Issue:

112

Page: 46-59

Kratom: Medicine or Menace?

by Connor Yearsley

HerbalGram.

2016; American Botanical Council

In the United States, a proposed regulatory action on two

compounds found in the Southeast Asian herb kratom (Mitragyna speciosa,

Rubiaceae) has generated considerable public, professional, and media interest.

In a notice of intent published in the Federal Register on August 31, 2016, the

US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) announced the temporary listing of the

kratom alkaloids mitragynine (MG) and 7-hydroxymitragynine (7-OH-MG) in

Schedule I of the Controlled Substances Act (CSA) of 1970. The CSA defines

Schedule I controlled substances, which include heroin, LSD, and marijuana (Cannabis

spp., Cannabaceae), as “those that have a high potential for abuse, no

currently accepted medical use in treatment in the United States, and a lack of

accepted safety for use under medical supervision.”1-3

The temporary scheduling, which would have taken effect on

September 30, was “necessary to avoid an imminent hazard to the public safety,”

according to the DEA.1 But backlash from the public and members of Congress

prompted the DEA to announce on October 13 that it would withdraw its original

notice of intent and allow for a public comment period through December 1,

2016. The DEA also stated that it would receive from the US Food and Drug

Administration (FDA) a scientific and medical evaluation and scheduling

recommendation for the compounds.4,5

After the public comment period, the DEA could decide to

permanently place the compounds in a schedule of the CSA, which would require

an additional period for lawmakers and the public to comment, or it could

decide to move forward with the temporary scheduling that was originally

proposed, which would not require an additional comment period.4,5

The proposed temporary scheduling would have lasted for two

or three years. Under the CSA, a substance meeting the statutory requirements

for temporary scheduling may be placed only in Schedule I.1

The placement of the compounds in Schedule I, in effect,

would mean that possession and distribution of any preparations of kratom, a

plant that has shown the potential to help wean recovering addicts off heroin

and other addictive and dangerous opioids, would be illegal and could result in

criminal prosecution.6,7 Notably, cocaine and methamphetamine are currently

listed in Schedule II, meaning that, unlike Schedule I substances, physicians

can prescribe or administer these substances.3,8

Kratom is a tropical evergreen, broad-leafed tree native to

peninsular Thailand, southeastern Myanmar, Malaysia, Borneo, Sumatra, the

Philippines, and New Guinea. The herb is in the same family (Rubiaceae) as

other economically and medicinally important plants, including coffee (Coffea

arabica), gardenias (Gardenia spp.), and trees in the genus Cinchona (e.g., C.

officinalis and C. pubescens).9 Preparations of kratom leaves have been used

for centuries in Southeast Asia for a wide range of purposes, including as an

opium and alcohol substitute; to treat cough, diarrhea, and diabetes; to manage

pain, opioid withdrawal, and sexual dysfunction; and to stave off fatigue.6,10

In addition, the leaves have been applied to wounds and used as a vermifuge (an

agent that expels parasitic worms), and as a local anesthetic.9

Leaf preparations of the plant, including powders and teas,

act on the central nervous system. At low doses, they produce “cocaine-like” stimulant

effects, while higher doses produce “morphine-like” sedative and intoxicating effects.6

Therefore, some workers, such as seafarers, farmers, and rubber-tappers, in

southern Thailand, northern Malaysia, and elsewhere chew the fresh leaves to

increase work productivity and reduce fatigue during the day, and to relax

after work.9,11

Kratom, which started gaining popularity in the United

States within the last 15 years, has received increased media attention lately.

Although some people have successfully used kratom to recover from opioid and

alcohol addictions, there has been growing concern about the addictive

potential of kratom itself. The DEA notice repeatedly refers to kratom’s

potential for abuse.1

The DEA’s scheduling proposal comes in the midst of an

unprecedented opioid epidemic in the United States. For example, in 2012, there

were 12 states with more opioid prescriptions than residents. The ratio was the

largest in Alabama, where there were 142.9 opioid prescriptions per 100 people,

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).12 Even

worse, opioids, including both prescription pain relievers and heroin, were

involved in 28,647 deaths in the United States in 2014 (an average of 78 deaths

per day), more than any year on record. In addition, opioid overdoses

quadrupled between 2000 and 2014.13 In this context, it is obvious that

solutions are needed, but there is disagreement about whether kratom is helping

the problem or contributing to it.

Differing Perceptions of Kratom

At the time of the DEA’s August 31 notice of intent, six US

states (Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, Tennessee, Vermont, and Wisconsin);

Washington, DC; and at least 15 countries, including Thailand, had banned

kratom. It had been included on the DEA’s “Drugs of Concern” list since 2005.1,9

After the notice, there was an outpouring of people who came to the defense of

the plant. Within two weeks, a petition on We the People

(petitions.whitehouse.gov) asking the White House to stop the scheduling had

garnered nearly 125,000 signatures (and, at press time for this article, more

than 143,000 signatures), surpassing the 100,000 necessary to receive a

response.14

In the days leading up to the originally proposed scheduling

date, 51 members of the House of Representatives, spurred by the Botanical

Education Alliance, an organization whose stated mission is to preserve plant

legality through education, formally requested that the DEA delay the

scheduling.15 Shortly thereafter, Senator Orrin Hatch (R–UT), the most senior

Republican senator, wrote a letter asking the DEA “to allow both for a public

comment period and sufficient time for the DEA to outline its evidentiary

standards to the Congress regarding the justification for this proposed action.”16

Days later, Senator Cory Booker (D–NJ), Senator Kirsten

Gillibrand (D–NY), and Senator Ron Wyden (D–OR) wrote an emphatic letter to DEA

Acting Commissioner Chuck Rosenberg in which they echoed Hatch’s requests. They

cited the eight-fold increase in US prison populations from the enforcement of “draconian

drug laws,” writing: “We should not, in haste and without adequate opportunity

for comment and analysis, place substances in categories that may be

inconsistent with their medical value and potential for abuse.”17

Anecdotal Evidence

After the DEA notice, many news articles told the stories of

people who claimed to have benefitted from kratom and who would personally be

affected by its placement in Schedule I. For example, one woman from Missouri

named Margo Burton had been taking two teaspoons of an unspecified preparation

of kratom every three hours to help her cope with pain caused by endometriosis,

a condition in which uterine tissue grows outside the uterus. “I need it so I’m

not hurting, so I can be a good mother,” Burton is quoted as saying. When she

heard about the DEA’s plan to ban kratom, she sobbed.18

Susan Ash, founder of the American Kratom Association (AKA),

a nonprofit that supports kratom users, started using kratom to manage pain

caused by Lyme disease that went undiagnosed for years. In 2008, her condition

became debilitating. “The pain was excruciating,” Ash is quoted as saying. “It

was in my joints. It would wake me up in the middle of the night. It would have

me in the emergency room.” Her doctors began prescribing drugs to treat the

symptoms of the undiagnosed disease, and then began prescribing more drugs to

treat the side effects of the other drugs.18,19

Ash was prescribed a cocktail of as many as 10 different

prescription drugs and soon began suffering serious neurological effects. She

was finally diagnosed with Lyme disease, but, by that point, she was addicted

to painkillers. In 2011, she entered treatment and successfully detoxed, but

she still felt chained to opioids.19 “Life couldn’t have been much worse at

that point. I was not leaving the house at all. I was only leaving the house to

see doctors,” she said. Then, someone suggested that she try kratom and,

although she was skeptical at first, she eventually did. “In a matter of two

weeks, I had the energy, I had the pain relief, and I had the depression and

anxiety relief I needed to become a productive member of society again. It was

such a stark difference and such an immediate change in my life.”19

In a video on YouTube, a US Army veteran, who says he

suffered from terrible foot and lower back pain and migraine headaches, talks

about his experience with kratom and his opinion of the DEA’s proposed

scheduling. “One of my best friends introduced me to this substance called

kratom,” he said. “I started taking it, and my pain went away…. I brew up some

tea leaves, let it steep for 40 minutes or whatnot, have a cup of tea, I feel

better.” Later in the video, he continued: “I’m not talking about snorting

cocaine, shooting up heroin. I’m not even talking about puffing a joint. I’m

talking about brewing some tea, having a sip, and feeling better — being able

to go for a run because my feet don’t kill me after six years in the army.”20

These are just some of the many anecdotal reports about the

potential benefits of kratom. There are hundreds of testimonials on YouTube and

elsewhere, some from military veterans using kratom to cope with post-traumatic

stress disorder (PTSD), some from people using it to manage fibromyalgia and

other painful conditions, and some from people using it to recover from

alcoholism.21 Testimonials like these and responses from members of Congress

played a part in convincing the DEA to withdraw its original notice of intent

and allow for public comment.

A Public Health Threat?

Still, some contend that kratom is dangerous. Dan Fabricant,

PhD, CEO and executive director of the Natural Products Association (NPA), was

the director of the Office of Dietary Supplement Programs at the FDA when the

administration first took actions against kratom as an unapproved new dietary

ingredient. In a recent NPA press release, he noted: “Kratom has been a public

health target for almost five years, and its surging growth in use and

availability is an unfortunate but real example of the federal government’s

unwillingness to use existing authorities to enforce the law. This [the DEA’s

scheduling] is a necessary and welcome step, but unless it is followed with

real enforcement and penalties for those who are selling it in coffee bars, on

the internet, and elsewhere, it will be toothless. Kratom is not an herbal

supplement: it is addictive, harmful, and worse, it may be contributing to [the

US's opioid] epidemic.”22

The original DEA notice stated that there have been numerous

deaths associated with kratom, beginning with a cluster of nine deaths in

Sweden between 2009 and 2010 that were linked to a product called “Krypton.”1

According to other sources, kratom-containing products sold under the name “Krypton”

were found to be adulterated with caffeine and synthetic O-desmethyltramadol (a

metabolite of the prescription opioid tramadol), but the DEA notice does not

mention this adulteration.6,9

According to the DEA notice, five other deaths related to

kratom exposure were subsequently reported in the scientific literature, and

autopsy/medical examiner reports for an additional sixteen deaths confirmed the

presence of MG and 7-OH-MG in biological samples. Of these 21 deaths, 15

occurred between 2014 and 2016.1

A toxicologist was hired by the AKA to review the 15 deaths

that occurred between 2014 and 2016, and in each case the toxicologist disputed

the notion that kratom toxicity was the cause of death.23 According to Ash,

many of these deaths involved other drugs, and some likely involved

pre-existing health conditions.

Adverse interactions have been reported involving kratom tea

taken with substances such as carisoprodol (a muscle relaxant), modafinil (a

wakefulness-promoting agent), propylhexedrine (a stimulant used as a nasal

decongestant), or jimson weed (Datura stramonium, Solanaceae; a tropane

alkaloid-containing plant with hallucinogenic and analgesic properties). In

addition, a fatal case in the United States (presumably counted among the

fatalities noted by the DEA) involved a mixture of kratom, fentanyl (a powerful

synthetic opioid analgesic), diphenhydramine (a sedating antihistamine), caffeine,

and morphine, which was mislabeled and illegally sold as an herbal product.6

Morphine-like Effects

MG and 7-OH-MG produce analgesic effects similar to those of

morphine, the prototypical opioid, and the DEA notice and other sources

classify them as opioids because of their binding affinity for the opioid

receptors.1

The term “opioid” combines “opium” with the suffix “-oid,” which

means “like” or “resembling” and often implies an incomplete or imperfect

resemblance to the preceding element. The term was originally proposed to

describe drugs that have actions similar to, but chemical structures different

from, morphine.24 The term “opioid” should also be distinguished from “opiate,”

which is a narrower term that refers to naturally occurring alkaloids found in

the opium poppy (Papaver somniferum, Papaveraceae), including morphine and

codeine.25

According to the book Kratom and Other Mitragynines (CRC

Press, 2015), substances are typically classified as opioids based on the

following criteria: binding affinity for one or more of the major subtypes of

opioid receptor, morphine-like in vivo effects (such as pain relief), miosis

(excessive constriction of the pupil), constipation, respiratory depression,

tolerance, cross-tolerance to a known opioid, development of dependence, and

similarity of chemical structure to morphine or another opioid.9 It has been

shown that MG and 7-OH-MG meet most of these criteria, at least to some degree.

However, David Kroll, PhD, a pharmacologist, member of the

American Botanical Council’s (ABC’s) Advisory Board, and medical writer who has

written articles about kratom for Scientific American and Forbes.com, said that

the pharmacological actions of MG and 7-OH-MG (see “In Depth: Botany and

Pharmacology of Kratom” section) more closely resemble those of buprenorphine

(a semisynthetic opioid with mixed opioid partial agonist/antagonist effects

and that is used to treat opioid addiction) than those of other, more common

opioids, such as morphine, hydrocodone, oxycodone, and heroin (email, October

16, 2016).

Kratom is one of a finite number of plants that have been

found to produce compounds that have an affinity for opioid receptors,

including P. somniferum; P. bracteatum, which produces thebaine, an opiate

precursor to a variety of semisynthetic opioids, such as buprenorphine26; P.

orientale, which also produces thebaine, in addition to oripavine, another

opiate precursor to several semisynthetic opioids27; Salvia divinorum (Lamiaceae),

which produces salvinorin A9; and Dalea purpurea (Fabaceae), which produces

pawhuskin A, B, and C.28

Respiratory Depression

Perhaps the most significant way in which MG and 7-OH-MG

differ from common opioids is that they have a much lower risk of producing

respiratory depression.21 (Notably, the misuse of the opioids fentanyl and

carfentanil, a fentanyl analog that is approximately 10,000 times more potent

than morphine, has resulted in an epidemic of overdose deaths caused by these

respiration-depressing effects.29) At lower doses, common opioids reduce the

amount of air passing into and out of the lungs in each respiratory cycle, and

therefore depress respiration. At higher doses, opioids further decrease

respiratory rate and impair respiratory rhythm. Opioid use also is associated

with rigidity of the muscles used during respiration and decreased activity of

these muscles during sleep.9 This respiratory depression can starve the brain

of oxygen and lead to permanent brain damage or death. The risk is heightened

when opioids are taken with other depressants, such as alcohol, antihistamines,

barbiturates, benzodiazepines, or general anesthetics.30

“It turns out mitragynine has a very low risk of respiratory

depression,” Kroll is quoted as saying. “It also appears that it’s very

difficult to at least get animals — get mice addicted to ‘mitra,’ either with

the herb or with the pure chemical.”21 In addition, at higher doses, kratom

induces vomiting, reportedly making it difficult to overdose.23

Kratom Use and Potential for Misuse

According to the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and

Drug Addiction (EMCDDA), a few grams of dried kratom leaves produce

invigorating and euphoric effects within about 10 minutes, and these effects

last for about one to one-and-a-half hours. Kratom users report increased

alertness, sociability, and sometimes increased libido. Slight constriction of

the pupils and blushing may occur. In one of the few human clinical

experiments, a 50-mg oral dose of MG produced motor excitement, then giddiness,

loss of motor coordination, and tremors of the extremities and face.6

Larger doses of dried kratom leaves (10-25 g) may initially

cause sweating, dizziness, nausea, and dysphoria, but these effects are quickly

replaced with euphoria, calmness, and a dreamlike state that can last for up to

six hours. Miosis also occurs.6

Traditionally, when kratom is consumed as a tea, lemon juice

is often added to encourage extraction of the alkaloids in the plant. Sugar or

honey may be added to mask the bitterness of the tea. The dried leaves are also

sometimes smoked. The veins of the leaves are usually removed before

consumption, and salt may be added to prevent constipation. Kratom consumption

is sometimes followed by drinking warm water, coffee, tea, or palm sugar syrup.6

“With anything, there are dangers of using too much,” Walter

C. Prozialeck, PhD, professor of pharmacology at Midwestern University and

co-author of a review of the pharmacology of kratom, is quoted as saying.19 “But

the amount that a person has to take in to get any severe effects is ridiculously

high. You’re talking 10 to 15 grams of raw leaf. Most people who are using

kratom for pain management don’t take that much. Most people can’t take that

much.”

In addition, according to Prozialeck, kratom doesn’t produce

much of a psychoactive high in low to moderate doses. “After researching the

literature, I found that there were more positive aspects to kratom than there

were negative,” he is quoted as saying. “Additional studies are needed to

explore potential benefits of kratom. Also, work is needed to look at toxicity,

though.”19

The original DEA notice pointed to data from poison control

centers in the United States as evidence “that there is an increase in the

number of individuals abusing kratom.” Between 2000 and 2005, the American

Association of Poison Control Centers identified two exposures to kratom. In

the six-year period from January 2010 through December 2015, US poison centers

received 660 calls related to kratom exposure, and 428 (64.8%) of those

involved kratom being used with other substances, including ethanol,

benzodiazepines, narcotics, acetaminophen, and other botanicals.1 Compared to

the more than 3.1 million calls received by the US’s 55 poison centers in 2013

alone, calls involving kratom accounted for a tiny fraction.31

In addition, the DEA notice stated that it is especially

concerning that “users have turned to kratom as a replacement for other

opioids, such as heroin.”1 This is despite the fact that heroin was involved in

more than 8,200 deaths in the United States in 2013, and the fact that heroin

injection increases the risk of serious viral infections, including HIV and

hepatitis B and C, and bacterial infections of the skin, bloodstream, and

heart.32 Furthermore, methadone, a synthetic opioid that is sometimes used to

help wean recovering addicts off heroin, is involved in nearly 5,000 overdose

deaths per year.33 According to Kroll, buprenorphine (the pharmacological

actions of which, again, resemble those of MG and 7-OH-MG) has been replacing

methadone in opioid maintenance therapy for recovering opioid addicts. There is

concern among kratom proponents that if the DEA criminalizes kratom, it will

push some people back to abusing heroin and/or other opioids.23 Perhaps time

will tell.

Evidence suggests that kratom can be at least somewhat

addictive. Mark Swogger, PhD, an assistant professor of psychiatry at the

University of Rochester Medical Center and co-author of a qualitative analysis

of 161 firsthand descriptions of human kratom use, is quoted as saying: “I

think it’s pretty safe to say that kratom has at least some addiction

potential. The data is fairly strong on that, and our study also found that

people are reporting addiction. Overall, we found that it’s really mild

compared to [common] opioid addiction and it didn’t seem to last as long.”34

In addition, tolerance has been observed. New kratom users

typically need only a few leaves to feel an impact, but heavy users may need to

chew the leaves between three and 10 times per day, and some users find that,

over time, they need to increase the number of leaves chewed to between 10 and

30, or more, per day.9 Furthermore, mice treated with 7-OH-MG developed

tolerance, cross-tolerance to morphine, and withdrawal symptoms that could be

brought on by administration of naloxone, a semisynthetic opioid receptor

antagonist (i.e., an inhibitor of receptor activity) that is used to reverse

the effects of opioids in cases of overdose or postoperative sedation.6

Regular kratom users may also become dependent. Human

withdrawal symptoms are fairly mild and usually subside within a week. These

symptoms include anxiety, restlessness, runny nose, muscle pain, weakness,

lethargy, nausea, sweating, craving, jerky movements of the limbs, sleep

disturbances, and sometimes hallucination.6

Prior Regulatory Actions

Before the DEA’s notice of intent, kratom qualified as a

dietary ingredient under the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FDCA) of

1938 that could be used in dietary supplement products. However, under the

Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act (DSHEA) of 1994, the FDA considers

it a new dietary ingredient (NDI) because there is no information demonstrating

that it was marketed as a dietary ingredient in the United States before

October 15, 1994. If an ingredient is considered “new,” then companies must

meet certain additional regulatory requirements before using the ingredient in

a supplement product.

The FDA did not believe that these regulatory requirements

had been satisfied by any company that was marketing and selling kratom, and

thus considered kratom and kratom-containing dietary supplements and bulk

dietary ingredients to be adulterated under the FDCA. In February 2014, the FDA

issued an import alert notifying field personnel that they could detain

kratom-containing products listed in the alert without physical inspection.35

In a separate alert, the FDA announced that other listed kratom products could

be detained without physical inspection because these products were considered

unapproved and/or misbranded drugs.36 In these cases, importers and marketers

were making unauthorized disease-treatment claims for their products. Between

2014 and the time of the DEA notice, products from 121 firms had been added to

the two FDA import alerts.1

In September 2014, US Marshals, at the request of the FDA,

seized more than 25,000 pounds of raw kratom material worth more than $5

million.37 In January 2016, US Marshals, again at the request of the FDA,

seized nearly 90,000 bottles of dietary supplements labeled as containing kratom.38

And again, in August 2016, US Marshals, at the request of the FDA, seized 100

cases of products labeled as containing kratom.39

Between February 2014 and July 2016, more than 55,000

kilograms (121,254 pounds) of kratom material was encountered at various ports

of entry in the United States. In addition, at the time of the DEA notice, more

than 57,000 kilograms (125,663 pounds) of kratom material offered for import at

numerous ports of entry between 2014 and 2016 was awaiting an admissibility

decision by the FDA. At the time of the DEA notice, the amount of kratom that

had been seized or that was awaiting an admissibility decision was estimated to

be enough to produce more than 12 million doses of kratom. According to the

DEA, “such alarming quantities create an imminent public health and safety

threat.”1

The DEA’s scheduling proposal came as a surprise to some. “While

I’m not surprised that the FDA began to seize kratom as an unapproved drug…, I

was surprised by the DEA’s intent to place two of the alkaloids in Schedule I,”

Kroll wrote (email, September 19, 2016). “But I have to admit that it took me

writing an article about kratom and getting reader comments before I realized

people were overwhelmingly using the herb medically and not as a recreational psychotropic.”

Impact on Research

Kroll also mentioned that two important kratom studies were

only recently published: one by Kruegel et al. (from Columbia University) that

was published in May 2016 in the Journal of the American Chemical Society40 and

one by Váradi et al. (from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center) that was

published in August 2016 in the Journal of Medicinal Chemistry.41 “So the DEA

may not have been aware of the firm distinctions between Mitragyna speciosa

alkaloids and strong, full agonist opioids [a full agonist binds to and

activates a receptor, producing full activity at that receptor],” Kroll wrote. “What

this tells me is that the DEA rushed to judgment based on the weak adverse

[event] report record of the herb and/or its adulterants without fully

investigating that its compounds were pharmacologically distinct from strong

opioid agonists [e.g., morphine].”

Ash of the AKA is quoted as saying she “really believed that

because of the progress medical marijuana has made through the states that the

federal government was going to leave kratom alone and leave it to the states

to decide whether it was appropriate to be legal.”42

It is not entirely clear how the scheduling would impact

research on kratom. Researchers will have to apply to the DEA for a Schedule I

research license, which requires a fairly stringent collection of documentation

and security protocols that can take time to implement, up to a year or more,

wrote Kroll. “The researchers I’ve spoken to are more concerned about the

availability of research amounts of raw plant material, since import

restrictions on Schedule I substances are quite ornery,” he wrote.

DEA spokesperson Russ Baer is quoted as saying, “As is the

case with any controlled substance, the DEA will implement aggregate production

quotas for kratom and make available an adequate and uninterrupted supply of

research-grade material to accommodate valid scientists and researchers.”43

It is possible this may be done through a federal supply

contract similar to the marijuana farm at the University of Mississippi, which,

until recently, supplied all of the medical cannabis used for DEA-approved

research.44

According to Jahan Marcu, PhD, chief scientific officer for

Americans for Safe Access, a medical cannabis advocacy organization, “it is

unclear how long it would take the DEA to supply kratom, since it can take 20

years for a tree to reach maturity. A federal supply of kratom, produced in the

US, is 20 years away, leaving our [kratom] researchers to whither on the vine

because they do not have access to their research tools” (email, October 13,

2016).

Schedule I study restrictions on kratom would undoubtedly “stall

the scientific study of the herb at a time when our understanding of its molecular

pharmacology has never been more advanced and promising,” Kroll wrote.

Additionally, he thinks the scheduling will hinder the study of semisynthetic

analogs of the M. speciosa alkaloids that could lead to new FDA-approved drugs

for pain and/or recovery from opioid and alcohol dependence.

In Depth: Botany and Pharmacology of Kratom

Kratom grows in swamps and damp valley areas that are rich

with humus, and forms “dense stands in the new alluvial substrate of ox-bow

lakes and low muddy river banks that are frequently inundated.”9 The species is

said to be a common riverside pioneer (i.e., a species that is the first to

colonize previously disrupted or damaged ecosystems).

According to one source, the tree can grow to 4-16 meters

(13-52 feet) tall with a spread of more than 15 feet.6,45 According to Kratom

and Other Mitragynines, it can grow to 25 meters (82 feet) in height and two to

three feet in diameter. The trunk is usually straight. The outer bark is smooth

and gray, and the inner bark is pinkish.9 The leaves are oval or

ovate-lanceolate and dark green.6 They are 14-20 centimeters long and 7-12

centimeters wide.9 The veins of the leaves are either greenish-white or red.

Leaves with greenish-white veins are said to be more potent. The average weight

of a fresh leaf is about 1.7 grams, while the average weight of a dried leaf is

about 0.43 grams. The tree produces yellow and globular flowers that can bear

up to 120 florets. The fruit is a capsule that contains several small, flat

seeds.6

Alkaloid Chemistry and Composition

The tree contains more than 40 structurally related

alkaloids, in addition to several flavonoids, saponins, polyphenols, and

glycosides. Kratom is the only species known to produce the indole alkaloids MG

and 7-OH-MG, two of the main psychoactive components in the plant.6 At least

three other alkaloids found in kratom (speciogynine, paynantheine, and

speciociliatine) have been shown to have some opioid receptor affinity.46

The chemical profile of kratom varies depending on several

factors: the variety and age of the plant, the environment, and the time of

harvest. The total alkaloid concentration in dried leaves typically ranges from

0.5% to 1.5%.6

MG is structurally similar to yohimbine (a compound derived

from the African tree yohimbe [Pausinystalia johimbe, Rubiaceae]),10 and it is

typically the most abundant alkaloid in the leaves,9 although it has also

reportedly been found in the fruits and stembark of kratom.47 MG was first

isolated in 1921, and its structure was determined in 1965.9

The amount of MG that kratom yields depends on geography and

the maturity of the leaves.9 For example, MG accounted for 66% of the crude

base of alkaloids extracted from young leaves of a specimen from Thailand,

while the compound accounted for only 12% of the alkaloids extracted from

mature leaves of a specimen from Malaysia.47 It is possible that, in this case,

geography, not leaf maturity, accounted for the difference, since, according to

Kratom and Other Mitragynines, MG is typically much more abundant in older

plants than younger ones, and much more abundant in Thai plants than Malaysian

ones. Interestingly, the predominant alkaloid found in a kratom specimen grown

at the University of Mississippi was the oxindole-type mitraphylline (at 45% of

the total alkaloids), not MG.9 Mitraphylline is also found in the bark of cat’s

claw (Uncaria tomentosa, Rubiaceae).48

7-OH-MG is a minor alkaloidal constituent of kratom. It

accounted for just 2% of the crude base of alkaloids extracted from young

leaves of a specimen from Thailand. A 2004 study using guinea pigs showed that

7-OH-MG was almost 50-fold more potent than MG and more than 10-fold more

potent than morphine.47 Another study using guinea pigs, however, showed that

7-OH-MG was 30-fold more potent than MG and 17-fold more potent than morphine.46

It is thought that 7-OH-MG is more potent than morphine because it is more

lipophilic (i.e., able to combine with or dissolve in fats) than morphine and

distributes more quickly across the blood-brain barrier, a diffusion barrier

that impedes the influx of most compounds from the blood into the brain.9,49

However, 7-OH-MG is less lipophilic than MG, and it is thought that it is more

potent than MG because of tighter receptor binding to the mu-opioid receptors

(MORs), which is associated with 7-OH-MG’s hydroxyl group (-OH) at the C7

position, a structural feature not present in MG.9,40

MG and mitraphylline have also been shown to be able

to diffuse across the blood-brain barrier in vitro. In addition, MG and 7-OH-MG

were found by one study to be unstable in simulated gastric fluid (which could

account for why some of the 7-OH-MG [23%] was converted to MG), but both were

found to be stable in simulated intestinal fluid.48 MG is not soluble in water,

but it is soluble in conventional organic solvents (i.e., solvents that contain

carbon atoms).6

Receptor Activity and Mechanisms of Action

According to the study conducted by researchers at Columbia

University, both MG and 7-OH-MG are partial agonists of the MORs, and MG was

shown to have about 34% of the maximal effect of a full agonist. This study was

conducted using human kidney cells that had been genetically modified to

express the human versions of each opioid receptor subtype. MORs are located in

the brain, spinal cord, and gastrointestinal tract, and MOR agonists (like

morphine) are the “gold standard” of pain therapy. But, in addition to

producing analgesia, MOR activation can produce serious adverse side effects,

including constipation, sedation, nausea, itching, and, as previously

mentioned, respiratory depression. In addition, the euphoria produced by MOR

agonists makes them widely subject to misuse.40

Kroll proposed three explanations for why MG and 7-OH-MG

cause less-to-no respiratory depression, compared with other MOR agonists. “First,

they are partial agonists at the MORs, meaning that the maximal effect is lower

than the maximal effect of a full agonist like morphine,” he wrote. “What this

means is that no matter how much MG or 7-OH-MG you put in the system, you’ll

never get to the same effect as the maximum effect of morphine.”

“Second, the Mitragyna speciosa alkaloids all appear to be ‘biased’

toward the G-protein signaling pathway and away from the beta-arrestin-2

pathway,” Kroll continued. “This is a relatively new and often confusing

concept, even to some pharmacologists. When a receptor sitting on the cell

surface is bound by a drug, it can either do nothing (as with a blocker, or

antagonist), or it can transduce a signal to the inside of the cell that

triggers a cascade of events. MORs can signal through a so-called G-protein

and/or the beta-arrestin-2 protein. Beta-arrestin-2 seems, at least in part, to

mediate respiratory depression (as well as tolerance, accounting for why

patients and addicts all require progressively more opioids over time to

produce the same effect).”

According to Kroll, a possible third reason “is that MG and

7-OH-MG are both antagonists at kappa-opioid receptors [KORs], albeit with less

potency than as partial MOR agonists. The overall effect is that you can get

painkilling approaching that of morphine with much less respiratory depression.”

KOR antagonists, such as MG and 7-OH-MG, have shown the

potential to help promote stress resilience, which may help treat certain types

of anxiety, depression, and addiction disorders, all of which are exacerbated

by hypersensitivity to stress.50 The Columbia University study also showed that

MG and 7-OH-MG are antagonists of the delta-opioid receptors (DORs).40 Animal

studies suggest that DORs control rewarding or addictive properties of drugs

that act on the MORs or other non-opioid receptor sites. Therefore, DOR

antagonists may have the ability to block morphine reward and tolerance.51

Interestingly, the Thai strain of kratom used by the

Columbia University researchers yielded only trace quantities of 7-OH-MG that

were too small to isolate. “Therefore,” the researchers wrote, “it is doubtful

that this alkaloid is a universal constituent of all Mitragyna speciosa preparations

and is unlikely to generally account for the psychoactive properties of this

plant.” They were, however, able to prepare 7-OH-MG through photochemical

oxidation of MG, which, according to Kroll, indicates that “growing and storage

conditions may dramatically affect the overall potency of the botanical

material.”40

In addition, the study found that paynantheine,

speciogynine, and speciociliatine (which, together, accounted for a percentage

of the total extracted alkaloids that was approximately equal to the percentage

accounted for by MG) all exhibited antagonist activity at the MORs that competed

with the agonist activity of MG. The researchers, therefore, concluded that “the

gross psychoactive effects of crude plant material are likely to represent a

complex interplay of competing agonist and antagonist effects at the opioid

receptors.”40

Kratom’s unusual and paradoxical stimulant/sedative effects

are not fully understood. “Some opioids have a paradoxical stimulating effect

in some patients, particularly in elderly folks,” Kroll wrote. “But the Mitragyna

speciosa alkaloids have some other receptor effects (e.g., alpha-2-adrenergic)

that may or may not be relevant for the amounts of kratom people consume. From

anecdotes, the [stimulating] effect does sound like it’s real but it hasn’t

been systematically studied in humans or attributed to a specific compound or

neuroreceptor system.”

One guinea pig study showed that MG may produce analgesic

effects through the blockade of neuronal calcium ion (Ca2+) channels.52 And

another source suggests that MG’s analgesic effects may involve the activation of

serotonergic and noradrenergic pathways that descend down the spinal cord. In

addition, kratom seems to have anti-inflammatory properties.10

Conclusion

Kratom is a complicated plant that is not fully understood,

either by the scientific community or by the global community. It is likely

that language has played a part in shaping perceptions about kratom, with some

sources referring to it as an opium “substitute” and other sources referring to

it as an opium “remedy.”9 Different perceptions of the plant have led some to

celebrate it for its medicinal potential and others to malign it for its abuse

potential.

At a time when the United States needs safer alternatives to

opioids more than ever, the DEA’s placement of the kratom alkaloids in Schedule

I would force those who were successfully using the plant for pain management,

opioid withdrawal, and other therapeutic purposes to become criminals, seek

alternatives that may be more dangerous, or simply do without. Detractors point

to the fact that kratom users may become addicted to, dependent on, and

tolerant of kratom over time. Proponents emphasize that the kratom alkaloids

produce less constipation and, more importantly, less-to-no respiratory

depression, compared to other common opioids.

However, proponents, and even some detractors, agree that

more research is needed, on both the potential benefits and the potential

dangers of kratom. DEA scheduling would make this research more difficult.

“I think that the best kratom researchers should get

together and write a couple of clinical trial protocols to the National Center

for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) to investigate a

well-characterized, analytical and GMP[good manufacturing practice]-verified

kratom product to investigate pharmacokinetics of each compound and metabolite,

and efficacy in pain and substance dependence recovery, while also assessing

adverse effects, including dependence on the kratom itself,” Kroll wrote.

As far as the individual compounds, Kroll believes that MG,

7-OH-MG, the fermentation product mitragynine pseudoindoxyl, and semisynthetic

analogs of each should be investigated as single-entity drugs. “But the

semisynthetic analogs will likely be required, not just for intellectual

property purposes, but for improved half-life and dosage formulation,” Kroll

wrote. “Users have told me they need to dose with kratom tea up to four or five

times in a day, and there is some published data that MG’s half-life [i.e., the

time it takes for half of the administered amount to be eliminated from the

bloodstream] is on the order of an hour.”

Though according to some it is not legally realistic to

expect kratom to remain unregulated, there is interest within the scientific

community about the potential for new therapeutics derived from the plant

(either single compounds or whole-plant preparations) to become safer and

better pain-relievers and opioid recovery aids. “At a time when the opioid

dependence issue is at its greatest national awareness,” Kroll wrote, “I think

we need any tool — pharmacological, psychological, [mindful] meditation, yoga,

etc. — that can relieve people of the burden, pain, and potential lethality of

substance dependence.”

Sidebar: Nomenclature and Taxonomy of Kratom

Mitragyna is a small genus that, depending on the taxonomic

treatment, includes seven to 10 species. (A taxonomic treatment is a

publication, or a section of a publication, that documents the features and/or

distributions of a related group of organisms [i.e., a taxon] in ways that

adhere to highly formalized conventions.54) According to one treatment, four Mitragyna

species are found in Africa, while six are found in South and Southeast Asia.

The Asian species are distributed between India and New Guinea.9

The Dutch botanist Pieter Willem Korthals (1807-1892) first

described the genus. As a member of the Commission for Natural Sciences of the

Dutch East India Company from 1830 to 1837, Korthals made important botanical

discoveries and collections in the Malay Archipelago.9 He named the genus Mitragyna

because he thought the leaves and stigmas of the flowers of one of the

specimens he observed resembled the shape of a bishop’s mitre.6 In 1839,

Korthals published the genus and the species name M. speciosa in the same

publication, but he didn’t include a botanical description of M. speciosa, and

that name is therefore considered a nomen nudum (a “naked name”). In 1842,

Korthals transferred the species to the genus Stephegyne. Various authors

subsequently renamed the species Nauclea korthalsii, then Nauclea luzoniensis,

then Nauclea speciosa, before British naturalist George Haviland set the

current accepted species name as M. speciosa in 1897.9

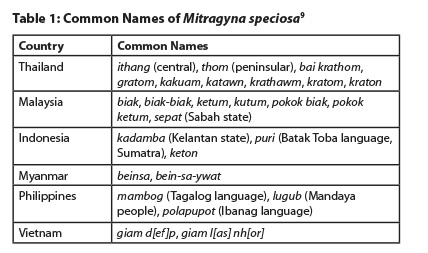

The common name “kratom” originates from Thailand,9 but the

plant has many common names (see Table 1). According to one source, “kratom” is

likely derived from the Sanskrit kadam, a name that refers to Neolamarckia

cadamba (Rubiaceae), a widespread tree that is sacred in Hinduism. Similar

names are used for various related tree species in the region.9

Sidebar: Kratom in Thailand

Perhaps nowhere in the world does kratom have a longer and

more interesting history than in Thailand. As in some other Southeast Asian countries,

there are potentially toxic, kratom-containing admixtures used in Thailand, and

various socioeconomic and political factors contribute to the perception of

kratom misuse. Some of these factors may have some relevance to the current

kratom debate in the United States.

In Thailand, chewing kratom leaves is a tradition that has

been practiced for centuries, especially on the southern peninsula where the

tree is more commonly found. According to one source, “In southern Thailand,

traditional kratom use is not perceived as ‘drug use’ and does not lead to

stigmatization or discrimination of users. Kratom is generally part of a way of

life in the south, closely embedded in traditions and customs such as local

ceremonies, traditional cultural performances, and teashops, as well as in

agricultural and manual labor in the context of rubber plantations and

seafaring.”53

In some districts in southern Thailand, as much as 70% of

the male population uses kratom on a daily basis (as of 2011), and many people

consider it similar to drinking coffee. Some southern provinces, especially

Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat, are predominantly made up of Muslims who,

because of the dictates of Islam, cannot consume alcohol. Kratom is an

alternative that is not prohibited by the clergy, but it is controlled by the

government.53

Kratom was banned in Thailand under the Kratom Act of 1943.

Leading up to the ban, the Thai government had started levying taxes on opium

users and retailers. Because opium started becoming more expensive, many users

switched to kratom to help manage opium withdrawal. With the launch of the

Pacific War (which debatably began in December 1941 when Japan invaded Thailand

and attacked British possessions in the Pacific) and decreasing opium revenues,

the Thai government took action to eliminate competition in the opium trade.53

In 1943, a government official was quoted as saying: “Taxes

for opium are high while kratom is currently not being taxed. With the increase

of those taxes, people are starting to use kratom instead and this has had a

visible impact on our government’s income.”53

After World War II, the Kratom Act was not aggressively

enforced, and kratom could be grown in moderation and consumed openly. In 1979,

kratom was included in the least restrictive and punitive schedule of the Thai

Narcotics Act. In the early 2000s, coinciding with a crackdown on illegal drugs

that was initiated by the Thai government, the number of seizures and arrests

related to kratom increased greatly. Shortly thereafter, in the mid-2000s, a

kratom-containing cocktail called “4x100” started being used by some young

people.53 The cocktail involves boiling kratom leaves (15 to 100 at a time) to

produce a tea, which is mixed with codeine- or diphenhydramine-containing cough

syrup, a soft drink (usually Coca-Cola), and ice cubes.9,53 Typically, the

cocktail is prepared twice or more per day, depending on the availability and

cost of the ingredients. 4x100 users are typically subject to some community

discrimination, though not as much as yaba (methamphetamine) or heroin users.53

There have been concerns about reports of the cocktail being

laced with additives “such as benzodiazepines, powder from fluorescent tubes,

powdered mosquito coils, road paint, pesticides, ashes from dead bodies, and

other substances found in the local environment to ‘enhance’ the effect of the

cocktail.” Apparently, little evidence to substantiate these claims has been

found, and some contend these are exaggerations meant to vilify those who

consume the cocktail, again, typically young people. One 4x100 user was quoted

as saying: “We want to get high, not kill ourselves!”53

Because of these reports, however, authorities, with the

stated intent of protecting young people, have been instructed to eradicate

kratom trees and actively look for kratom and 4x100 users in certain

communities (as of 2011). Beginning in the mid-2000s, several eradication

campaigns in the southern provinces led to large numbers of kratom trees being

cut down, either by law enforcement or by community groups (whether voluntarily

or not). In Pattani, Yala, and Narathiwat provinces, few kratom trees are left

in the wild. Authorities in Satun, Surat Thani, and Trang provinces are more

lenient and tolerate a few trees in the community and up to one tree per

household (as of 2011).53

According to one source, efforts to control kratom between

the early 2000s and 2011 did little good. Kratom is still popular in the

southern provinces and around Bangkok, though not among women (who usually

prefer to chew betel nut [Areca catechu, Arecaceae] instead). The traditional

chewers (as opposed to the 4x100 users) often own the land where kratom grows

and are, therefore, usually the ones targeted by eradication campaigns. Younger

4x100 users sometimes resort to stealing from trees in the community, which has

led some traditional chewers to set up barbed wire and other protection

mechanisms around kratom trees. In addition, efforts to limit 4x100 use has

almost exclusively focused on kratom, instead of trying to control cough syrup

and benzodiazepines, the most potentially harmful components of the cocktail.53

Although kratom is technically illegal in Thailand, law

enforcement has been uneven and many people continue to view kratom as a

traditional medicine. According to some, kratom should be decriminalized, and

community leaders should be empowered to control production and consumption of

kratom. In addition, some argue that concerns surrounding 4x100 use have little

to nothing to do with kratom.53

References

- Schedules of Controlled Substances: Temporary Placement of Mitragynine and 7-Hydroxymitragynine Into Schedule I. The Federal Register. Available at: www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/08/31/2016-20803/schedules-of-controlled-substances-temporary-placement-of-mitragynine-and-7-hydroxymitragynine-into. Accessed September 14, 2016.

- Part 1308.11 Schedule I. Drug Enforcement Administration website. Available at: www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/21cfr/cfr/1308/1308_11.htm. Accessed September 14, 2016.

- Controlled Substances Act. Food and Drug Administration website. Available at: www.fda.gov/regulatoryinformation/legislation/ucm148726.htm. Accessed September 15, 2016.

- Withdrawal of Notice of Intent to Temporarily Place Mitragynine and 7-Hydroxymitragynine Into Schedule I. The Federal Register. Available at: www.federalregister.gov/documents/2016/10/13/2016-24659/withdrawal-of-notice-of-intent-to-temporarily-place-mitragynine-and-7-hydroxymitragynine-into. Accessed October 13, 2016.

- Ingraham C. The DEA is withdrawing a proposal to ban another plant after the internet got really mad. The Washington Post website. October 12, 2016. Available at: www.washingtonpost.com/news/wonk/wp/2016/10/12/the-dea-is-reversing-its-insane-decision-to-ban-the-opiate-like-plant-kratom-for-now. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa) drug profile. European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction website. Available at: www.emcdda.europa.eu/publications/drug-profiles/kratom.

- The Controlled Substances Act (CSA): Overview. FindLaw website. Available at: http://criminal.findlaw.com/criminal-charges/controlled-substances-act-csa-overview.html. Accessed September 15, 2016.

- Part 1308.12 Schedule II. Drug Enforcement Administration website. Available at: www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/21cfr/cfr/1308/1308_12.htm. Accessed September 14, 2016.

- Raffa RB, ed. Kratom and Other Mitragynines: The Chemistry and Pharmacology of Opioids from a Non-Opium Source. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press; 2015.

- Prozialeck WC, Jivan JK, Andurkar. Pharmacology of kratom: An emerging botanical agent with stimulant, analgesic and opioid-like effects. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 2012;112(12):792-799. Available at: http://jaoa.org/article.aspx?articleid=2094342. Accessed September 14, 2016.

- Cinosi E, Martinotti G, Simonato P. Following “the roots” of kratom (Mitragyna speciosa): The evolution of an enhancer from a traditional use to increase work and productivity in Southeast Asia to a recreational psychoactive drug in western countries. Biomed Res Int. 2015;2015:968786. doi: 10.1155/2015/968786.

- Paulozzi LJ, Mack KA, Hockenberry JM. Vital Signs: Variation Among States in Prescribing Opioid Pain Relievers and Benzodiazepines — United States, 2012. CDC website. Available at: www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6326a2.htm. Accessed September 14, 2016.

- Injury Prevention and Control: Opioid Overdose. CDC website. Available at: www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/data/statedeaths.html. Accessed September 14, 2016.

- Please do not make Kratom a Schedule I Substance. White House website.

Available at: http://petitions.whitehouse.gov/petition/please-do-not-make-kratom-schedule-i-substance. Accessed September 30, 2016.

- Ault A. Congress Members Call for Halt on DEA Kratom Ban. Medscape website. September 28, 2016. Available at: www.medscape.com/viewarticle/869402. Accessed September 30, 2016.

- DiSalvo D. Kratom Has the Senate’s Attention, and the DEA’s Schedule I Date May Shift. Forbes website. September 29, 2016. Available at: www.forbes.com/sites/daviddisalvo/2016/09/29/kratom-now-has-the-senates-attention-and-the-deas-schedule-i-date-may-shift. Accessed September 30, 2016.

- Kroll D. DEA Delays Kratom Ban, More Senators Object to Process and “Unintended Consequences.” Forbes website. September 30, 2016. Available at: www.forbes.com/sites/davidkroll/2016/09/30/dea-delays-kratom-ban-more-senators-object-to-process-and-unintended-consequences. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- Boodman E. Hidden Network of Kratom Devotees Tries to Keep the Supplement Safe — and Legal. Stat News website. September 2, 2016. Available at: www.statnews.com/2016/09/02/kratom-devotees-fight-for-supplement/. Accessed September 15, 2016.

- Wing N. Some Say Kratom is a Solution to Opioid Addiction. Not if Drug Warriors Ban It First. Huffington Post website. March 3, 2016. Available at: www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/kratom-ban-drug-policy_us_56c38a87e4b0c3c55052ee3f. Accessed September 19, 2016.

- Soldier of the Year Speaks Out on Soldiers for Change on Kratom. YouTube website. September 2, 2016. Available at: www.youtube.com/watch?v=7VwKcTH2nik. Accessed September 19, 2016.

- Silverman L. Kratom Advocates Speak Out Against Proposed Government Ban. NPR website. September 12, 2016. Available at: www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2016/09/12/493295493/kratom-advocates-speak-out-against-proposed-government-ban. Accessed September 16, 2016.

- DEA Kratom Change “Toothless” Without United States Government Enforcement, Says NPA [press release]. Washington, DC: Natural Products Association; August 31, 2016. Available at: www.npainfo.org/App_Themes/NPA/docs/press/PressReleases/Kratom%20Classification.pdf. Accessed September 19, 2016.

- Nelson S. DEA’s Sudden ‘Herbal Heroin’ Ban Triggers Stiff Resistance from Kratom Community. US News website. September 1, 2016. Available at: www.usnews.com/news/articles/2016-09-01/deas-sudden-herbal-heroin-ban-triggers-stiff-resistance-from-kratom-community. Accessed September 19, 2016.

- Opium and opioids: a brief history. Available at: www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0034-70942005000100015&script=sci_arttext&tlng=en. Accessed September 21, 2016.

- Levine B, ed. Principles of Forensic Toxicology. Washington, DC: AACC Press; 2003.

- Seddigh M, Jolliff GD, Calhoun W, Crane JM. Papaver bracteatum, potential commercial source of codeine. Economic Botany. 1982;36(4):433-441.

- Shafiee A, Lalezari I, Nasseri-Nouri P, Asgharian R. Alkaloids of Papaver orientale and Papaver pseudo-orientale. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 1975;64(9):1570-1572. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600640937.

- Belofsky G, French AN, Wallace DR, Dodson SL. New geranyl stilbenes from Dalea purpurea with in vitro opioid receptor affinity. J Nat Prod. 2004;67(1):26-30.

- Emerging Trends and Alerts. National Institute on Drug Abuse website. Available at: www.drugabuse.gov/drugs-abuse/emerging-trends-alerts. Accessed October 18, 2016.

- What Are the Possible Consequences of Opioid Use and Abuse? Drug Abuse website. Available at: www.drugabuse.gov/publications/research-reports/prescription-drugs/opioids/what-are-possible-consequences-opioid-use-abuse. Accessed September 22, 2016.

- American Association of Poison Control Centers. AAPCC website. Available at: www.aapcc.org/. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Today’s Heroin Epidemic. CDC website. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/heroin/. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Prescription Painkiller Overdoses. CDC website. Available at: www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/methadoneoverdoses/. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Szalavitz M. Why Banning the Controversial Painkiller Kratom Could Be Bad News for America’s Heroin Addicts. Vice website. January 20, 2016. Available at: www.vice.com/read/why-banning-the-controversial-painkiller-kratom-could-be-bad-news-for-americas-heroin-addicts. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Import Alert 54-15. Food and Drug Administration website. Available at: www.accessdata.fda.gov/cms_ia/importalert_190.html. Accessed September 28, 2016.

- US Marshals seize botanical substances kratom from southern California facility [press release]. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration; September 25, 2014. Available at: www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm416318.htm. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- US Marshals seize dietary supplements containing kratom [press release]. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration; January 6, 2016. Available at: www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm480344.htm. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Kratom seized in California by US Marshals Service [press release]. Silver Spring, MD: Food and Drug Administration; August 4, 2016. Available at: www.fda.gov/NewsEvents/Newsroom/PressAnnouncements/ucm515085.htm. Accessed September 26, 2016.

- Kruegel AC, Gassaway MM, Kapoor A, et al. Synthetic and receptor signaling explorations of the Mitragyna alkaloids: Mitragynine as an atypical molecular framework for opioid receptor modulators. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138(21):6754-64. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b00360.

- Varadi A, Marrone GF, Palmer TC, et al. Mitragynine/corynantheidine pseudoindoxyls as opioid analgesics with mu agonism and delta antagonism, which do not recruit beta-arrestin-2. J Med Chem. 2016;59(18):8381-8397. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00748.

- Wing N. Feds Declare War on Herb Touted as a Solution to Opioid Addiction. Huffington Post website. August 30, 2016. Available at: www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/dea-kratom-schedule-i_us_57c5c263e4b0cdfc5ac98b83. Accessed September 21, 2016.

- Boodman E. Kratom Ban Will Hinder Studies of the Plant for Treating Pain or Addiction, Researchers Say. Stat News website. September 8, 2016. Available at: www.statnews.com/2016/09/08/kratom-ban-hinders-research/. Accessed September 28, 2016.

- Halper E. DEA Ends Its Monopoly on Marijuana Growing for Medical Research. Los Angeles Times. August 11, 2016. Available at: www.latimes.com/politics/la-na-marijuana-dea-20160811-snap-story.html. Accessed September 28, 2016.

- Kratom (Mitragyna speciosa Korth). Drug Enforcement Administration website. Available at: www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drug_chem_info/kratom.pdf. Accessed September 28, 2016.

- Horie S, Koyama F, Takayama H, et al. Indole alkaloids of a Thai medicinal herb, Mitragyna speciosa, that has opioid agonistic effect in guinea pig ileum. Planta Medica. 2005;71(3):231-236. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-837822.

- Takayama H. Chemistry and pharmacology of analgesic indole alkaloids from the Rubiaceous plant, Mitragyna speciosa. Chem Pharm Bull. 2004;52(8):916-928.

- Manda VK, Avula B, Ali Z, Khan IA, Walker LA, Khan SI. Evaluation of in vitro absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) properties of mitragynine, 7-hydroxymitragynine, and mitraphylline. Planta Medica. 2014;80(7):568-576. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1368444.

- Ballabh P, Braun A, Nedergaard M. The blood-brain barrier: an overview: structure, regulation, and clinical implications. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;16(1):1-13.

- Chavkin C. The therapeutic potential of κ-opioids for treatment of pain and addiction. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2011;36:369-370. doi:10.1038/npp.2010.137.

- Pradhan AA, Befort K, Nozaki C, Gaveriaux-Ruff C, Kieffer BL. The delta opioid receptor: an evolving target for the treatment of brain disorders. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32(10):581-590. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.06.008.

- Matsumoto K, Yamamoto LT, Watanabe K, et al. Inhibitory effect of mitragynine, an analgesic alkaloid from Thai herbal medicine, on neurogenic contraction of the vas deferens. Life Sciences. 2005;78(2):187-194.

- Tanguay P. Kratom in Thailand: Decriminalization and Community Control? Transnational Institute website. Available at: www.tni.org/files/download/kratom-briefing-dlr13.pdf. Accessed October 3, 2016.

- Agosti D. What is a treatment? Biosyscontext website. Available at: http://biosyscontext.blogspot.com/2011/02/what-is-treatment-on-way-to-define-or.html. Accessed October 6, 2016.

|