Issue:

108

Page: 54-59

Amazonian Tribe Compiles 500-Page Traditional Medicine Encyclopedia

by Connor Yearsley

HerbalGram.

2015; American Botanical Council

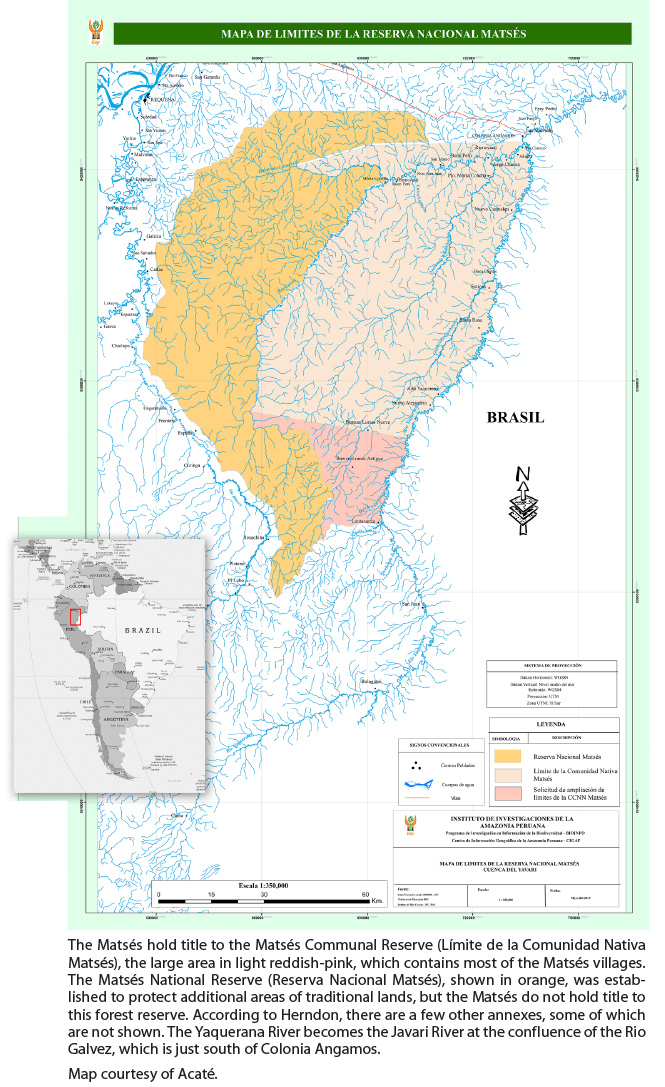

The Matsés, or Jaguar People, of Peru and

Brazil, who number approximately 3,300,1 have created a

comprehensive, 500-page encyclopedia of their tribe’s medicinal knowledge,

which was on the verge of being completely lost.2

The Matsés Traditional Medicine Encyclopedia is a compilation of the

rainforest medicinal knowledge (including knowledge of medicinal plants) of

five shamans and is written exclusively in the native language of the Matsés, which is also called Matsés. The tribe inhabits a large area

along the Peru-Brazil border and the Yaquerana and Javari rivers (see map).2

Since Amazonian peoples have

historically passed traditions down orally, this written record is believed to

be the first of its kind and scope. Granted, ethnobotanists have frequently

worked with indigenous peoples to catalog their herbal knowledge. For example,

the Huni Kuin people of the Brazilian state of Acre collaborated with an

ethnobotanist to publish a 260-page book about the healing power of plants.3 However,

the Matsés

encyclopedia is different in part because it was compiled without the aid of

ethnobotanists.

“That is what made this initiative so

revolutionary and the first of its kind. There were no outsiders coming in to

document [the Matsés’] knowledge, no expeditions, no translations. The entire encyclopedia

was written by the Matsés shamans in their own villages, in their own words, in their own

language, and through their worldview,” said Christopher Herndon, president and

co-founder of the conservation group Acaté, which collaborated on the conceptual

development and provided production and financial support for the project

(email, August 14, 2015).

The encyclopedia has not been translated

in order to prevent biopiracy, which is a real issue for the Matsés. For example, the skin secretions

of the giant monkey frog (Phyllomedusa bicolor) have mind-altering properties and

are used in Matsés

hunting rituals. After learning about the skin secretions, several

pharmaceutical companies and universities began conducting research and filed

for patents without regard for the Matsés.2 In addition, according to Herndon,

the Matsés

and the neighboring Matis tribe were the victims of another instance of

biopiracy: Hunters from the tribes traditionally have applied the milky

secretions of the bëcchëte plant (Tabernaemontana

undulata,

Apocynaceae) to their eyes to help them better distinguish textures. Seeds from

this plant can now freely be purchased on the internet.

The Matsés encyclopedia contains disease

names, symptoms, causes, the plants used as treatments, preparation

instructions, alternative therapeutic options, illustrations made by a young

Matsés artist, and

photos of every plant used in Matsés medicine. The photos, which were all taken by the Matsés, are not detailed enough to allow

outsiders to easily identify the plants, and no scientific names are provided

for the same reason.2 “The Matsés know the plants better than all of us and are highly

specific about how the plants are harvested, the maturity of the plants at

harvest, the parts of plants utilized and prepared, among other considerations.

This information is conveyed in the encyclopedia,” Herndon wrote.

This effort comes at a time when the

traditions of many Amazonian indigenous groups are quickly disappearing. In

fact, a renowned Matsés shaman died before his knowledge could be passed down, so Matsés leadership, along with Acaté (“acaté” is the Matsés taxon for the giant monkey frog1),

prioritized the creation of the encyclopedia before additional knowledge was

lost.2 According to Herndon, the project began in 2012, with

preliminary formative discussions beginning as early as July 2011, shortly

after the shaman’s passing.

The encyclopedia, which took more

than two years to complete, was written not only to conserve the knowledge of

the Matsés

elders, but also to help maintain the tribe’s self-sufficiency by preventing

the need for total reliance on outside medical solutions. Many Matsés cannot afford modern conventional

medicine and have only the most rudimentary access to it due to the tribe’s

remoteness. However, the encyclopedia is only the first step in Acaté’s three-step initiative.2

At the time the project was started,

none of the Matsés

shamans had apprentices to carry on their ancestral knowledge. Outside

influences, particularly missionaries, often convince younger members of

indigenous tribes that traditional medicine is primitive or altogether

unnecessary.2 In addition, young tribesman are pulled away by

the high-tech world, said José Fragoso, PhD, a research associate at the California Academy

of Sciences whose work focuses on the Neotropics. “They all unequivocally love gadgets

and the aura that surrounds material goods,” he said (email, August 13, 2015).

But most Matsés villages still rely on the few

remaining shamans (all of whom were trained prior to sustained contact with the

outside world). As a result, the second step of the process is for each elder

shaman, most of whom are over 60, to be accompanied in the forest by an

apprentice who will learn about the plants and assist in treating patients.2

The encyclopedia will serve as a

guide for these future shamans and will help bridge a generational gap. “Having the encyclopedia will

definitely help interest young [Matsés] in their culture,” said Dr. Fragoso, but there is still a

need to make it more appealing, “maybe by linking it to technological communication systems.”

Herndon pointed out though that there is no cellphone or regular electrical

access throughout most of the remote Matsés territories. Steven King, PhD, an ethnobotanist and

senior vice president of ethnobotanical research and sustainable supply at

Jaguar Animal Health, an ethnobotanically oriented drug discovery company, said

that having data to help validate the efficacy of the tribe’s herbal knowledge

(from a Western medical perspective) could also help encourage new apprentices

(email, August 13, 2015).

The Matsés decided that the apprenticeship

program, which started in 2014 in the village of Esitrón under the supervision of shaman

Luis Dunu Chiaid, should be expanded to as many villages as possible, with

special attention being given to villages that no longer have a shaman.2

The third step of Acaté’s initiative is for certain Western

medical practices to be integrated with and complement traditional Matsés

medicine. “It

is the idea of merging the best of both systems in a respectful and cooperative

manner. There are some health problems that can be managed well by both or

either system,” Dr. King said. For example, because of contact with the

outside, the Matsés,

like other indigenous peoples, have been exposed to foreign diseases such as

falciparum malaria.2 The Matsés tend to rely on outside medical

solutions to treat these introduced and more virulent forms of malaria,

according to Herndon.

The three-step initiative might have

broader implications for the rainforest the Matsés

inhabit. Acaté believes

that empowering indigenous peoples is the best way to preserve large tracts of

rainforest. In fact, many of the largest tracts of remaining rainforest are

inhabited by these tribes. Industries like mining, petroleum, and timber have

often taken advantage of tribes that have been weakened socially by outside influences,

have limited resources, or that have developed an increasing dependence on the

external world. The Matsés know that independence will make them and their home less

susceptible to falling victim to outside influences.2

In fact, Canadian oil company

Pacific Rubiales recently has become a threat to the Matsés. In

2007, Peru’s oil and

gas licensing body Perupetro granted the company licenses to two large tracts

of land on Matsés

territory. Many Matsés men have said they would fight with spears, bows, and arrows to

protect their land and the waters of the Yaquerana River. Logging, both legal

and illegal, is also a concern.4

Potentially at stake is one of the

most biodiverse regions in the world and the Matsés’ deep understanding of its vast

plant and animal resources. In Peru alone, the Matsés inhabit nearly three million acres

of rainforest on the eastern edge of the country.2 This area,

within the Peruvian region of Loreto, contains about two-thirds of the Matsés

population.1 To the south lies La Sierra del Divisor, a region containing many rare

plants and animals and uncontacted indigenous groups.2 Within

the Brazilian state of Amazonas,1 Matsés communities — which contain the

remaining one-third of the population — form the western edges of the Vale do

Javari, a reserve containing the largest number of uncontacted tribes in the

world.2 The Peruvian and Brazilian Matsés are completely separate

politically, but they intermarry and generally consider themselves to belong to

the same tribe. In Brazil, the Matsés are better known as Mayoruna,

although, according to Herndon, this term has also been used to refer to other

tribes in the region.1

The Matsés first established contact with the

Peruvian and Brazilian national cultures relatively recently, in 1969. Because

of that, and the tribe’s remoteness, they remain much more traditional than

other contacted indigenous groups in the area, and still obtain most of their

food by hunting, fishing, farming, and wild collecting. But now that they have

more motorized canoes and travel more frequently to the city of Iquitos and

Colonia Angamos (a Peruvian military outpost), they have more contact with

non-tribal Peruvians, and they are increasingly reliant on money to buy goods.

All Matsés

still speak their native language, and many of their traditional beliefs remain

intact. However, some young Matsés have lost pride in their culture. Some have even come to

resent it because of the racism of local non-tribal Peruvians and other

aforementioned factors. Others have left the tribe to work or join the army.

The three pillars of Acaté’s initiatives — sustainable economy, traditional

medicine, and permaculture — are meant to help stop and reverse that trend.1

Acaté also helps the Matsés sustainably harvest and market natural

products, such as copaiba resins (from trees in the genus Copaifera, Fabaceae) and sangre de grado (Croton

lechleri,

Euphorbiaceae), also known as dragon’s blood. This allows the tribe to earn

income and prevents them from having to take up destructive and dangerous

timber-cutting jobs.1

The Matsés are taking proactive steps toward

being able to determine their own fate and minimize the high rates of mortality

and disease common among indigenous groups. This initiative can serve as a

blueprint for other indigenous groups facing similar cultural erosion.2 “Any

and all efforts that help link the health of communities … to the health of

their environment can and should be replicated and/or modulated to serve the

needs of communities,” Dr. King said.

“I would like to see all indigenous

people produce similar encyclopedias. Letting others know the depth of

knowledge held by societies is the best way we have of maintaining our cultures

and showing our deep concern for others,” Dr. Fragoso said.

—Connor Yearsley

References

- Butler R. Helping the Amazon’s ‘Jaguar People’ protect their culture and traditional wisdom. Mongabay website. Available at: http://news.mongabay.com/2014/02/helping-the-amazons-jaguar-people-protect-their-culture-and-traditional-wisdom/. Accessed September 1, 2015.

- Hance J. Amazon tribe creates 500-page traditional medicine encyclopedia. Mongabay website. Available at: http://news.mongabay.com/2015/06/amazon-tribe-creates-500-page-traditional-medicine-encyclopedia/. Accessed August 4, 2015.

- Torres B. Projeto pioneiro apresenta a terapêutica dos índios Huni Kuin. Globo website. Available at: http://oglobo.globo.com/cultura/livros/projeto-pioneiro-apresenta-terapeutica-dos-indios-huni-kuin-13294443. Accessed August 6, 2015.

- Hill D. The truth behind the story on the ‘world’s oldest tree’ being cut down. The Guardian website. Available at: www.theguardian.com/environment/andes-to-the-amazon/2015/feb/26/the-truth-worlds-oldest-tree-cut-down. Accessed August 7, 2015.

- Intellectual property and traditional medical knowledge. World Intellectual Property Organization website. Available at: www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/tk/en/resources/pdf/tk_brief6.pdf. Accessed August 14, 2015.

- India foils UK firms’s bid to patent use of turmeric, pine bark and tea for

treating hair loss. Financial Express website. Available at: www.financialexpress.com/article/pharma/market-pharma/india-foils-uk-firmss-bid-to-patent-use-of-turmeric-pine-bark-and-tea-for-treating-hair-loss/122806/Google. Accessed August 31, 2015.

The Biopiracy Issue: To Document or Not to Document? Despite the Matsés past experiences with biopiracy, Dr. Fragoso thinks they may eventually consider translating the encyclopedia into other languages. “Once mechanisms are in place to ensure the information cannot be misused or stolen for commercial purposes, they may find a way to make it broadly available. The important, labor-intensive step of recording the information for posterity has been taken,” he wrote.

However, choosing to translate the encyclopedia could be a gamble for the Matsés. It is possible that doing so would allow them to take advantage of certain defensive protection options, like those made possible by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). For example, if the encyclopedia were made more broadly available, a “prior art” search could then preclude illegitimate patents. In other words, parties trying to file for patents could be denied if already-documented information prevented an invention from meeting the “novel” and/or “inventive” criteria necessary to be granted the patent.5 In fact, a recent patent application submitted to the European Patent Office (EPO) by Pangea Laboratories, Europe’s leading dermaceutical (a skin care product with claimed medicinal properties) laboratory, was thwarted.6 The company proposed making a hair-loss treatment using turmeric (Curcuma longa, Zingiberaceae), pine bark (Pinus spp., Pinaceae), and green tea (Camellia sinensis, Theaceae), but was denied when prior art evidence contained in the Traditional Knowledge Digital Library (TKDL), which digitally documents existing literature on four of India’s traditional medical knowledge systems,5 showed that formula as being a traditional hair-loss remedy in India’s Ayurvedic system of medicine.6

But documentation in repositories such as the TKDL provides no guarantees against misappropriation of traditional knowledge. The WIPO warns that documentation can sometimes destroy rights, as it does not prevent knowledge from being used by third parties and may, in fact, provide ideas for new inventions. If an invention meets the necessary criteria to be patented, it does not matter if traditional knowledge was the basis for the idea. Consulting the WIPO’s Traditional Knowledge Documentation Toolkit can help indigenous groups develop an intellectual property strategy when deciding to document their traditional knowledge.5 Whether the Matsés eventually decide to translate the encyclopedia or not, Dr. Fragoso said he thinks fear of biopiracy is actually hurting some indigenous peoples by preventing more collaborations like the one between the Matsés and Acaté. Dr. King said he also thinks fear of biopiracy can be detrimental. “At times, this concern has indeed stifled research, cooperation, medical exchange, and ultimately useful benefit-sharing out of paranoia,” he wrote. —Connor Yearsley

|