

|

Flavanol

|

Nut seed coat

|

Building block of

proanthocyanidins; potent antioxidant

|

|

Tannins

|

Polyphenol

|

Nut seed coat

|

Astringent,

anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial

|

Modern Research and Potential Health Benefits

The dietary role of

nuts is considered vital to human nutrition. Nut-producing trees are perennial

edible crops and reliably yield significant amounts of nutrient- and energy-dense

nuts for decades once the tree matures. Similar to other tree nuts, cashew

kernels have been studied primarily for their cardiovascular and metabolic

health benefits.

Cardiovascular Effects

CVD is the leading

cause of death globally, accounting for more than four million deaths annually

in Europe and nearly 930,000 deaths annually in the United States.11

In epidemiological studies, the consumption of tree nuts in the diet is

associated with a reduced risk of CVD. While not a true tree nut, the cashew nut

has similar characteristics nutritionally and phytochemically that validate its

benefits as a nutrient-dense part of healthy diets.

In a randomized,

crossover, isocaloric, controlled-feeding study, 51 men and women with median low-density

lipoprotein (LDL) concentrations of 159 mg/dL at screening participated in two

28-day intervention periods with a two-week washout period between

interventions.9 During each intervention, participants consumed

either 28-64 grams daily of roasted salted cashews or baked potato (Solanum

tuberosum, Solanaceae) chips, both providing 11% of daily total calories.

Otherwise, participant diets were designed to reflect that of a typical US

adult (49% carbohydrates, 16% protein, 33% fat). MUFA intake increased in the

cashew group without affecting SFAs and PUFAs. Study results indicate that the cashew

group had significantly decreased LDL cholesterol and total cholesterol levels

compared with the potato chip group and no significant changes in triglyceride

or HDL cholesterol levels. However, the cashew group also reported more adverse

events. Of the 14 adverse events reported, eight were classified as possibly or

probably related to consuming cashews and included constipation, bloating,

increase in pain from pre-existing inflammatory conditions like arthritis and

gout, weight gain, fatigue, and general malaise.

Some clinical trials

indicate that cashew supplementation may have further drawbacks. In a similar

randomized crossover trial, 42 individuals participated in a controlled-feeding

study with two treatment phases.11 The same diet was provided in

both phases with no additions during the control phase and a 42-gram daily

addition of cashews during the cashew nut phase. Diet and calorie intake were

adjusted to achieve similar caloric intake of overall diets in both phases.

After four weeks, CVD risk factors were measured, but there were no significant

differences in blood lipids, blood pressure, augmentation index (an indicator

of arterial stiffness), blood glucose, endothelin, adhesion molecules, or

clotting factors. In fact, participants consuming the baseline diet with the

addition of cashews experienced a significant increase in tumor necrosis factor-α

(TNF-α) levels compared to those only consuming baseline diet, which indicates

that cashew consumption may be associated with increased inflammation in the

body. Cashew consumption was also associated with a decreased concentration of proprotein

convertase subtilisin/kexin type 9 (PCSK9), which is associated with improved

removal of LDL cholesterol from the bloodstream.

Metabolic Effects

Evidence suggests

that consuming 60 grams of nuts daily may reduce fasting blood glucose and

glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).10 These attributes are crucial

to diabetes management and cardiovascular health. A recent meta-analysis of

clinical trials indicates that despite the high calorie and fat content of nuts,

long-term nut consumption is not associated with significant effects on body

weight when included in a healthy diet, and is in fact associated with a lower

risk of obesity.7,10 Possible mechanisms that may explain this

outcome include the thermogenic effects of readily oxidizable MUFAs and PUFAs,

incomplete nut mastication resulting in lost calories via stool elimination,

and enhanced satiety that results in less-frequent snacking.10 Evidence suggests

that consuming 60 grams of nuts daily may reduce fasting blood glucose and

glycosylated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c).10 These attributes are crucial

to diabetes management and cardiovascular health. A recent meta-analysis of

clinical trials indicates that despite the high calorie and fat content of nuts,

long-term nut consumption is not associated with significant effects on body

weight when included in a healthy diet, and is in fact associated with a lower

risk of obesity.7,10 Possible mechanisms that may explain this

outcome include the thermogenic effects of readily oxidizable MUFAs and PUFAs,

incomplete nut mastication resulting in lost calories via stool elimination,

and enhanced satiety that results in less-frequent snacking.10

In a parallel-arm,

RCT study, adults with type 2 diabetes with low HDL as well as dyslipidemia

consumed their normal diet with or without 30 grams of raw cashews daily for 12

weeks.10 Those consuming the cashew nuts did so mid-morning or as an

evening snack, not as a cooking ingredient. No other type of nut was consumed.

Participants met with dietitians six times during the 12-week period to

complete diet recalls, including a single 24-hour recall at baseline for

participants in both groups. At the end of the study, those in the cashew group

had a significant reduction in systolic blood pressure compared to the those in

the control group. HDL levels were significantly improved from baseline, but there

were no significant reductions in LDL cholesterol or other blood lipid markers.10,11

Despite the significant increase in daily caloric intake by those in the cashew

group, participants did not experience an increase in weight, body mass index

(BMI), or waist circumference.

Consumer Considerations

Globally, cashews are

one of the most popular tree nuts7 and have clinically supported

cardiovascular benefits when added to typical American diet.9 Cashew

oil can be extracted from the seed and used for culinary purposes.3 Although

less frequent than tree nut allergies, cashews can cause allergic reactions in

some individuals.3

Epidemiological

evidence indicates that more than 170 foods can cause immunoglobulin E (IgE)-mediated

allergic reactions.8 Cashew proteins are associated with potent

allergic reactions. Anacardein is the main soluble protein in cashews (accounting

for 40-45% of the total soluble proteins in cashew nuts) and is believed to be

the main trigger for hypersensitivity reactions when consumed.7 Cashew

nuts can cause two distinct hypersensitivity reactions: contact dermatitis

(linked to cardol and anacardic acid present in CNSL) and IgE-mediated food

allergy. Reactions can range from atopic dermatitis to fatal systemic allergic

reactions.7 Approximately 20% of patients with type 1

hypersensitivity to cashew nut experience anaphylaxis.7 Reports

reveal that cashew nut allergy is most common in young children (< four

years old) and adult females.8

Consumers should be

aware that cashew nut powder is often added to chocolate (from Theobroma

cacao, Malvaceae) and milk-based products.7 Recent research

indicates that the powdered milk used in manufacturing milk chocolate powder

can contain approximately 25% roasted cashew kernel.8 Moreover,

cashew processing treatments such as autoclaving, blanching, frying, and

microwave heating have no effect on cashew nut allergens.8

Nutrient Profile12

Macronutrient Profile: (Per one ounce raw cashews)

157 calories

5 g protein

9 g carbohydrate

12 g fat

Micronutrient

Profile: (Per one ounce raw cashews)

Excellent source of:

Copper: 0.62 mg (41%

DV)

Zinc: 1.64 mg (20.5%

DV women; 15% DV men)

Manganese: 0.47 mg (20.4%

DV)

Very good source of:

Magnesium: 82.8 mg (19.7%

DV)

Phosphorus: 168 mg (13.4%

DV)

Iron: 1.89 mg (10.5% DV)

Selenium: 5.64 mcg

(10.3% DV)

Good source of:

Vitamin K: 9.67 mcg (8%

DV)

Vitamin B6:

0.12 mg (7% DV)

Also provides:

Potassium: 187 mg (4%

DV)

Dietary Fiber: 0.94 g

(3% DV)

Niacin: 0.30 mg (2%

DV)

Folate: 7.1 mcg (1.8%

DV)

Vitamin E: 0.25 mg (1.7%

DV)

Riboflavin: 0.02 mg

(1.5% DV)

Trace amounts:

Calcium: 10.5 mg

(0.8% DV)

Vitamin C: 0.14 mg (0.2%

DV)

Thiamin: 0.12 mg (0.1%

DV)

DV = Daily Value as

established by the US Food and Drug Administration, based on a 2,000-calorie

diet.

|

Recipe: Stir-Fried

Vegetables with Toasted Cashews

Courtesy of Food

and Wine13

Ingredients:

- 3 tablespoons vegetable or chicken broth

- 1 teaspoon cornstarch

- 3 tablespoons cooking oil

- 2/3 cup cashews

- 1 pound mushrooms, sliced thin

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 4 scallions, white bulbs sliced thin, green tops

chopped and reserved separately

- 3/4 teaspoon toasted sesame oil

- 3 cloves garlic, minced

- 1 quart broccoli florets (for more information on

the benefits of broccoli, click here14)

- 1 ½ quarts napa cabbage, shredded

- 1/4 teaspoon dried red pepper flakes

- 1 tablespoon oyster sauce

- 2 tablespoons soy sauce or tamari

Directions:

- In a small bowl, combine 1 tablespoon of broth with

the cornstarch and stir to make a slurry.

- In a wok or a large nonstick frying pan, heat 1/2

tablespoon of cooking oil over medium-high heat. Add cashews and cook until

starting to brown, 1-2 minutes. Transfer the nuts to a medium bowl.

- In the same pan, heat 1 tablespoon cooking oil over

medium-high heat. Add the mushrooms and 1/4 teaspoon salt and cook, stirring

occasionally, until golden brown, about five minutes. Transfer to the bowl

with the cashews.

- Add the scallion greens and sesame oil into the

bowl with mushrooms and cashews and stir to combine.

- Heat the remaining 1 ½ tablespoons cooking oil over

medium-high heat. Add the scallion whites and garlic and cook for 30 seconds,

until fragrant. Add the broccoli and cook for one minute. Next, add the

cabbage, cooking two minutes until cabbage wilts.

- Add the remaining 2 tablespoons broth and 1/4

teaspoon salt, red pepper flakes, and the oyster and soy sauces to the pan

and stir to combine.

- Stir the cornstarch slurry to recombine before

adding it to the pan. Coat the vegetables with the sauce and cook an

additional minute until slightly thickened. Top with the mushroom mixture.

- Serve with either white or brown rice.

|

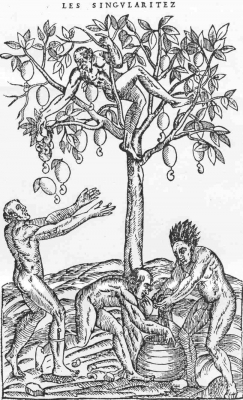

Image Credits (top to bottom):

Anacardium occidentale. ©2020 Steven

Foster

First known illustration of a cashew tree by André Thevet. 1558.

Anacardium occidentale. ©2020 Steven

Foster

Anacardium occidentale. ©2020 Steven

Foster

Anacardium occidentale. ©2020 Steven

Foster

References

- Anacardiaceae.

Encyclopedia Britannica. Available at: www.britannica.com/plant/Anacardiaceae. Accessed on September 21, 2020.

- Cashew. Encyclopedia

Britannica. Available at: www.britannica.com/plant/cashew#ref194103.

Accessed on September 21, 2020.

- Cashew. New World

Encyclopedia. Available at: www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Cashew. Accessed on September 21, 2020.

- National Geographic Society. Edible: An Illustrated Guide to the World’s

Food Plants. Lane Cove, Australia: Global Book Publishing; 2008.

- Morton J. Cashew

apple. Fruits of Warm Climates. Available at: www.hort.purdue.edu/newcrop/morton/cashew_apple.html. Accessed on September 22, 2020.

- Griffin L, Dean L.

Nutrient composition of raw, dry-roasted, and skin-on cashew nuts. Journal of Food Research.

2017;6(6)13-28.

- Kluczkovski A,

Martins M. Cashew nut. In: Caballero B, Finglas P, Toldra F, eds. Encyclopedia

of Food and Health. Manaus, Brazil: Federal University of Amazonus; 2016:683-686.

- Tufail T, Saeed F, Ain H, et al. Cashew nut allergy; immune health challenge. Trends in Food Science & Technology.

2019;86:209-216.

- Mah E, Schulz J, Kaden V, et al. Cashew consumption reduces total and LDL

cholesterol: A randomized, crossover, controlled-feeding trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

2017;105:1070-1078.

- Mohan V, Gayathri R, Jaacks L, et al. Cashew nut consumption increases HDL

cholesterol and reduces systolic blood pressure in Asian Indians with type 2 diabetes:

A 12-week randomized controlled trial. The Journal of Nutrition.

2018;148:63-69.

- Baer D, Novotny J.

Consumption of cashew nuts does not influence blood lipids or other markers of

cardiovascular disease in humans: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition.

2019;109:269-275.

- Cashew nut. USDA Food

Data Central. Available: https://fdc.nal.usda.gov/fdc-app.html#/food-details/170162/nutrients. Accessed

on October 2, 2020.

- Stir-fried vegetables

with toasted cashews. Food and Wine. September 2012. Available at: www.foodandwine.com/recipes/stir-fried-vegetables-toasted-cashews. Accessed on October 2, 2020.

- Bauman H, Darby S.

Food as Medicine: Broccoli (Brassica oleracea, Brassicaceae).

HerbalEGram. 2016;13(3). Available at: http://cms.herbalgram.org/heg/volume13/03March/FoodAsMedicine_Broccoli.html.

Accessed October 5, 2020.

|