Issue:

108

Page: 42-53

Baobab: The Tree of Life —

An Ethnopharmacological Review

by Simon Jackson

HerbalGram.

2015; American Botanical Council

Since the origins of human

existence, people have looked to their natural surroundings for sources of

nutrition and health remedies. One of the authors (SJ), after traveling in many

parts of sub-Saharan Africa and talking to traditional healers in rural

communities, has found that the plants in one’s immediate vicinity often will

contain a surprising amount of constituents with nutritional and medicinal

benefits. One example is the baobab tree (Adansonia

digitata, Malvaceae), one of the largest sub-Saharan botanicals, which the author has

termed a “Cinderella species” — one that is often overlooked, but once properly

researched and examined, is shown to be a novel foodstuff with significant health

benefits. This article addresses some of the traditional nutritional and

medicinal uses, the chemical and pharmacological profile, and scientific facts

and myths of the iconic baobab tree.

INTRODUCTION

With its distinctive silhouette,

broad trunk, unusual root-like branches, and large, velvety fruit, baobab is

the best known of all African trees. The tree is steeped in legend, and due to

the many different uses of its various parts, it is known by the local people

as the “tree of life.” A large tree can hold up to 4,500 liters of water; its fibrous bark

can be used for rope and cloth; its edible leaves and fruit can provide relief

from sickness; and its hollow trunk can provide shelter for as many as 40

people.1 So, it is easy to see why it has earned this name.

There has been a renaissance of

ethnobotanical surveys of medicinal plants, especially in the cosmetics and

nutrition sectors where industry chemists and product formulators are

constantly looking for new and natural healthy ingredients.2,3 Since

its approval as a novel food ingredient by European Union (EU) food regulators

in 2008,4 the native African baobab tree has gained increasing

market and media exposure. This paper presents a study of the

ethnopharmacological uses of the tree in southern Africa and its significant

array of ethnobotanical and potential commercial uses.

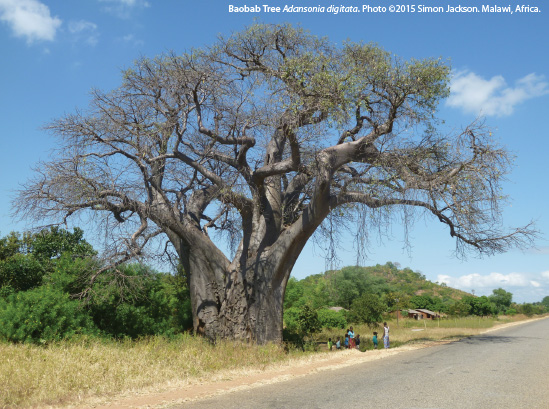

BOTANICAL DESCRIPTION

The baobab tree is also known as the

upside-down tree, boab, boaboa, bottle tree, kremetart tree, cream of tartar

(not to be confused with the multipurpose ingredient potassium bitartrate,

which is made from fermented grapes [Vitis vinifera, Vitaceae]) tree, or monkey bread

tree. The word “baobab” is derived from the Arabic bu hobab, meaning “fruit with many seeds.” There are eight species of baobab: six are indigenous to Madagascar, one to Australia, and one to mainland Africa (A. digitata). Adansonia

digitata grows in most countries south of the Sahara, although in South Africa it is restricted to the Limpopo and Mpumalanga provinces.5

A massive deciduous tree with a

round or spreading crown, it can grow to heights of 20 m (approximately 65 ft).

The trunk is stout, tapering, and abruptly bottle-shaped, and it can be up to

12 m (39 ft) in diameter. The bark is smooth, grayish-brown, and has heavy

folds. The bark on the lower part of the trunk often bears scars from local

people who harvest it to retrieve the strong fibers, and from elephants that

try to obtain water from the trees. However, even with trunk damage, baobab can

continue to grow and regenerate new layers of bark. The leaves are alternate

and palmately compound in mature plants. The flowers are waxy, white, crinkly,

and mostly solitary, growing up to 20 cm in diameter. The ovoid-shaped fruits

are roughly 15 cm long with a hard, woody shell covered by velvety hairs, and

they contain kidney-shaped seeds that are embedded in a powdery pulp. In

sub-Saharan Africa, baobab is harvested in April and May, and flowers are

harvested from November to December. The tree favors a dry, woodland habitat

with rocky, well-drained soil.

Baobab is a slow-growing tree and, as such,

there has been much speculation about the age of large trees and their growth

rate. Carbon-dating techniques and analyses of core samples suggest that baobab

trees with 10 m diameters may be around 2,000 years old.5

TRADITIONAL MEDICINAL USES

Baobab leaves, bark, and fruit are

used for food and medicinal purposes in southern Africa. The bark has

astringent properties and has been used traditionally to alleviate colds,

fevers, and influenza (a decoction made from the fresh bark is taken as a

beverage for one week to treat the flu).6 The wood, bark, and seeds

of the tree are known to have anti-inflammatory properties.7 The

leaves may be used as an antiperspirant, and they also have been used to treat

fever, kidney and bladder diseases, as well as asthma and diarrhea.8-14

In African traditional medicine, baobab fruit pulp is used to treat fever,

diarrhea, dysentery, smallpox, measles, hemoptysis (the coughing up of blood),

and as a painkiller. For the treatment of infant diarrhea, a mixture made from

the floury pulp mixed with millet flour and water is given to the child until

cured.8 For dysentery, baobab leaves are administered orally or

crushed into a drink. Leaves can also be used in hip-baths to treat parasitic

skin infections. The seed can be pulped and applied externally or added to

water as a drink to treat gastric, kidney, and joint diseases.15

During the rainy season when the

trees are in leaf, baobab is a good fodder tree, especially for game such as

elephants, kudus, nyalas, and impalas. At the end of the season, cattle eat the

fallen leaves, and various game species relish the fallen flowers. As far as

humans are concerned, the roots can be tapped for water, and the young roots

are cooked and eaten. Young leaves can be cooked and eaten like spinach or

dried and powdered to be used later. The leaves are rich in ascorbic acid

(vitamin C), sugars, and potassium tartrate.16 The acid pith of the

fruit is rich in vitamin C and can be used to make a refreshing drink. Baobab

seeds, the oil of which is high in calories, can be eaten fresh, dried, or

roasted as a substitute for coffee (Coffea spp., Rubiaceae). The pulp

and seeds have high nutritional value in the form of iron, calcium, and vitamin

C, and they can be fed to livestock toward the end of the dry season when

grazing is poor.

The citric and tartaric acids found

in the pulp inspired one of baobab’s popular names, “cream of tartar tree.” Baobab pulp

is often used in baking as a milk-curdling agent, as a flavoring for yogurt and

ice cream, and as a source of calcium for pregnant and lactating women. Due to

its high pectin content, the pulp also has been used traditionally as a

thickening agent for sauces and jams. In some African cultures, the pulp has

been used as an ingredient in cosmetics.17

Baobab has a long history of use as

a medicinal product. The botanist and physician Prospero Alpini (1553-1617)

wrote in his book De plantis Aegypti liber that fresh baobab fruit had a

very pleasing taste, and that the Ethiopians used it on burns and rashes and to

cool the effects of serious fevers. For these afflictions, they either chewed

the flesh of the fruit or pressed it into a juice with added sugar. Alpini also

wrote that in Cairo, Egypt, where fresh baobab fruit was unobtainable,

Egyptians made preparations from its powder to treat fevers, dysentery, and

bloody wounds — an indication that this plant has been used medicinally for

centuries.18

Local medicinal uses for baobab are

richly varied.15 The bark, along with dried leaves, is made into a

preparation called lalo that is used to induce sweating and reduce

fever. The bark contains a quantity of edible, insoluble, acidic,

tragacanth-like gum, which is used to disinfect skin ulcers and wounds. Mucilages

made from baobab phloem sap in the bark are used as a remedy for

gastrointestinal inflammation.15,19 The bark also is popular as a

cardiotonic; this traditional use has been confirmed experimentally by

researchers who demonstrated the positive inotropic effect of an ethanolic bark

extract on isolated atrial muscles of rats.20

In Sierra Leone specifically, the

leaves and bark are used as a prophylactic against malaria. In the Congo, a

bark decoction is used to bathe children with rickets, and in Tanzania, as a

mouthwash to treat toothache. In Ghana, the bark is used as a substitute for

quinine in cases of fever. In southern Zimbabwe, the leaf is eaten as a

vegetable, while in central Africa it is used as a diaphoretic (perspirant)

against fevers, and the seeds as a remedy for dysentery. In Messina, South

Africa, the powdered seed is given to relieve hiccups in children.1

In Nigeria and Senegal, baobab

fruits are reputed to be effective against microbial diseases. This has been

confirmed in tests against certain bacteria and fungi, although the active

constituents responsible for these effects have yet to be isolated.21

A prepared root infusion is used as a bath for babies to maintain soft skin.20

Conditions including asthma, sedation, colic, fever, inflammation, diseases of

the urinary tract, ear trouble, backache, wounds, tumors, and respiratory

difficulty are treated orally. The leaves are considered an emollient and

diuretic, and leaf decoctions are used for earache and otitis (inflammation of

the outer ear, middle ear, or ear canal).15 In general, leaf

preparations are used for the control of kidney and bladder diseases, asthma,

fatigue, and as a tonic, blood cleanser, prophylactic, and febrifuge (a

medication that reduces fever). They have also been used for diarrhea,

inflammation, insect bites, the expulsion of guinea worms, internal pain, and

other afflictions.

BIOLOGICAL PROPERTIES

The pulp of baobab fruit contains

astringent compounds (e.g., tannins and cellulose), which exert an

antidysenteric action due to an osmotic effect and an inhibitory interaction

with acetylcholine, the neurotransmitter that is responsible for gut spasms.

The fruit has anti-inflammatory, febrifuge, and analgesic properties due to the

presence of saponins and sterols; experimental data have also shown the fruit

to have hepatoprotective effects.20 The leaves have both

antihypotensive and antihistaminic properties, and the leaf powder, due to its

antihistaminic properties, has been suggested as an anti-asthmatic.22

Anticancer

Activity

Anticancer activity is virtually

unheard of in plants in the family Malvaceae, yet research suggests that A.

digitata may have

antitumor properties.1 In Senegal and Guinea, both a decoction and a

poultice made from baobab fruit extract were shown to have antitumor

activities.23,24 The specific bioactive constituents responsible for

these actions have not yet been identified.

Antisickling

Activity

Sickle-cell anemia is a problem that

has affected Africans for centuries. One Nigerian remedy is derived from a

concoction of an aqueous extract of the bark of A. digitata, which is used locally for its

antisickling activity. However, after testing various concentrations on washed

sickle-cell blood samples, researchers in Nigeria found that the results did

not support the anecdotal reports.25

Hepatoprotective Influence

In vitro studies in Saudi Arabia

have shown that aqueous extracts of A. digitata pulp demonstrate hepatoprotective

activity against carbon tetrachloride administered in rats. Consumption of

certain Adansonia fruits may play an important role in human resistance

to liver damage. The mechanism of action for liver protection is unknown, but

it may be due to the triterpenoids, beta-sitosterol, beta-amyrin palmitate,

alpha-amyrin, and/or ursolic acid in the fruit.26

Antiviral,

Antibiotic, Anti-inflammatory, Antipyretic, and Analgesic Effects

Researchers in Togo, western Africa,

and Canada studied 19 medicinal plants of Togo and analyzed them for antiviral

and antibiotic activity. Of the 19 species studied, 10 demonstrated significant

antiviral activity, and all but two showed antibiotic activity. A.

digitata was the

most potent, exhibiting activity against each of the three tested viruses

(herpes simplex, Sindbis, and polio).27 Further antimicrobial tests

undertaken in Nigeria confirmed the aforementioned results.21

Aqueous extracts of baobab fruit

have exhibited marked anti-inflammatory, antipyretic (in rats given 400 and 800

mg/kg dosages), and analgesic (in mice two hours after administration) effects.28,29

Phytochemical examination has revealed the presence of sterols, triterpenes,

saponins, tannins, and glycosides, which may play a role in these actions.

Other studies support baobab’s

anti-inflammatory and antiviral activities as well. In one experiment, baobab

leaves, fruit pulp, and seeds were extracted with three different solvents:

water, methanol, and dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).7 Researchers

compared the three extracts to determine the minimum concentration required to

inhibit 100% of three viruses (herpes simplex, influenza, and respiratory

syncytial virus), and assessed their effects on cytokine secretion (interleukin

[IL]-6 and IL-8) in human cell cultures. Cytokines are cell-signaling proteins

that play an important role in the immune system. The leaf extracts

exhibited the most potent antiviral properties, particularly the DMSO extracts,

and the influenza virus was the most susceptible virus. Pulp and seed extracts

were less active but still showed significant results. Cytotoxic activities of

the extracts were evident only at much higher concentrations. Additionally, the

researchers found that the extracts — particularly the leaf extracts — acted as

cytokine modulators, meaning that they possessed anti-inflammatory activity.

Overall, the results indicate the presence of multiple bioactive compounds in

different parts of the plant, which may explain some of the medical benefits

attributed to traditional leaf and pulp preparations. These promising results

highlight the urgent need for more scientific research to be conducted on the

baobab tree.

Antioxidant

Capacity

Epidemiological evidence has linked

intake of vitamin C and other antioxidant micronutrients to health benefits, by

virtue of their capacity to trap reactive oxygen species (ROS) that are

associated with degenerative diseases and damage to biological systems.30

Current scientific evidence has helped boost consumer interest in supplementing

the diet with antioxidants, especially those derived from natural sources.

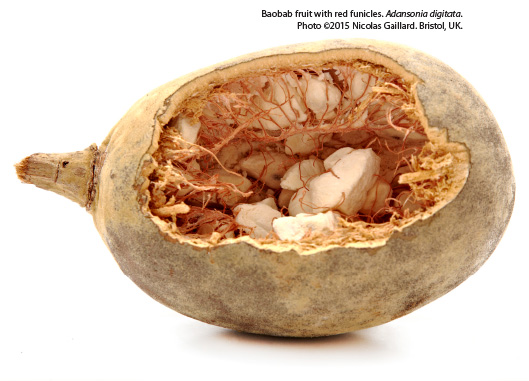

Baobab fruit pulp is a valuable source of vitamin C, while baobab leaves

contain provitamin A.13 The red funicles (threadlike stalks that

connect seeds to the ovary wall) present in the fruit have an impressive

antioxidant capacity, higher than in other parts of baobab and in many other

fruits as well (Table 1).12,31 However, the exact antioxidant

composition in baobab has not yet been determined.

The method most widely used to

measure antioxidant activity involves generating radical species and analyzing

the antioxidants that cause the disappearance of these radicals. The scavenging

activity of antioxidants is measured against a reference compound, such as

Trolox, a water-soluble equivalent of vitamin E. Most published antioxidant

activity investigations conducted on baobab have focused on fresh leaves only.12

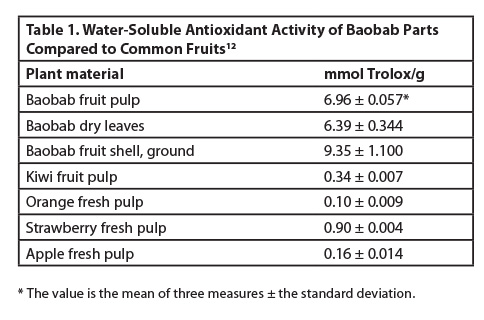

Vertuani et al. investigated the

fresh fruit pulp, fruit shell, and dry leaves of baobab and compared the

antioxidant values to those of other commonly consumed fresh fruits with high

levels of vitamin C, including orange (Citrus sinensis, Rutaceae), kiwi

(Actinidia chinensis, Actinidiaceae), apple (Malus

domestica, Rosaceae),

and strawberry (Fragaria × ananassa, Rosaceae).12 In this study,

antioxidant activity was measured with a photochemiluminescence method of

aqueous/methanol extracts from baobab products. This method allows for the

measurement of the antioxidant capacities of both water- and lipid-soluble

components. In water-soluble fractions, antioxidants such as flavonoids and

vitamin C can be detected, while in lipid-soluble fractions, tocopherols and

carotenoids can be measured.32,33 Baobab products displayed the

highest capacity. Notably, dry leaves exhibited an antioxidant capacity of

approximately 6.4 mmol (millimoles) of Trolox equivalents per gram of tested

product (Table 1). In comparison to the baobab fruit pulp, kiwi,

orange, strawberry, and apple all showed a much lower antioxidant capacity.12

However, comparing fresh fruit to dry fruit is misleading since baobab

fruit is naturally dry, but these figures represent the best data available,

and are a fairly good indication of baobab’s antioxidant capacity.

With regard to the lipid-soluble

antioxidant component, baobab fruit pulp also showed the highest antioxidant

capacity (4.15 mmol/g), followed by the dry leaves (2.35 mmol/g). The other

fruit pulps had very limited capacity, which may be due to their low levels of

lipid-soluble antioxidants.12

To account for the potential effects

of secondary antioxidant products, and to avoid underestimation of antioxidant

activity, the oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) assay can be used to

follow reactions for extended periods of time. With this method, values are also

reported as Trolox equivalents. Seasonal variation in fruit products, different

methods of extraction, and treatment of samples can lead to differences in the

outcome values. Absolute ORAC values are more significant when the test

materials are in the same condition.31

In a study using ORAC values to

compare the antioxidant capacities of baobab and so-called “superfruits” (Baobab Foods, unpublished data,

2011), the baobab red funicle was found to contain the highest level of

antioxidants compared to goji berry (Lycium barbarum, Solanaceae),

pomegranate (Punica granatum, Lythraceae), and cranberry (Vaccinium

macrocarpon,

Ericaceae), with the exception of the açaí berry (Euterpe oleracea, Arecaceae). Baobab fruit pulp has

an ORAC value twice as high as those of cranberry and pomegranate. These data

suggest potential antioxidant benefits from the consumption of

baobab-containing products, although these results have been difficult to

replicate and validate.

In a separate study of African

fruits and culinary spices, A. digitata fruit once again showed high

antioxidant capacity along with the highest amount of total phenolics (237.68

mg gallic acid equivalents/g) and total flavonoids (16.14 mg vitamin E/g) of

the botanicals tested.34 Researchers reported IC50 (the half

maximal inhibitory concentration) values of 8.15 µg/mL and 9.16 µg/mL using the

DPPH (a standard antioxidant assay using 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) and

ABTS (an enzyme assay using 2,2′-azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic

acid)) assays, respectively. The FRAP (ferric reducing ability of plasma) assay

determined a Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity of 0.75 mmol/g.

CONSTITUENTS

Small Molecules

Acids, terpenoids, and flavonoids

Adansonia

digitata fruit

contains organic acids such as citric, tartaric, malic, and succinic acids, and

its seeds yield oil that contains oleic, linoleic, and linolenic acids, as well

as cyclopropenic fatty acids.8,16 Baobab also contains terpenoids,

such as α- and β-amyrin palmitate, β-sitosterol, and ursolic acid.

In the 1980s, researchers in India

identified two new flavonol glycosides from the roots of A.

digitata, namely

3,7-dihydroxy flavan-4-one-5-O-β-D-galactopyranosyl (1→4)-β-D-glucopyranoside

from the benzene extract of the water-insoluble fraction of the ethanolic root

extract, and quercetin–7-O-β–D-xylopyranoside from spectral data and chemical

studies of an ethyl acetate stem extract.35,36 Further investigation

has identified another flavanone glycoside, fisetin-7-O-α-L-rhamnopyranoside,

in the roots of baobab.37

Macromolecules

Polysaccharides

Published research has shown that

baobab fruit pulp contains sugars but no starch and is an excellent source of

vitamin C, calcium, and pectin. The fruit pulp is composed of carbohydrates

(75%), proteins (2.5%), and a limited amount of lipids.20 It also

contains fibers (50%), both soluble and insoluble, which are composed mainly of

pectin. Pectin levels range from 23.4-33.8 mg/100 g depending on

varieties and geographical location.38,39

Recently, researchers have focused

on the potential gut health benefits associated with pectin, which exhibits

health-promoting properties in the gastrointestinal tract. This polysaccharide

has shown potential as a prebiotic, as it enhances the growth of probiotic

bacteria in the large intestine. Studies have shown that pectin prevents

pathogenic bacteria from binding to the intestinal wall, and that it chelates

heavy metals, which are then excreted through urine.40-42

Adansonia

digitata’s leaves

and bark have been reported to contain an alkaloid called adansonin, which is

used as an antidote to strophanthin, a poisonous cardiac glycoside alkaloid

that is present in vines of the genus Strophanthus (Apocynaceae). This

is important to locals since strophanthin is used as an arrow poison in Africa.

Previously, adansonin was sold as a substitute for quinine due to its febrifuge

properties.43,44 However, it is not clear whether adansonin is a

pure compound or if it is indeed an alkaloid. It is possible that the substance

is a mixture of compounds, but more structural research is needed. Baobab

leaves are also rich in mucilage that contains uronic acids, rhamnose, and

other sugars.

Micronutrients

Minerals and trace elements

Calcium, potassium, magnesium, and

iron are abundant in baobab.38 In general, it is rare for calcium to

be found in large quantities in fruits and vegetables, but baobab dried fruit

pulp contains large amounts of this micronutrient, ranging from 257-370 mg/100

g. The leaves contain even greater amounts (307-2640 mg/100 g dry weight).45

These quantities rival those of other good dietary sources of calcium — for

example, dried skim milk (960-1890 mg/100 g) — but it is much higher than

levels present in other fruits and vegetables.16 Baobab contains

four times the amount of calcium found in dehydrated apricots (Prunus

spp., Rosaceae), and 13 times that in dehydrated apples.46 Whether

or not the calcium is in a form suitable for absorption via oral administration

is currently under review.

Baobab dried fruit pulp also has the

highest concentration of potassium, magnesium, copper, and manganese among

popular dehydrated fruits, and the second-highest concentration of zinc. The

magnesium content of baobab is similar to that of dehydrated bananas (Musa

acuminata, Musaceae), whereas iron levels are comparable to those found in

dehydrated apricots and peaches (Prunus persica, Rosaceae).38 Based on the

European Recommended Daily Allowances (RDAs) for calcium, iron, and magnesium

of 800 mg, 14 mg, and 375 mg, respectively, baobab powder could prove to be a

useful dietary source of these minerals, provided that sufficient amounts could

be added to a product to enable a label claim. In order to make an

on-label claim in Europe, the product must contain 15% of the RDA of the

vitamin or mineral per 100 g, or per single-serving package.16,46

Vitamins

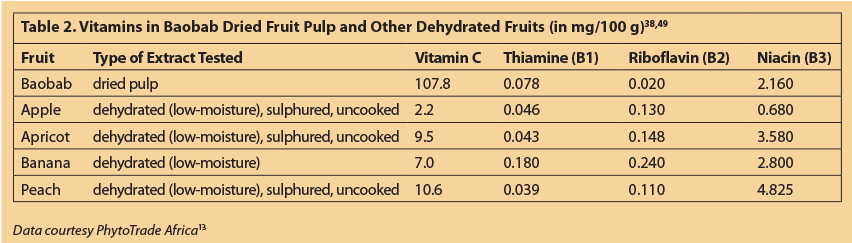

The main vitamins found in baobab

include vitamin C and various B vitamins. On average, baobab ripe pulp has a

vitamin C content of approximately 107 mg/100 g, which will remain stable for months

if protected from moisture. Even if no precautions are taken, appreciable

quantities of the vitamin will endure in the pulp for many years. One study

found that baobab ripe pulp stored in a glass bottle showed no signs of

bacterial or fungal decomposition after two years.47

Baobab dried fruit pulp contains

significantly higher levels of vitamin C than other commonly consumed dried

fruits16 (Table 2). Obtaining the dried pulp traditionally involves

minimal processing, which helps preserve heat- and moisture-sensitive vitamins.

Vitamin C is present in an amount of about 300 mg/100 g of dried fruit pulp15

— six and a half times higher than that of oranges (46 mg/100 g), five times

higher than that of strawberries (61 mg/100 g), and 10 times higher than that

of dried peaches and apricots.9,38 Baobab fruit pulp, naturally in

powdered form, contains levels of vitamin C ranging from 34-499 mg/100 g.

(According to the unofficial African Herbal Pharmacopoeia, such levels depend on the source,

with pharmacopeial-grade material containing the largest amounts.48)

Based on the European RDA of 80 mg of vitamin C, baobab fruit pulp powder added

to an ingestible product could provide an adequate daily source of vitamin C.

In a study that assessed the vitamin

B1 (thiamine) and B2 (riboflavin) contents in A. digitata, the leaves were found to contain

higher levels of vitamin B2 than vitamin B1, with the most vitamin B2 (1.04 ± 0.05

mg/100 g dry matter) found in baobab leaves from Senegal. The highest iron

content (26.39 mg/100 g) was found in leaves from Mali.45

Macronutrients

Fiber

In terms of macronutrients, baobab

dried fruit pulp is low in fat and consists of approximately 50% fiber. It is

relatively low in protein but contains numerous amino acids.16

Baobab dried fruit pulp therefore would be ideal as a fiber-supplementing

ingredient in foods, raising the overall nutritional profile. According to the

EU Nutrition and Health Claims Directive (No. 1924/2006), a claim that a food

is a source of fiber may be made only if the product contains a

minimum of 3 g/100 g, or at least 1.5 g/100 kcal.50A claim that a

food is high in fiber may be made only if the product contains a minimum

of 6 g/100 g, or at least 3 g/100 kcal. No specific information is available on

the glycemic index (GI) or satiating effects of baobab, but its profile,

compared to other foods, would indicate that it may have the potential to be a

low-GI and satiating ingredient due to its low sugar and high soluble fiber

content.43,51

Baobab vs. Superfruits:

Comparing Nutritional Content

To date, the oft-used marketing term

“superfruit” does

not have an official regulatory definition, but products marketed as

superfruits are generally high in a variety of nutrients and thus are

associated with health benefits. Fruits currently marketed as superfruits

include açaí

berry, blueberry (Vaccinium spp.), cranberry, goji berry, mangosteen (Garcinia

mangostana, Clusiaceae),

and pomegranate, and some have suggested adding baobab to the list as well.

When comparing the micronutrients

found in baobab to those found in superfruits, one must take into account that

values for baobab are for the dried fruit pulp, whereas the data for

superfruits are for raw foods. The vitamin C content of baobab dried fruit pulp

is up to five times higher than that of raw blueberries and 15 times higher

than that of pomegranates. It has much higher levels of niacin (vitamin B3),

slightly higher levels of vitamin B1, and about the same amount of vitamin B2

as the selected superfruits. Baobab dried fruit pulp has also been found to

contain greater quantities of calcium, magnesium, and iron. It is worth noting

that removing water from fresh fruit concentrates the nutrients, so it may be

an unfair comparison. However, as baobab is naturally dry, the situation is

unavoidable.

In summary, baobab fruit pulp has

the following:

Vitamins B1 and B2, and a high

natural vitamin C content (at least 100 mg/100 g);

Strong antioxidant properties with

an Integral Antioxidant Capacity of 11.1 mmol/g, which is significantly higher

than that of orange pulp (10.2 mmol/g) and grape seed oligomers (10.25 mmol/g);

Minerals, including calcium (293

mg/100 g), phosphorus (96-118 mg/100 g), iron (7-8.6 mg/100 g), and potassium

(2.31 mg/100 g);

Low amounts of fat and high levels

of soluble fiber;

High levels of pectin, making it a

useful binding and thickening agent;

Organic acids such as ascorbic,

citric, malic, and succinic acids, which contribute to baobab’s bitter taste.

COMMERCIAL USES

Nutritional

Applications

Since baobab obtained approval from

EU regulators in 2008 as a novel food ingredient, the United Kingdom has been

increasing imports of powdered baobab fruit for use as a healthy additive to

snack foods and beverages. In the UK, the amount of baobab dried pulp that can

be added to foods, such as cereal bars and smoothies, ranges from 10-20%

(typically 5-10 g).16 This should be kept in mind when assessing

baobab’s contribution to the product’s overall nutritional intake.

A 2008 report by the UK-based

Natural Resources Institute estimated that trade in baobab fruit could be worth

up to $961 million per year for African producers — it is currently valued at

$11 million.13 African producers export approximately 20 tons of

baobab each year, and the growing industry is crucial in bringing money to

local people who harvest and process the fruit.

Baobab fruit pulp is currently

available as a milled and sifted, free-flowing, light-colored powder, as well

as a de-pectinized extract, and in the form of leaf extracts, fruit fiber

(funicles), or fruit seed oil. The powder can be taken in its pure form as is

done traditionally, but it can also be stirred into porridge, yogurt, or

smoothies to appeal to a Western diet. Companies in Europe and North America

offer baobab food products in a variety of forms, including sauces, jams, bars,

and fruit chews, among others.

Skin

and Cosmetic Benefits

In addition to its nutritional

value, baobab has been shown to be beneficial for skin care. Studies suggest

that baobab preparations can promote skin cell regeneration and tone, tighten,

and moisturize the skin.17,20,52 These effects may be due, in part,

to baobab’s vitamin A, D, and E content. The fruit pulp provides a complex of

vitamins that exerts a variety of positive, synergistic actions, including the

following: emollient effects (vitamin A), the control of sebaceous gland

excretion (vitamin B6), the induction of melanin synthesis (vitamin B1/B2

complex), antioxidant defense and collagen synthesis stimulation (vitamin C),

improvement of cutaneous circulation (vitamin B4), action against lipid

peroxidation (vitamin E), and defense from tissue matrix degradation

(triterpenic compounds).20

Fiber contained in the pulp also

promotes anti-aging and antioxidant effects on the skin. Leaf extracts have

antioxidant, emollient, and soothing properties, keeping skin soft and elastic

while also exerting antibacterial activity. The fatty oil from the seeds

improves the firmness, hydration, and lightness of the skin. It also has soothing

and anti-inflammatory effects due to essential oils, hydrocarbons, and sterols,

making it an ideal treatment for dry skin and the prevention of wrinkles.

Baobab seed oil can heal abrasions, sunburns, and hematomas, and promote tissue

regeneration.17

CONTAMINANTS & ADULTERANTS IN BAOBAB DRIED

FRUIT PULP

Foreign

Matter and Silicon

Baobab fruit is sustainably

wild-harvested and the fruit pulp is separated from the other unwanted parts of

the fruit. This process can potentially introduce contaminants into the baobab

dried fruit pulp from two sources: extraneous matter, such as soil, and

endogenous matter, such as seed and plant fiber.

To quantify these potential sources

of contamination, one of the authors (SJ) of this article analyzed samples of

baobab dried fruit pulp to determine levels of both foreign matter and silicon

(Jackson et al., unpublished data, 2013). The analysis found less than 0.026%

of extraneous and endogenous matter (by weight) in tested samples of dried

fruit pulp, which suggests that the producers used proper collection and

handling practices. An acid-insoluble ash test (a method used to gauge the

purity of a substance53) found silicon levels of 0.1 g/100 g baobab

dried fruit pulp. This result suggests that there were no significant problems

with soil, sand, or diatomaceous earth contamination during or after harvest.

Suppliers can address potential

contamination issues (e.g., excess levels of foreign matter, pesticide

residues, heavy metals, microbes, or mycotoxins) by adhering to the US Food and

Drug Administration’s (FDA’s) current Good Manufacturing Practices (cGMPs). The baobab

fruit pulp samples tested by the author were screened for each of these

contaminants using the methods published in the African Herbal

Pharmacopoeia.48

Botanical

adulteration may be the result of accidental or intentional contamination.

Microscopic analyses can help identify foreign matter in samples. For example,

researchers can learn more about the quality of a sample by simple microscopic

observation using a polarizing filter and chloral hydrate, or iodine, which

reveals any added starch grains.

Intentional

adulterants (e.g., ascorbic acid) are sometimes added to fortify samples or

make the raw material or extract appear more valuable. If ascorbic acid were

added to a sample, for example, analyses would show abnormally high values of

vitamin C (more than 500 mg/100 g). The authors and their colleagues have

tested at least three different samples from various suppliers in different

countries, and are confident in the results shown (Jackson et al., unpublished

data, 2013).

Microbial Levels

In order to

assess potential microbial contamination, the author tested baobab dried fruit

pulp (in duplicate) for several microbial organisms, including E. coli,

fecal Streptococci, and Salmonella (Jackson et al., unpublished data,

2013). The results were within the range that is generally accepted in

cGMP guidelines for limits of microbial contamination (i.e., less than 1,000

colony-forming units [cfu]/g). E. coli, Staphylococcus aureus, fecal Streptococci, and

yeasts were below the limit at which the numbers of the colonies are counted; Salmonella was not detected in the samples.

Finally, both the total viable count and mold-produced colony counts ranged

between 2,600 and 7,800 cfu/g. These counts are not unduly high or unexpected

in a fruit that is wild-harvested and processed by a simple mechanical

separation.

Pesticide Residues

The data in

Table 3 show the results of a multi-residue pesticide analysis on the baobab

dried fruit pulp. The results are presented in terms of the pesticide class

rather than the individual pesticide, and the data clearly show that pesticide

residues are below the limits of detection. These results are to be expected,

as pesticides are not used at any stage during the growing or harvesting of

wild-harvested baobab fruit.

Heavy Metals

The author (SJ)

also analyzed three samples of baobab dried fruit pulp in duplicate for the

presence of four heavy metals: arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury (Jackson et

al., unpublished data, 2013). The levels of arsenic, cadmium, and mercury in

the baobab dried fruit pulp samples were all below the detection limits (Table

4). Only lead was detected (at levels much lower than acceptable limits

established by European food guidelines).54

Mycotoxins and Related Substances

The baobab

dried fruit pulp samples were also analyzed in duplicate for mycotoxins, and

the results are shown in Table 5. In each of the samples, the amount of total

aflatoxins was below the limit of detection.

Summary: Contaminants & Adulterants

In all of

these categories, the levels of potential food contaminants were found to be

acceptable and unlikely to cause harm to consumers. According to the analyses

performed by the author, the levels of pesticide residues and mycotoxins were

below the limits of detection. Three out of four of the heavy metals analyzed

were also below the limits of detection, and the content of lead was well below

permitted safety limits. Additionally, the foreign matter content of the baobab

dried fruit pulp was found to be less than 0.026% by weight, the microbial

contamination level was in the acceptable range, and the total viable count and

mold levels were low. It warrants mention that only a small number of samples were

tested, and testing for possible contamination and/or adulteration of material

from other commercial sources was not performed.

CONCLUSION

The fruit of A. digitata is nutritious and could have

significant value as an ingredient in functional foods, dietary supplements,

and skincare products, and as a novel source of anti-inflammatory and antiviral

compounds. In addition, the vitamins and oils derived from baobab can be highly

beneficial for skincare products due to their moisturizing, healing, and skin-regenerating

effects.

Baobab is rich

in vitamins and minerals, containing more than 100 mg vitamin C per 100 g of

dried fruit pulp — higher than many other fruits. If added to a product in

sufficient quantities, baobab could satisfy label claims as a source of vitamin

C (12 mg or 15% of the RDA) in the UK market. The presence of vitamin C

combined with its iron content may make baobab an effective optimizer of iron

uptake. The African botanical is also a good source of calcium (317 g/100 g),

iron (5.94 g/100 g), and magnesium (148 g/100 g) compared to other fruits.

While the amount of baobab in consumer products (typically up to 20%) may be

insufficient to claim it as a source of these minerals, baobab still can

contribute to a product’s total mineral

content.

Based on its

ORAC values, baobab fruit pulp has a higher antioxidant capacity than many

berries — twice as high as those of pomegranate and cranberry. This is an added

selling point for baobab, as consumers are increasingly interested in products

high in antioxidants, and manufacturers have developed a variety of antioxidant

superfood products, such as drinks and foods containing goji berry,

pomegranate, or açaí.

Finally, since

the potential contaminants of baobab are classified as avoidable contaminants,

they should either not be present or be present at such low levels as to pose

no health risk to consumers.

Simon Jackson, PhD, graduated from

the King’s College Department of Pharmacognosy with a doctorate in bioactive

natural products of sub-Saharan African origin. He has spent subsequent years

studying uses of African medicinal plant species. Dr. Jackson has since set up

the Natural Products Community (NPC) Research Foundation to promote the study

and commercialization of African indigenous plant extracts.

Anabel Maldonado received her

BSc at York University in Canada and is a London-based editorial and

copywriting consultant who works across lifestyle and health topics. Her

interests span beauty, nutrition, skin care, natural products, mental health,

and the biological basis of behavior.

Disclosure

Dr. Jackson is the founder and CEO

of Dr. Jackson’s Natural Products, which specializes in African-based cosmetic

and herbal preparations. Some of these products contain baobab.

References

- Wickens GE. The Baobabs: Pachycauls of Africa, Madagascar and Australia. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Science & Business Media; 2008.

- Ashidi JS, Houghton PJ, Hylands PJ, Efferth, T. Ethnobotanical survey and cytotoxicity testing of plants of southern-western Nigeria to treat cancer, with isolation of cytotoxic constituents from Cajanus cajan Millsp. J Ethnopharmacol. 2010;128:501-512.

- Li JW, Vederas JC. Drug discovery and natural products: end of an era or an endless frontier? Science.2009;325:161-165.

- Commission Decision of 27 June 2008 authorising the placing on the market of baobab dried fruit pulp as a novel food ingredient under Regulation (EC) No 258/97 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Official Journal of the European Union. 2008;183:38-39. Available at:

http://acnfp.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/mnt/drupal_data/sources/files/multimedia/pdfs/commdec2008575ec.pdf.

Accessed October 8, 2015.

- Baum DA, Small RL, Wendel JF. Biogeography and floral evolution of baobabs (Adansonia, Bombacaceae) as inferred from multiple data sets. Syst Biol. 1998;47(2):181-207.

- Sulaiman LK, Oladele OA, Shittu IA, Emikpe BO, Oladokun AT, Meseko A. In-ovo evaluation of the antiviral activity of methanolic root-bark extract of the African baobab (Adansonia digitata Lin). African Journal of Biotechnology.2011;10(20):4256-4258.

- Vimalanathan S, Hudson, J. Multiple inflammatory and antiviral activities in Adansonia digitata (baobab) leaves, fruits and seeds. Journal of Medicinal Plants Research. 2009;3(8):576-582.

- Lockett CT, Calvert CC, Grivetti LE.

Energy and micronutrient composition of dietary and medicinal wild plants

consumed during drought. Study of rural Fulani, northeastern Nigeria. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition. 2000;51(3):195-208.

- Lunven P, Adrian J. Intérêt alimentaire de la feuille et de la pulpe du fruit de baobab (Adansonia digitata). Ann Nutr. 1960;14:263-276.

- Obizoba IC, Anyika JU. Nutritive value of baobab milk (gubdi) and mixtures of baobab (Adansonia digitata L.) and hungry rice, acha (Digitaria exilis) flours. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 1994;46(2):157-165.

- Nour AA, Magboul BI, Kheiri NH. Chemical composition of baobab fruit (Adansonia digitata L). Trop Sci. 1980;22:383-388.

- Vertuani S, Braccioli E, Buzzoni V, Manfredini S. Antioxidant capacity of Adansonia digitata fruit pulp and leaves. Acta Phytotherapeutica. 2002;V:2. Available at: www.baobabfruitco.com/pdf/Pdf/2008/2003_02_ActaPhytoTerAntioxidant.pdf.

Accessed October 21, 2015.

- Phytotrade/LFR summary report. Nutritional evaluation of baobab dried fruit pulp and its potential health

benefits. London, UK; July 2009.

- Sidibe M, Williams JT. Baobab. Adansonia digitata.

International Centre for Underutilised Crops: Southampton, UK; 2002.

- Kamatou GPP, Vermaak I, Viljoen AM. An updated review of Adansonia

digitata: a commercially important African tree. South African Journal of Botany. 2011;77(4):908-919.

- Food Standards Agency. McCance and

Widdowson’s The Composition of Foods. 6th ed. Cambridge, UK: Royal Society

of Chemistry; 2002.

- Vermaak I, Kamatou GPP, Komane-Mofokeng B, Viljoen AM, Beckett K. African seed oils of commercial importance — cosmetic applications. South African Journal of Botany. 2011; 77(4):920-933. Available at: www.researchgate.net/profile/Guy_Paulin_Kamatou/publication/236011534_African_seed_oils_of_commercial_importance__Cosmetic_applications/links/00b49515ad9885ba8b000000.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2015.

- Alpini, P. De Plantis Aegypti. Venice; 1592.

- Mueller MS, Mechler E. Medicinal Plants in Tropical Countries. New York, NY: Thieme Medical Publishers; 2004.

- Burlando B, Verotta L, Cornara E, Bottini-Massa E. Herbal Principles in Cosmetics – Properties and Mechanism of Action. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2010.

- Hussain HSN, Deeni YY. Plants in Kano ethnomedicine: screening for antimicrobial activity and alkaloids. Int J Pharmacognosy. 1991;29(1)51-56.

- Hostettmann K, Marston A, Ndjoko K,

Wolfender JL. The potential of African plants as a source of drugs. Current

Organic Chemistry. 2000;4:973-1010.

- Sebire, RPA. Les Plantes Utiles du Senegal. Paris;1899:341.

- Kerharo J, Adam JG. La Pharmacopée Sénégalaise Traditionelle — Plantes Médicales et Toxiques. 1974.

- Adesanya SA, Idowu TB, Elujoba A. Antisickling activity of Adansonia digitata. Planta Med. 1988;54(4):374.

- Qarawi A, Damegh M, Mougy S. Hepatoprotective influence of Adansonia digitata pulp. Journal of Herbs, Spices

& Medicinal Plants. 2003;10(3):1-6.

- Ananil K, Hudson JB, De Souzal C, et

al. Investigation of medicinal plants of Togo for antiviral and antimicrobial

activities. Pharmaceutical Biology. 2000;38(1):40-45. Available at: http://stipulae.johnvanhulst.com/DOCS/PDF/InvestigationAntiviralActivity_MedicinalPlantOfTogo.pdf. Accessed October 21, 2015.

- Kaboré D, Sawadogo-Lingani H, Diawara B, Compaoré CS, Dicko MH, Jakobsen M. A review of baobab (Adansonia digitata) products:

effect of processing techniques, medicinal properties and uses. African

Journal of Food Science. 2011;5(16):833-844.

- Ramadan, A. Harraz F, El-Mougy, S. Anti-inflammatory, analgesic and antipyretic effects of the fruit pulp of Adansonia digitata. Fitoterapia. 1994;65:418-422. Available at: www.mightybaobab.com/scientific-papers/Anti-Inflammatory-OralToxicity-BaobabPulp.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2015.

- Elsayed NM. Antioxidant mobilization in response to oxidative stress: a dynamic environmental-nutritional interaction. Nutrition. 2001;17:828-834.

- Nutrient Data Laboratory, Agriculture Research Service, US Department of Agriculture. Oxygen radical absorbance capacity (ORAC) of selected foods. 2007. Available at: www.functionalfood.org.tw/fodinf/food_inf970220-1.pdf. Accessed October 7, 2015.

- Popov I, Lewin G, Baehr R. Photochemiluminescent detection of antiradical activity. I. Assay of superoxide dismutase. Biomed Biochem Acta. 1987;46:775-779.

- Osman MA. Chemical and nutrient analysis of baobab (Adansonia digitata) fruit and seed protein solubility. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2004;59(1):29-33.

- Dzoyem JP, Kuete V, McGaw LJ, Eloff JN. The 15-lipoxygenase inhibitory, antioxidant, antimycobacterial activity and cytotoxicity of fourteen ethnomedically used African spices and culinary herbs. J Ethnopharmacol.2014;156:1-8.

- Chauhan JS, Kumar S, Chaturvedi R. A new flavanonol glycoside from Adansonia digitata roots. Planta Med. 1984;50:113.

- Chauhan JS, Chaturvedi R, Kumar S. A new flavonol glycoside from the stem of Adansonia digitata. Indian J Chem. 1982;21(B):254-256.

- Chauhan JS, Kumar S, Chaturvedi R. A new flavanone glycoside from the roots of Adansonia digitata. Nat Acad Sci Lett. 1987;10:177-179.

- Chadaré F, Linnemann A, Hounhouigan J, Nout M, Van Boekel MA. Baobab food products: a review on their composition and nutritional value. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2009;49(3):254-74.

- Brown L, Rosner B, Willett WW, Sacks FM. Cholesterol-lowering effects of dietary fiber: a meta-analysis. American Journal of Clinical Nutrition. 1999;69:30-42

- Rhoads J, Manderson K, Hotchkiss AT, et al. Pectic oligosaccharide mediated inhibition of the adhesion of pathogenic Escherichia coli strains to human gut culture cells. Journal of Food Protection. 2008;71:2272-2277.

- Schols HA, Visser RGF, Voragen AGJ, eds. Pectins and Pectinases. Wageningen, Netherlands: Wageningen Academic Publisher; 2009.

- Liu LS, Fishman ML, Hicks KB. Pectin in controlled drug delivery. Cellulose. 2007;14(1):15-24.

- Bamalli Z, Abdulkarim SM, Hasanah MG, Karim R. Baobab tree (Adansonia digitata L) parts: nutrition, applications in food and uses in ethno-medicine — a review. Annals of Nutritional Disorder and Therapy. 2014;1(3):1-9.

- Gebauer J, El-Siddig K, Ebert G. Baobab (Adansonia digitata): a review on a multipurpose tree with promising future in the Sudan. Die Gartenbauwissenschaft. 2002;67:155-160.

- Hyacinthe T, Charles P, Adama K, et al. Variability of vitamins B1, B2 and minerals content in baobab (Adansonia digitata) leaves in

East and West Africa. Food Sci Nutr. 2015;3(1):17-24.

- Souci SW, Fachmann W, Kraut H. Food Composition and Nutrition Tables. 6th ed. Stuttgart, Germany: Medpharm Scientific Publishers, CRC Press; 2000.

- Carr WR. The baobab tree: a good source of ascorbic acid. Central African Journal of Medicine. 1958;4(9):372-374. Available at:

http://opendocs.ids.ac.uk/opendocs/bitstream/handle/123456789/6462/Carr,%20W.R.%20%20CAJM%20%20vol.%204,%20no.%209.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed October 21, 2015.

- Brendler T, Eloff JN, Gurib-Fakim A, Phillips LD, eds. African Herbal Pharmacopoeia. Port Luis, Republic of Mauritius: Association for African Medicinal Plant Standards; 2010:7-13.

- Sena LP. Analysis of nutritional components of eight famine foods of the Republic of Niger. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition. 1998;52:17-30.

- Commission regulation (EC) No 1924/2006 of 20 December 2006 on nutrition and health claims made on foods. Official Journal of the European Union. 2006;404:9-25. Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:404:0009:0025:EN:PDF. Accessed September 14, 2015.

- Coe SA, Clegg M, Armengol M, Ryan L. The polyphenol-rich baobab fruit (Adansonia digitata L.) reduces starch digestion and

glycemic response in humans. Nutr Res. 2013;33(11):888-896.

- Tanabe H. Cosmetic composition. Japanese patent 2008-127281. 2008. Available at: www.directorypatent.com/JP/2008-127281.html. Accessed October 19, 2015.

- Starwest Botanicals most important quality assurance tests. Starwest Botanicals website. Available at: www.starwest-botanicals.com/content/quality_assurance.html. Accessed October 19, 2015.

- Commission regulation (EC) No

1881/2006 of 19 December 1006 setting maximum levels for certain contaminants

in foodstuffs. Official Journal of the European Union. 2006;364:5-24.

Available at: http://eur-lex.europa.eu/LexUriServ/LexUriServ.do?uri=OJ:L:2006:364:0005:0024:EN:PDF. Accessed September 14, 2015.

|