Issue:

105

Page: 46-55

Maca Madness: Chinese Herb Smugglers Create Chaos in the Peruvian Andes

Consequences for the market, consumers, and local farming communities

by Tyler Smith

HerbalGram.

2015; American Botanical Council

Editor’s note:* This is an updated version of an article that first appeared in the December 2014 issue of HerbalEGram. Accompanying the original article is a special video report filmed for the American Botanical Council (ABC) by the “Medicine Hunter” and maca expert Chris Kilham. The video was recorded on November 4, 2014, in Peru’s Junín Plateau, where Kilham was conducting fieldwork and research on the current maca situation on behalf of Naturex, a major global supplier of plant-based extracts. Kilham’s video can be viewed on ABC’s YouTube page at www.youtube.com/user/HerbalGram/.

For more than three millennia, inhabitants of Peru’s central highlands have been cultivating the maca plant (Lepidium meyenii, Brassicaceae) for use as both food and medicine.1 The tuberous vegetable thrives in the harsh, dry climate of the Junín and Pasco provinces in the Peruvian Andes at elevations of up to 15,700 feet (approximately three miles) above sea level, where few other plants grow besides alpine grasses and bitter potatoes (Solanum spp., Solanaceae).1 At first glance, the maca plant may appear unremarkable. A member of the mustard family, the herb is similar in size and shape to a radish (Raphanus sativus, Brassicaceae), and mature plants grow to an average height of just four-to-eight inches. Below ground, maca forms a thick, bulbous hypocotyl, or tuber, that is rich in micronutrients and beneficial phytochemicals.1,2

Touted by news media and businesses as a superfood, maca’s popularity has exploded in the past decade. In November 2013, Mehmet Oz, MD, included the herb on his “Hot List” of energy-boosting foods,3 and maca is now commonplace in health food stores, smoothie shops, and major retail chains. According to HerbalGram’s 2013 Herb Market Report, maca was among the year’s 30 best-selling herbs in the mainstream multi-outlet channel, exhibiting a remarkable 150% increase in sales from the previous year.4

Maca’s recent surge in popularity is perhaps most evident in China, where the herb is prized for its libido-enhancing effects and its reputation as a source of longevity. Such appealing claims have led to an unprecedented demand for the herb in China, a country of 1.3 billion people.5 In May 2014, rumors began to surface of Chinese businessmen posing as tourists to illegally smuggle the fresh root out of the country. As the maca harvest began to disappear over the summer, prices increased — then skyrocketed.

Although the sudden popularity of this once-obscure herb has been a boon for local farmers and communities in the Peruvian Andes, the unprecedented Chinese demand for maca — and subsequent smuggling of the nationally protected plant out of Peru — has created a “highly volatile” market ripe with uncertainty.6 In August 2014, the situation went from volatile to violent when a Chinese national reportedly was murdered in Peru’s maca country.

“The arrival of the Chinese buyers in the Peruvian Andes has caused extraordinary chaos,” explained Chris Kilham, Medicine Hunter and maca expert, who recently spent time in both China and Peru investigating the situation (email, November 4, 2014).

“Yesterday a Chinese maca buyer was shot dead in a field, and another was shot and badly wounded,” alleged Kilham, noting that his information came directly from a police officer in the area (email, November 5, 2014). Kilham says he witnessed the ambulance carrying the second gunshot victim away. “It is now fair to say that the situation is out of control. It has all become very dangerous.”

How the maca situation will unfold remains uncertain, but sources contacted for this article expressed a general lack of optimism. “As someone who loves high-quality Peruvian Maca and who has sold it for many, many years, I am very concerned,” noted Mark Ament, founder and owner of The Maca Team, a family-run Peruvian maca company based in Maryville, Tennessee (email, November 4, 2014). “Prices will likely continue to rise and the demand will possibly grow. If nothing is done to curb the Chinese, then we’ll likely have a similar shortage indefinitely.”

Maca’s Cultural Significance in Peru

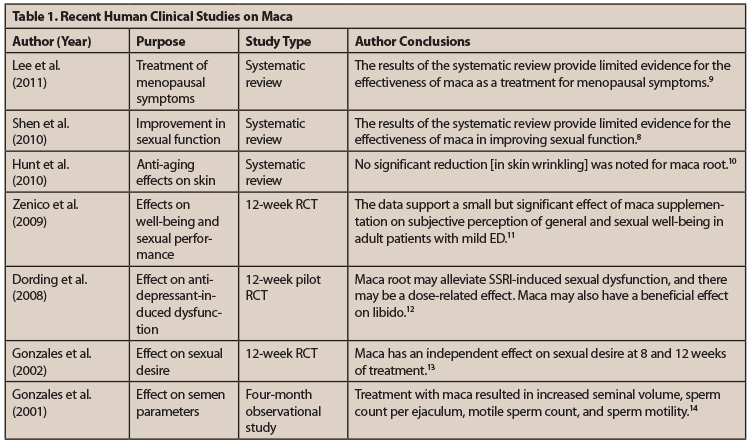

In Peru, maca has been used traditionally to treat a range of conditions, many of which are related to sexual dysfunction and lack of energy. The herb, for example, has been used to increase fertility and stamina, promote cognitive function, enhance libido, and reduce menopausal symptoms, among other functions.1,2,7 In recent years, several human clinical trials have lent support to some of these traditional medicinal uses (see Table 1). A systematic review of four randomized, controlled trials in 2010, for example, concluded that maca significantly affected erectile dysfunction in men and improved other types of sexual dysfunction in both men and women.8

Many of those living in the maca-producing regions of Peru depend almost entirely on income derived from the season’s harvest, which takes place from roughly May to October, the winter months of the South American country. In addition to relying on the herb for their livelihoods, Peruvians in the central highlands regularly consume maca, which is considered a staple food in the region.

“For the Andean people, maca is life. It is an absolutely essential food, as [almost] nothing else grows up at high altitude,” wrote Kilham. “The plant … is a source of great cultural pride.”

In an effort to protect maca’s heritage, the Peruvian Minister of Justice issued a regulation in 2003 officially banning the export of unprocessed raw maca.15 Two years after the export ban was established, the National Commission for Native Peruvian Products recognized maca root as one of the country’s first “flagship” products as part of a “national strategy to protect and promote Peruvian native crops … of a recognized authentic quality that should be preferred by external markets.”15

Most recently, Peru’s National Institute for the Defense of Competition and Protection of Intellectual Property (INDECOPI) developed a Designation of Origin specification and certification for the protection of Peruvian maca grown and processed according to traditional methods in the provinces of Junín and Pasco. The government of Peru followed up this national initiative by registering a Maca Junín-Pasco Appellation of Origin with the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO).16

“Maca is considered to be a natural genetic heritage product of Peru,” wrote Ament (November 7, 2014). “Attempts to grow it outside of Peru legally should be approved by the Peruvian government. China does not have this approval and therefore the Maca they grow is grown under biopiracy conditions.”

Quality and Quantity: Issues with Chinese-Grown Maca

The numerous titles, designations, and legal protections assigned to maca, however, apparently are not enough to prevent the prized plant and its seeds from being smuggled out of Peru. In June 2014, Peru’s Association of Exporters (Associacion de Exportadores, or ADEX) reported that seven patents related to maca processing had been filed in China. Through interviews, ADEX was able to determine that four of the patent holders’ plant materials originated in Peru.17,18† The rest of the maca in question was from China.

“China has been cultivating maca in [the] Yunnan province for about ten years now,” Kilham stated, “but the altitude there is lower than in the Peruvian highlands. Thus the maca must be grown with pesticides, herbicides, etc., and with commercial fertilizers, in contrast to the high altitude Peruvian maca, which is produced with no agritoxins at all.”

Ament notes a number of important distinctions between Peruvian and Chinese-grown maca on The Maca Team’s website.19 In addition to potential issues with chemical contamination and the toxic growing conditions in China (Ament, speaking to Modern Farmer, referred to the Yunnan province as a “chromium dump”18), adulteration is listed as a primary concern.

Gaia Herbs, Inc., a major botanical products company based in North Carolina, already has begun testing samples of Chinese-grown maca products for evidence of contamination or adulteration. Recently, Gaia tested a sample of Chinese maca powder submitted for analysis by an Asian company.

“[T]here was definite intentional adulteration as indicated by the lack of any viable DNA from their sample,” explained Bill Chioffi, vice president of global sourcing at Gaia (email, December 3, 2014).

“The HPLC [high-performance liquid chromatography] profiles of the Asian Maca powder and our validated reference of Peruvian Maca were similar, although the amplitude of the peaks in the Asian maca were much lower indicating a weaker product,” Chioffi added. “If you relied solely on these tests, which most companies do, you would be fooled into believing that you had true Maca. … It is sophisticated adulteration that’s going on.”

Such intentional adulteration has the potential not only to tarnish the image of reputable companies but also to impact the effectiveness of such products. “If China is able to flood the market with their … subpar Maca at cheaper prices, many potential new customers are likely not to get the normal benefits associated with Maca,” Ament wrote, “and thereby write off the product’s efficacy in general” (email, November 24, 2014).

On The Maca Team’s website, Ament has posted side-by-side images of Chinese and Peruvian-grown maca.19 The differences are stark. The Peruvian tuber is a deep red color with symmetrical roots; the Chinese-grown maca plant is dark and twisted.

The observable differences between Peruvian and Chinese-grown maca, and potential safety concerns associated with the latter, have not stopped Chinese companies from aggressively pursuing maca cultivation in their country. Currently, Peru has more than 6,000 acres of land dedicated to maca farming.20 Maca plantations in China occupy an estimated 10,000-15,000 acres, although Chinese officials have denied the accuracy of that figure.21

Even though China has two-to-three times more land dedicated to maca than Peru, Chinese consumers’ demand for Peruvian maca has shown no signs of decline. “The Chinese with whom I spoke while in China very much want high altitude Peruvian Andean maca,” wrote Kilham. “And apparently they are willing to pay for it.”

Chinese Smugglers Arrive in Peru

Chris Kilham has been following the maca trade since the late 1990s, when he first met Sergio Cam, the owner of Chakarunas Trading Company in Peru, which supplies maca to Naturex, where Kilham is employed as its sustainability ambassador. (Appropriately, Chakarunas is related to the Quechua word for “men who build bridges between cultures.”22)

“Since Sergio and I began this maca journey in 1998, the maca market has bloomed steadily, and has grown well and without major mishap, up until this year,” he wrote (email, November 4, 2014).

Kilham took multiple research excursions to Peru in 2014 in an effort to monitor the rapidly changing market and shifting dynamics on the ground. He first encountered Chinese buyers in the Andes back in May, shortly before the 2014 maca harvest began. Through interviews and conversations with police, officials, farmers, and others, Kilham has become well informed of — and, in some cases, witnessed — the deteriorating situation in Peru and its impacts over the past year.

“[A]fter 16 years of relative stability, groups of Chinese buyers arrived in the highlands, and started snatching up maca anywhere they could get it,” he recalled. “The Chinese buyers include Red Dragon Triad crime syndicate members out of Hong Kong,” claimed Kilham. “They are armed, and carry large sacks of cash.”

Although Spanish-language newspapers and television stations in Peru have featured occasional updates of the illegal botanical smuggling activities taking place in the past year, the first official acknowledgement of the situation by a government organization came in a June 2014 press release from ADEX.23

Citing evidence of maca seeds smuggled by Chinese nationals out of Peru, ADEX Natural Products Committee Chair Alejandra Velazco denounced the illegal activity, calling it an act of biopiracy. According to an article from the International Trade Centre, Velazco claimed “that a large number of Chinese buyers have been present in Peru this summer making advance cash payments directly with maca farmers but informally without proper transaction and export documentation, evading taxes and violating other Peruvian laws concerning maca.”15

Just a few months after ADEX’s announcement, Diane Panella, formerly of the California-based natural products company Sol Raiz Organics, contacted the American Botanical Council after one of her company's Peruvian maca suppliers informed her of the situation in Peru.

“A contingent of men from China have taken up residency in the province and are aggressively trying to control the maca trade,” Panella wrote. “[O]ne of our maca shipments was run off the road and the driver severely injured and hospitalized” (email, October 2, 2014).

Kilham, who most recently visited Peru in early November, described a generally chaotic and increasingly dangerous situation on the ground.

“The Chinese are still scouring the highlands post-harvest, snatching up any and all maca. A number of Chinese buyers hid from us when we sought them out, and some sped off when we approached their vehicles,” he recalled (email, November 11, 2014). “Just this week, Red Dragon Triad members murdered a restaurant owner in Peru who refused to pay shakedown money. It’s right out of a bad kung fu movie.”

Peru’s Response, or Lack Thereof

The government of Peru’s response to the allegations of illegal smuggling and biopiracy by Chinese nationals appears to be out of proportion with the value it places on maca, one of the country’s inaugural flagship products.

“[T]here appears to be nothing positive to report,” responded Ament when asked what actions were being taken to stop or prevent such illegal activity. “We are in contact with suppliers and friends in Peru very regularly, and it seems that next to nothing has actually been done to stop the practice of illegally purchasing and removing Maca roots from Peru.”

A peer reviewer of this article familiar with the situation, however, noted that shipping containers “at the Port of Callao near Lima, Peru have been ‘Red Flagged’ for inspection by Sunat [Peru’s National Customs and Tax Administration] to ensure that they do not contain ‘whole maca’ roots” (email, December 3, 2014). He added that the inspection process had caused a major delay with one of his company’s shipments.

In the more than half a year since the Chinese arrived in Peru allegedly to begin securing the 2014 harvest, only two enforcement actions by Peruvian officials have been covered widely by local media. (American media coverage had been almost non-existent until early December 2014, when the New York Times and Wall Street Journal published articles on the topic.20,24) In late September, Peruvian officials seized a large shipment of maca that Chinese individuals were planning to smuggle across the northern border. The container, simply labeled “Flowers,” contained more than 10 tons of maca, valued at approximately $1 million.25 Shortly thereafter, Peru’s Interior Minister Daniel Urresti announced that 200 foreigners had been deported in the preceding three weeks. “Peru promotes tourism,” said Urresti in an article from Peru’s Gestion newspaper, “but [we] will not allow foreign citizens [to] break the rules.”25

Still, given the limited publicized actions Peru has taken to address — or even monitor — the biopiracy of one of its treasured natural resources, it is difficult to take Urresti’s claims seriously. The lack of official government action even prompted criticism from the former president of ADEX, José Luis Silva Martinot. “The Chinese are taking maca without paying taxes,” he said in an August 19, 2014, article from El Comercio. “Where is Sunat and other authorities?”21

Impacts on Companies and Consumers

The time for a swift government response, it seems, has passed. Effects of China’s “hijacking” of the 2014 maca harvest are being felt at almost every point in the supply chain, from Peruvian farmers and entrepreneurs to natural products companies and consumers in the United States.18 Maca prices hover at uncomfortably high levels, and the market remains unstable.

“Because so little was done to curb the rapid export of Maca this year, the 2014 harvest of Peruvian Maca is 95% gone,” Ament estimated. “The harvest, which finishes in September, normally lasts until the following June/July. This year, as of late October it is next to impossible to purchase Peruvian-grown Maca.”

Sol Raiz Organics founder Ken Stittsworth, who has been in the maca-growing regions of Peru since late November 2014, expressed similar concerns. “As far as my company goes, I’m subjected to much higher prices now,” he wrote (email, November 24, 2014). “At the moment, we’re just weathering the storm” (email, December 15, 2014).

Small, family-run businesses such as Ament’s and Stittsworth’s, however, are not the only companies affected by the situation in Peru. “Naturex, Gaia Herbs, Navitas, and the many other companies who have relied on maca for years are now facing an absurd escalation of prices,” Kilham noted, “which surely will sit poorly with customers.”

If such rapid price escalation continues, it has the potential to “collapse the maca market,” Kilham warned. “Is anybody really going to pay $60-$80 US for a 12 ounce bag of maca powder? … We are getting into the rarified ethers of pricing.”

And, according to Ament, American consumers can already smell the fumes. “US consumers are already affected by this,” he said. “We, for example, have raised our prices 25% ([our company’s] first price increase in over 5 years).” The Maca Team — which has exhausted its supply of premium maca product and expects to sell out of other products by early 2015 — alerted its customers to a second, unavoidable price increase in December.

“This situation will certainly price some customers who benefit from Maca out of the market,” Ament said. “We’ve already had several customers express that.”

Panella of Sol Raiz Organics also has been forced to face an unpleasant reality as a result of the chaotic maca market. “I am on indefinite hiatus from the company since Oct. 1 because of the financial constraints being created by this problem,” she wrote (email, November 19, 2014). “This is a company that I love and believe in passionately, so I am hoping for a positive outcome someday to the situation.”

Impact on Peruvian Farmers and Communities

According to Peru’s National Anti-Biopiracy Commission (chaired by INDECOPI), 120 companies are actively involved in the country’s maca production, and approximately 100,000 Peruvians depend on maca for their economic livelihoods.26 Since it is illegal to export unprocessed maca from Peru, many such Peruvians find work during post-harvest processing. This year, however, up to an estimated 80% of the season’s maca harvest — which totaled 4,000 tons in 201323— was smuggled out of Peru.28

“While the farmers have done well this year, all other people associated with the production, marketing, and distribution of Maca have been cut out of the loop,” Ament explained. “Since the Chinese took the roots in their whole form, rather than in powder, [thousands] of people … are currently working less and may be out of work altogether.”

According to data from Peru’s Integrated Information System for Foreign Trade (SIICEX), maca exports for 2013 totaled $14 million 27 (The 2013 export figure was calculated for “maca products;” as noted previously, only processed maca raw material is legally permitted to be exported,15 but it is not clear if SIICEX’s number includes finished consumer products as well.) As depicted below, there was a particularly steep increase in the value of Peruvian maca exports to China in 2014 (Figure 1).29

There is big money in the Peruvian maca market, but even this year’s “gold rush” will not make millionaires of Peruvians farmers. In fact, concerns about food security may soon trump those of financial security.

“The people up there have modest means,” Kilham explained. “[W]hile growers are currently making absolutely wild money, maca is now un-affordable to non-growers, and thus an essential staple food is becoming out of reach for people who depend on it.”

Ament also expressed concerns about the long-term impacts and financial consequences for Peruvian farmers. “The farmers are in a tough situation here,” he said. “Most of them have sold all of their harvest now and while they have been paid more than normal for their produce, the money is soon spent.”

“There is an expression in Spanish, ‘pan hoy, hambre mañana,’ which basically means ‘feast today, famine tomorrow,’” Ament continued. “Some of these farmers, then, are not going to have more funds coming in for the next 8-10 months. Beyond that, what most of the farmers don’t understand is that China is attempting to dominate the world Maca market, which will potentially destroy their livelihoods.”

Challenges and Proposed Solutions

There remains a dearth of information related to any recent, current, or planned actions by the Peruvian government to combat instances of biopiracy and illegal smuggling such as those that have taken place over the past year. However, in a September 2014 meeting of Peru’s Ministry of Foreign Commerce and Tourism, two proposals were presented by government officials to address the future of maca.25,28 Although neither of the options would resolve any short-term issues, the ideas are a sign of progress.

The first proposal is to create a National Register of Maca, which would involve “fieldwork to collect and process information about the varieties of maca in all areas of production.” The detailed record could then be used by Peru’s National Anti-Biopiracy Commission to resolve future maca patent cases.30 Magali Silva Velarde-Álvarez, Peru’s Minister of Foreign Trade and Tourism, suggested creating a new government office “responsible for providing technical assistance to farmers and entrepreneurs dedicated to [maca].” The proposed group, ProMaca, “would foster partnerships through the implementation of best practices in international trade, collective marks, quality seals, … [and] ad hoc export route[s] for maca.”30

Instead of waiting on Peru to take measures to protect the heritage product, Ament decided to take a more proactive approach, drafting and gathering signatures for a petition to Peruvian officials expressing the urgency of the situation.

“We are organizing a petition to submit to the Peruvian authorities in hopes of something being done to protect the genetic heritage and global supply of Peruvian Maca,” Ament wrote. For more information, or to sign the petition, visit www.themacateam.com/save-peruvian-maca.31

Lessons & Predictions for the Future

Since the start of the annual Peruvian maca harvest in May, fortunes have been made and lives allegedly have been lost over the tiny, tuberous plant that has been cultivated in the Andes for thousands of years. The impacts of the sudden, unrivaled demand for maca in China extend beyond Peru’s rugged borders, with consequences for major international natural products companies, loyal, long-term employees of small businesses, and maca enthusiasts worldwide.

“The Chinese market can swallow entire global industries whole and not even burp,” Kilham offered when asked if there was a lesson to be learned from the maca mayhem in Peru (email, November 21, 2014). “We will see this with many types of consumer goods. It used to be that the US got everything. Now China is the big dog at the table, and we need to get used to it.”

As Stittsworth explained, “The story of maca really is a three-piece puzzle on a global stage where you have two super powers importing and harnessing medicinal products and a country like Peru where farmers can be blinded by money and the government won’t protect them” (email, November 23, 2014).

Chinese consumers have developed a taste for maca, and although the herb is thought to be the first botanical example of the massive and influential purchasing power of the country’s middle class,32 Kilham likely is correct that it will not be the last.

Some predict that China — which already dwarfs Peru in terms of acreage dedicated to maca cultivation — will dominate the global maca market in as little as one-to-three years.33 Chinese nationals already have begun preparing for the 2015 harvest of the Peruvian plant.

“We have heard from one of our main suppliers in Peru that next year there will be approximately double the amount of Maca harvested as there was this year,” Ament reported. “However, this same source has also told us that over [half] of that has already been purchased by Chinese individuals through back door deals.”

Thus, the future of Peruvian maca market — and those who depend on the herb as a source of medicine, sustenance, and livelihood — remains uncertain.

“My conclusion is that maca prices will continue to climb; we will see adulteration of maca and poor quality maca in the market; the pressure from the Chinese buyers will escalate; [and] more illegal activity is inevitable,” Kilham predicted. “[T]he effect of this on the current maca market could well cause it to crash, and the Andean people are going to have an increasingly difficult time securing maca for food. As far as I can figure, there is currently no silver lining to this cloud.”

*Throughout the production of this article, the American Botanical Council (ABC) has attempted to ensure the accuracy of all information contained herein. The statements and opinions presented by sources quoted herein do not necessarily reflect the opinion of ABC and, in some cases, may represent unsubstantiated or unconfirmed claims.

† English translations of Spanish-language sources were provided by Google.

References

- Smith E. Maca root: Modern rediscovery of an ancient Andean fertility food. Journal of the American Herbalists Guild. January 2004;1-3.

- Brinckmann J, Smith E. Maca culture of the Junín plateau. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2004;10(3):426-430.

- Dr. Oz’s Energy-Boosting Hot List. The Dr. Oz Show website. Available at: www.doctoroz.com/episode/energy-boosters-hot-list. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Lindstom A, Ooyen C, Lynch ME, Blumenthal M, Kawa K. Sales of herbal dietary supplements increase by 7.9% in 2013, marking a decade of rising sales: turmeric supplements climb to top ranking in natural channel. HerbalGram. 2014;103:52-56. Available at: http://cms.herbalgram.org/herbalgram/issue103/HG103-mkrpt.html?t=1408980803&ts=1408993085&signature=408ef98446a018144d01bb7a796915be. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- China: population. CIA World Factbook website. Available at: www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/geos/ch.html. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Kilham C. Buying fever grips Peru’s maca trade. Fox News. August 6, 2014. Available at: www.foxnews.com/health/2014/08/06/buying-fever-grips-perus-maca-trade/. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Maca. Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center website. Available at: www.mskcc.org/cancer-care/herb/maca. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Shin BC, Lee MS, Yang EJ, Lim HJ, Ernst E. Maca (L. meyenii) for improving sexual function: a systematic review. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2010;10(44). Available at: www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/10/44. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Lee MS, Shin BC, Yang EJ, Lim HJ, Ernst E. Maca (Lepidium meyenii) for treatment of menopausal symptoms: A systematic review. Maturitas. 2011;70(3):227-33. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21840656. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Hunt KJ, Hung SK, Ernst E. Botanical extracts as anti-aging preparations for the skin: a systematic review. Drugs Aging. 2010;27(12):973-85. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21087067. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Zenico T, Cicero AF, Valmorri L, Mercuriali M, Bercovich E. Subjective effects of Lepidium meyenii (Maca) extract on well-being and sexual performances in patients with mild erectile dysfunction: a randomised, double-blind clinical trial. Andrologia. 2009;41(2):95-9. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19260845. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Dording CM, Fisher L, Papakostas G, Farabaugh A, Sonawalla S, Fava M, Mischoulon D. A double-blind, randomized, pilot dose-finding study of maca root (L. meyenii) for the management of SSRI-induced sexual dysfunction. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(3):182-91. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18801111. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Gonzales GF, Córdova A, Vega K, Chung A, Villena A, Góñez C, Castillo S. Effect of Lepidium meyenii (MACA) on sexual desire and its absent relationship with serum testosterone levels in adult healthy men. Andrologia. 2002;34(6):367-72. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12472620. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Gonzales GF, Cordova A, Gonzales C, Chung A, Vega K, Villena A. Lepidium meyenii (Maca) improved semen parameters in adult men. Asian J Androl. 2001;3(4):301-3. Available at: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11753476. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Alleged smuggling of Peruvian maca planting stock to China. July 28, 2014. Market Insider. Available at: www.intracen.org/blog/Alleged-smuggling-of-Peruvian-maca-planting-stock-to-China/. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Peruvian Maca? Peruvian Ginseng? Chinese Maca? What’s in a name? Market Insider. June 2, 2014. Available at: www.intracen.org/blog/Peruvian-Maca-Peruvian-Ginseng-Chinese-Maca-Whats-in-a-name/. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Adex alert illegal purchase of tons of maca Chinese. RPP. June 23, 2014. Available at: www.rpp.com.pe/2014-06-23-adex-alerta-compra-ilegal-de-toneladas-de-maca-de-chinos-noticia_702574.html. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Spencer P. Hijacked Harvest: Peruvian Maca in Peril. Modern Farmer. October 13, 2014. Available at: http://modernfarmer.com/2014/10/hijacked-harvest-peruvian-maca-peril/. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Peruvian maca root powder vs. Chinese maca. The Maca Team website. Available at: www.themacateam.com/peruvian-maca-root-powder-vs-chinese-maca. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Neuman W. Vegetable spawns larceny and luxury in Peru. New York Times. December 6, 2014. Available at: www.nytimes.com/2014/12/07/world/americas/in-peru-maca-spawns-larceny-and-luxury.html?_r=0. Accessed December 9, 2014.

- Three ministers will go to Congress for smuggling maca China. El Comercio. August 19, 2014. Available at: http://elcomercio.pe/peru/lima/tres-ministros-iran-al-congreso-contrabando-maca-china-noticia-1750815. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Downie A. On a Remote Path to Cures. New York Times. January 1, 2008. Available at: www.nytimes.com/2008/01/01/business/worldbusiness/01hunter.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- ADEX denounced China for biopiracy maca seed. El Comercio. June 23, 2014. Available at: http://elcomercio.pe/economia/peru/adex-denuncia-china-biopirateria-semillas-maca-noticia-1738185. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Maher K, Kozak R. The latest superfood? Peru’s maca root. Wall Street Journal. December 3, 2014. Available at: www.wsj.com/articles/the-latest-superfood-perus-maca-root-1417567226?mod=WSJ_hp_RightTopStories. Accessed December 9, 2014.

- Peru has expelled 200 illegal aliens in the last three weeks. Gestion. October 6, 2014. Available at: http://gestion.pe/politica/peru-ha-expulsado-200-extranjeros-ilegales-ultimas-tres-semanas-2110506. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Peruvian maca is cultivated illegally in China. La Republica. June 24, 2014. Available at: www.larepublica.pe/24-06-2014/maca-peruana-es-cultivada-ilegalmente-en-china. Accessed December 8, 2014.

- Maca product exports by main company in US$ 2009-2014. Integrated Information System for Foreign Trade (SIICEX) website. Available at: www.siicex.gob.pe/siicex/apb/ReporteProducto.aspx?psector=1025&preporte=prodempr&pvalor=1934. Accessed December 9, 2014.

- Maca smuggling: the news has gone around the world. ProExpansion. August 6, 2014. Available at: http://proexpansion.com/es/articles/666-contrabando-de-maca-la-noticia-ha-dado-la-vuelta-al-mundo. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Maca product exports by main markets in 2014. Integrated Information System for Foreign Trade (SIICEX) website. Available at: www.siicex.gob.pe/siicex/apb/ReporteProducto.aspx?psector=1025&preporte=prodmerc&pvalor=1934. Accessed January 22, 2015.

- MINCETUR proposes to create ProMaca to protect Peruvian product. El Comercio. September 2, 2014. Available at: http://elcomercio.pe/economia/peru/mincetur-propone-crear-promaca-proteger-producto-peruano-noticia-1754155. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Save Peruvian Maca. The Maca Team website. Available at: www.themacateam.com/save-peruvian-maca. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- Schutz H. Huge influx of Chinese capital coupled with threat of violence seriously destabilizes maca trade in Peru, expert says. NutraIngredients-USA website. Available at: www.nutraingredients-usa.com/Markets/Huge-influx-of-Chinese-capital-coupled-with-threat-of-violence-seriously-destabilizes-maca-trade-in-Peru-expert-says. Accessed December 1, 2014.

- A Peruvian national treasure is being smuggled out of the country by Chinese. Australian Broadcasting Company News website. Available at: www.abc.net.au/radionational/programs/bushtelegraph/maca/5837938. Accessed December 1, 2014

|