Issue: 34 Page: 22

MA HUANG: ANCIENT HERB, MODERN MEDICINE, REGULATORY DILEMMA; A REVIEW OF THE BOTANY, CHEMISTRY, MEDICINAL USES, SAFETY CONCERNS, AND LEGAL STATUS OF EPHEDRA AND ITS ALKALOIDS.

by Mark Blumenthal, Penny King

HerbalGram. 1995; 34:22 American Botanical Council

Few herbs have been as misunderstood as the classic Chinese herb ma huang. Popular belief holds that the herb has been commercially cultivated for its therapeutic properties longer than any other medicinal plant, although no confirmation of this is available in the literature. Despite over 2000 years of rational and accepted use in traditional medicine, due to its high potency and potential toxicity, ma huang has now become one of the most controversial herbs used in the United States today. Alkaloids and their salts from ma huang are approved by FDA as safe and effective ingredients in over-the-counter (OTC) drugs used for colds, flus, and respiratory allergies, including asthma. Numerous commercial herb products contain the whole herb ma huang or its extracts. These products are used for a variety of purposes, including aching muscles, arthritis, and edema, as well as energy and diet products -- most of which uses are not currently FDA approved (Dharmananda, 1995a). Concerns over the potency and safety of this herb and confusion between actions of ma huang and isolated alkaloids have prompted increased regulatory. scrutiny and an industry label warning.

BOTANY AND DISTRIBUTION

The primary species of ma huang, also sometimes called joint fir (Ephedra sinica) is a member of an evolutionarily primitive family of plants known as the Ephedraceae. There are 40 species in the genus Ephedra. E. equisetina is another Chinese/Mongolian species of commercial importance.

The plant has a pine-like odor and an astringent taste (Morton, 1977). There are several explanations for the origin of the Chinese name ma huang. Some authors refer to the term ma meaning astringent, due to the herb's numbing action on the tongue (Hsu, 1986); the term huang derives from the yellow color of the twigs (Tyler et al., 1988). However, another explanation is that ma means hemp, a reference to the plant's straw-like stems (Dharmananda, 1995b). To distinguish varieties, the Chinese have different prefixes for the names of five species of ephedra; for example, tsao-ma-huang refers to E. sinica, mu-tsei-ma-huang for E. equisetina, and san-mahuang for E. distachya. and so on (Hsu, 1986).

The plant is a low-growing, evergreen, almost leafless shrub that grows about 60 to 90 cm high (23.5 to 35.5 inches high). The stems are green, slender, erect, small-ribbed and channeled, about 1.5 mm in diameter, usually terminating in a sharp point. Small triangular leaves appear at the stem nodes which are about 4 to 65 cm apart (Tyler et al., 1988). The nodes are characteristically reddish brown. The stems usually branch from the base (Trease and Evans, 1986).

Ephedra species are native to China, Mongolia, India, parts of the Mediterranean, and North and Central America, although much of the commercial material comes not only from China, but also northwestern India and Pakistan (Tyler et al., 1988; Morton, 1977). E. gerardina, E. intermedia and E. major are found in India and Pakistan (Trease and Evans, 1986). E. major is a tall shrub that grows wild in Spain, Sicily, Afghanistan, and Pakistan (Morton, 1977).

E. gerardiana, a dwarf species (6 in. to 2 ft.), was formerly used in India for bronchial asthma and related conditions (USD in Tyler, 1993); it is native to the northwest Himalayas at high altitudes of 7,000 ft to 16,000 ft. in northern India, West Pakistan, Tibet, and Szechuan and Yunnan provinces of China (Morton, 1977).

There are ten Ephedra species in North America (Morton, 1977). E. nevadensis is native to the deserts of the American Southwest and was used as a tea by early settlers, hence the common names Mormon tea, Brigham tea, desert tea, teamster's tea, whorehouse tea, and squaw tea. The North American plants are reported to contain no pharmacologically active alkaloids (Lawrence Review, 1989); the same is true for Central American varieties (Tyler, 1994).

Several Ephedra species have been cultivated experimentally in Australia, Kenya, England, and the U.S. but, due to high labor costs compared to less technologically developed countries and other factors, these crops were not commercially successful (Morton, 1977).

TRADITIONAL USE

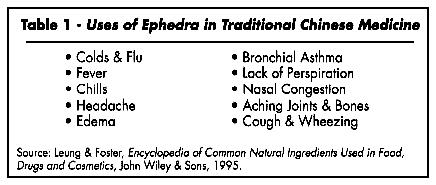

Ma huang, the dried stems of the ephedra plant, has been used in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM) for over 5,000 years. From a traditional energetics perspective, it "releases the exterior and disperses cold" and "facilitates the movement of lung qi and controls wheezing." (Bensky and Gamble, 1993.) It has a "pungent, mild, bitter flavor; warm property" and operates via the lung an bladder meridians (Hsu, 1986). In TCM ephedra is used for colds and flus, fever, chills, headache, edema, bronchial asthma, lack of perspiration (i.e., acts as a diaphoretic, to promote perspiration), nasal congestion, aching joints and bones, and coughs and wheezing (Leung and Foster, 1995).

TCM also employed ephedra root (called mahuanggen) an antisudorific (stops perspiration) in treatment of spontaneous and night sweating. The powdered root is now applied topically (e.g., to the feet) to treat excessive perspiration (Leung and Foster, 1995).

Ma huang has even been proposed as the source of soma, the divine plant revered by the Hindus and mentioned in ancient Vedic scriptures (Mahdihassan and Medhi, 1989).

CHEMISTRY

Ma huang usually contains a total of 0.5 to 2.5 percent of several alkaloids generally referred to as ephedra alkaloids (Lawrence Review, 1989). The dominant alkaloid is epbedrine, which usually comprises between 30 to 90 percent of total ephedra alkaloids, depending on the species (Lawrence Review, 1989).

Ratios of ephedrine to other alkaloids (e.g. pseudoephedrine, also called isoephedrine) vary according to species of Ephedra, time of year of harvest, weather conditions, and altitude where the plant grows. For example, one source lists total alkaloids for E. sinica at 1.31 percent with ephedrine at 1.12 percent (85.5 percent of total); E. major with up to 2.5 percent total alkaloids contains nearly 75 percent ephedrine. E. intermedia is low in ephedrine but relatively high in pseudoephedrine. Total alkaloids in E. gerardiana range from 0.8 percent to 1.4 percent, 50 percent being ephedrine, while E. equisetina is reported to contain about 1.75 percent total alkaloids with 1.58 percent (90 percent of total) being ephedrine (Morton, 1977). A more recent study of ephedra alkaloids shows the levels of individual and total alkaloids in twelve Ephedra species and varieties (Cui et al., 1991). This variation by species and other conditions explains why some commercial samples of the same brand of ma huang may show different ratios of ephedrine to pseudoephedrine and vary from one batch to another when analyzed chemically.

Ephedra alkaloids are stable. In the commercial trade for pharmaceutical use, a minimum level of 1.25 percent ephedrine was required (Morton, 1977). "Since ephedrine contains two asymmetrical carbon atoms, four compounds are possible. Only 1-ephedrine and racemic ephedrine are commonly used clinically; their pharmacological properties are essentially similar." (Goodman and Gilman, 1980.) Ephedrine alkaloids are isomeric, i.e., they contain the same number of each type of atom and the same empirical formula, but the spatial structural relationships of these atoms to each other as reflected in different optical rotation values. Isomeric forms of ephedrine include d- and l-ephedrine, and d- and l-pseudoephedrine, with mirror image pairs l-ephedrine and d-pseudoephedrine being the naturally occurring isomers (Merck, 1976).

Sources differ as to the original isolation of ephedrine. The earliest is cited by economic botanist Julia Morton as 1885 by G. Yamanashi at the Osada Experimental Station in Japan (Morton, 1977). However, Professor Varro E. Tyler writes that ephedrine was first isolated from ma huang by N. Nagai, a Japanese chemist, in 1887. At any rate, the isolated alkaloid first started appearing in the medical literature almost 40 years later in 1924 when K. C. Chen and his mentor C. F. Schmidt of the Peking Union College started publishing pharmacological studies on ephedrine. In the U.S. shortly thereafter, physicians began using the alkaloid as a nasal decongestant, CNS stimulant, and treatment for bronchial asthma (Tyler, 1994).

Ephedra also contains volatile oils which deteriorate after storage for one year. Alkaloid levels, however, remain stable for at least 2.5 years (Dharmananda, 1995b; Jia and Lu, 1988).

PHARMACOLOGY

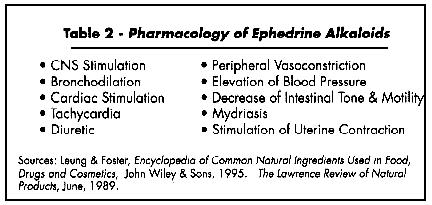

"Ephedrine is a potent sympathomimetic that stimulates alpha, beta(1) and beta(2) adrenergic receptors. It excites the sympathetic nervous system, causes vasoconstriction and cardiac stimulation, and produces effects similar to those of epinephrine (adrenalin). It produces a rather lasting rise in blood pressure, causes mydriasis [dilation of the pupil], and diminishes hyperemia [excess of blood in a body part]." (Tyler et al. 1988). Pseudoephedrine has shown strong diuretic activity in experiments on dogs and rabbits (Leung and Foster, 1995).

In conventional medicine ephedrine has advantages over epinephrine since it can be administered orally as well as by injection (Morton, 1977). However, the action of ephedrine compared to epinephrine in oral administration is its longer duration of action, more pronounced CNS actions, its hypertensive effect, and much lower potency. For example, the cardiovascular effects of ephedrine are similar to epinephrine but last about ten times longer (Goodman and Gilman, 1980).

TOXICOLOGY

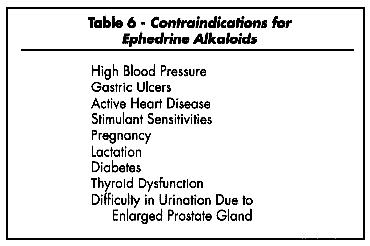

In large doses ephedrine causes nervousness, headaches, insomnia, dizziness, palpitations, skin flushing, and tingling, and vomiting (Lawrence Review, 1989). The Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs notes, "The principal adverse effects of ephedrine are CNS stimulation, nausea, tremors, tachycardia [rapid heartbeat], and urinary retention." (APhA 1986). An FDA advisory review panel on nonprescription cough, cold, allergy bronchodilator, and antiasthmatic drug products recommended that ephedrine be avoided by persons with heart disease, hypertension, thyroid disease, diabetes, or difficult urination due to enlarged prostate (APhA 1986).

"Since ephedrine causes the release of norepinephrine, the administration of ephedrine to a patient who has been receiving a monoamine oxidase inhibitor, which decreases the degradation and increases the storage of norepinephrine, could result in severe hypertension. Although this is a potentially fatal interaction, there is very little clinical information available." (APhA 1986.)

The British Herbal Pharmacopoeia (BHP) of 1983 offers the following warning for ma huang: "Although Ephedra does not produce, in therapeutic dosage, the marked pressor effect of ephedrine, it should not be used in hypertensive cases in the presence of coronary thrombosis or with monoamine oxidase [MAO] inhibitors." (BHP, 1983.)

THERAPEUTICS

The whole plant in crude or extract form has the following activity: antiasthmatic, bronchodilator, hypertensive, peripheral vasoconstrictor, sympathomimetic (stimulating the sympathetic nervous system) with alpha-and beta-adrenergic action, cerebral stimulant, and cardiac stimulant due to inotropic (affecting muscle contractility) action of pseudoephedrine (BHP, 1983). Other actions include mydriasis and decrease in intestinal tone and motility. Pseudoephedrine has activities similar to ephedrine except its hypertensive and CNS stimulation effects are weaker. Ephedrine has also been used in anaphylactic shock (Tang and Eisenbrandt, 1992) and (by injection) to prevent hypertension during anesthesia (Morton, 1977).

The indications for which the herb ma huang can be used include asthma, hay fever, urticaria (hives), enuresis (incontinence), narcolepsy (temporary attacks of deep sleep), and myasthenia gravis (progressive weakness of voluntary muscles) (BHP, 1983).

DOSAGE

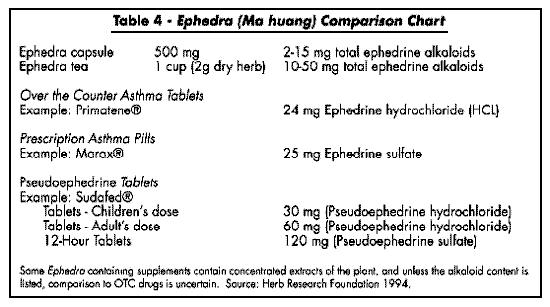

For therapeutic effect the BHP suggests ma huang preparations three times per day in the following dosage forms: a decoction of 1-4 grams dried stems; liquid extract (1:1) in 45% alcohol, 1-3 ml; tincture (1:4) in 45% alcohol, 6-8 ml (BHP, 1983). Ma huang can be made into a tea by decocting one heaping teaspoonful (about 2 grams) in one-half pint of boiling water for about 10 minutes. According to Tyler, if the tea is made from plant material of good quality (i.e., about 1.25 percent ephedrine or higher), the resultant tea should contain about 15 to 30 mg of ephedrine, which is close to the usually recommended and FDA approved dosage (Tyler, 1994). The FDA advisory panel recommended a maximum daily dosage of ephedrine of 150 mg per day, equivalent to 6 doses of 25 mg each (APhA, 1986). (For a listing of approved OTC drug dosages for ephedra alkaloids, see "Ephedra Comparison Chart.")

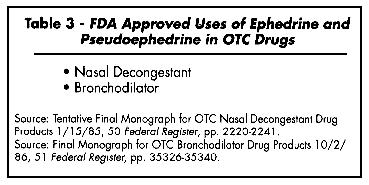

REGULATORY STATUS: OTC DRUG APPROVAL OF EPHEDRA ALKALOIDS

The FDA has approved several ephedra alkaloids and their salts as ingredients in over-the-counter (OTC) nasal decongestant and bronchodilator drugs. As a decongestant for oral ingestion in cases of common cold, hay fever, allergic rhinitis, upper respiratory allergies, and sinusitus, FDA approves pseudoephedrine hydrochloride and pseudoephedrine sulfate. For topical use for nasal congestion (i.e., in the form of nasal sprays) ephedrine and its salts (ephedrine hydrochloride, ephedrine sulfate, and racephedrine hydrochloride) are approved (FDA, 1985). For oral use pseudoephedrine is approved and generally preferred because it is less potent than ephedrine, causing less stimulation to the CNS. For bronchodilation in cases of mild asthmatic spasms, FDA approves ephedrine, ephedrine hydrochloride, ephedrine sulfate, and racephedrine hydrochloride (FDA, 1986).

Under the new Dietary Supplement Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA) ma huang, like most other herbs, is classified as a "dietary supplement." This would hold for powdered ma huang herb as well as its extracts and concentrates. Under DSHEA, FDA will probably have to prove that ma huang is not safe for normal use, even with warnings, in order to restrict its access to the market.

WEIGHT LOSS PRODUCTS AND THERMOGENESIS

Recently, ephedrine and ma huang have become subjects of scientific research for weight loss. This research and the case for "thermogenics," the burning of fat caused by dietary intake, are promoted in a recent book (Mowrey, 1994). A proprietary formula containing the alkaloids ephedrine and caffeine plus aspirin has been studied at Harvard University. The research was reported in the proceedings of a special symposium on this issue in the International Journal of Obesity. One study resulted in a 2.2 kilogram weight loss over eight weeks for persons taking the formula 30 minutes prior to each meal. Another eight-week followup session after five months resulted in a weight loss of 3.2 kg. There were no reports of significant changes in heart rate, blood pressure, or other side effects (Daly et al. 1993). However, a leading authority has questioned this aspect of the study: "If the authors of that study reported no significant changes in heart rate, blood pressure, or other side e ffects during its course, then they were obviously not administering therapeutic doses of ephedrine -- or caffeine either, for that matter. The asserted dosage regimen and the asserted absence of changes in these parameters are simply incompatible" (Tyler, 1995b).

The apparent success of the reportedly patented thermogenic formula of ephedrine, caffeine, and aspirin (ECA) has led to the development of numerous herbal formulas that attempt to mimic the "ECA skeleton." These combinations include, of course, ma huang, plus cola nut (source of caffeine) and willow bark (source of salicylates, similar to aspirin). Some experts doubt that there are sufficient levels of salicylates present in white willow in some formulas to have much effect. FDA has expressed concern over herbal products based on this combination, alleging reports of adverse reactions. Mowrey argues that the ECA is safe and effective for thermogenesis (Mowrey, 1994).

FEDERAL AND STATE ACTIONS AGAINST MA HUANG AND EPHEDRINE: DEA CONCERNS: EPHEDRINE AS A PRECURSOR FOR ILLEGAL DRUGS

Recently, the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA) and several states have raised concerns over the potential uses of ephedrine in the manufacture of illicit drugs. Due to its chemical structure ephedrine can be utilized as a precursor material for the illegal manufacture of methamphetamine ("speed") and methcathinone (also known by its street name "cat"). This issue, combined with safety concerns by public health officials, has forced ma huang into the crucible of intensified regulatory activity. Some states have recently issued regulations or passed legislation that restricts the sale of products like the ephedrine-containing diet and energy pills. Consequently, ma huang, because it contains small levels of ephedrine and related alkaloids, also has been included in some of these restrictions.

The issue of conversion of ma huang into illicit drugs by chemical synthesis is interesting. The basic chemical structure of ephedra alkaloids and those of speed and cat are similar. Although it is theoretically possible to convert ephedrine into these illicit drugs, some academics have questioned the feasibility on an economic level. This argument says that the amount of ephedrine and related alkaloids naturally found in ma huang (about 0.5 to 2.0 percent) is simply too low to make such an enterprise profitable, even at the high prices normally associated with the illicit drug trade.

According to Tyler, "In view of the difficulties involved in extracting and purifying the relatively small concentrations of ephedrine from the ephedra herb, and the fact that the plant serves only as a minor source of the alkaloid anyway [in the commercial pharmaceutical market where ephedrine and pseudoephedrine are now chemically synthesized], restricting the availability of the herb, although well intended, seems an excessive measure." (Tyler, 1994). However, since writing this he has changed his opinion on this issue, primarily because an academic colleague has convinced him that it is economically feasible to use ma huang or OTC drugs containing ephedra alkaloids as precursors in the illicit manufacture of cat; that is, manufacturers of cat can still charge up to ten times the cost of the ma huang or the OTC drugs they use as starting material, plus the relatively low cost of the necessary chemical reagents (Tyler, 1995a; Maikal, 1995).

In February 1995, the DEA published an internal report titled "The Use and Availability of Ephedra Products in the United States" which attempts to document chemical information on ma huang products, their potential use in illicit production of methamphetamine, and its use or abuse as a stimulant (Hutchinson, 1995). The reports cites two instances where forensic chemists have determined that illicit batches of methamphetamine were synthesized from ma huang, one in Colorado, the other in California. DEA says that pseudoephedrine can also be used as a precursor for illicit drugs.

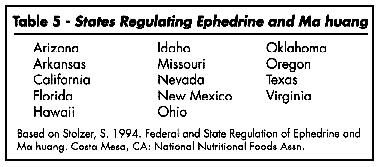

Several states that have recently passed new laws and/or issued regulations controlling the sale of ephedrine and/or ephedra products due to concerns about the illicit drug market potential are Florida, Missouri, and Oklahoma.

In Florida the situation is currently unclean as to whether ma huang is included. The new law effective May 29, 1994, controls all products containing ephedrine only as prescription drugs. OTC products containing pseudoephedrine are exempted. Ma huang in herbal products which do not make claims do not appear to be included but are under investigation.

In Missouri the law technically includes ma huang but it was intended to be aimed at ephedrine and related compounds. Ma huang is reportedly a low enforcement priority at this time.

Beginning about four years ago Nevada, Washington, and Arizona began to regulate the sale of ephedrine and/or ephedra more closely as prescription drugs. Exemptions were later made for ma huang products in Arizona and Nevada. In 1993 the Washington State Board of Pharmacy exempted ma huang and OTC drug products containing under 25 mg of total ephedrine.

MA HUANG IN OHIO

Regulatory activities in Ohio and Texas have focused on safety concerns, especially the use of ephedrine-containing stimulant pills which have become popular among high school children as stimulants and diet aids. Alarmed at the death of a 17-year-old high school football player who died from an overdose of pills containing ephedrine in an isolated, purified form, the Ohio legislature passed a law in July 1994 in an attempt control the availability of ephedrine stimulant pills. On November 14, 1994, new regulations went into effect that deem all products containing any level of ephedrine alkaloids, for whatever intended use, as schedule V controlled substances, requiring sale by licensed pharmacists to people 18 years of age or older. This is often termed "pharmacist only" or "behind-the-counter." The Ohio law mentions only ephedrine and related alkaloids but the Ohio Board of Pharmacy has defined ephedrine to include ma huang.

National Nutritional Foods Association (NNFA) filed a petition with the Ohio State Board of Pharmacy requesting that the board's ephedrine exemption regulations should permit exemption petitions for dietary supplement herbal products containing ma huang. This petition asks the board to exempt certain ma huang products from this regulation. NNFA suggests the following conditions for the sale of ma huang products: no sales to anyone under 18 years, the products should consist of single entity dietary supplements containing ma huang in non-extract form with no more than 1-2% total alkaloids by weight, and that supplements with ma huang combinations should be limited to 25 mg per dose. Finally, there should be signs in retail stores saying a person must be 18 years or older to purchase supplements containing ma huang.

While the petition is pending, NNFA has issued a bulletin to its members in Ohio reiterating its position that health food stores cannot currently sell products legally which contain ma huang and that such products should be pulled from the shelves.

SHOWDOWN IN TEXAS

In Texas concern by health officials about misuse of ephedrine was raised when several middle-school-aged girls were hospitalized after ingesting "Minithins," a stimulant product containing ephedrine.

Ma huang became a front-page issue in May 1994 after a woman in her early forties died while playing tennis in Austin, Texas. She had allegedly been using an herbal stimulant product called "Formula One," a product containing ma huang plus numerous other herbs, including cola nut (Cola nitida, which contains caffeine). There was no indication of the total ephedrine alkaloid content on the label.

U.S. FDA and Texas Department of Health officials have indicated concern over the possible synergy of ma huang combined with caffeine or caffeine-containing herbs. FDA claims to have received over 100 reports of adverse reactions related to Formula One in the past year (Anon., 1995a).

Formula One is sold by independent distributors through a network marketing system ("multi-level marketing"). The label carried a warning about some of the potential adverse effects including a statement that persons with a medical condition should consult a physician. The case of the dead woman and Formula One appears to have been inconclusive. No autopsy was conducted and it was unclear what quantity of the product she had consumed. Despite the Formula One's label warning, health officials became concerned about the potential for adverse reactions to the product. After news of the woman's death hit the papers around Texas, state health officials began to receive other reports alleging adverse reaction to the product.

Based on public health concerns, the Texas Department of Health attempted to ban Formula One. There was considerable legal maneuvering between the Texas Attorney General's Office and Formula One's manufacturer, Alliance USA of Richardson, Texas. In November 1994 FDA sent Alliance a warning letter saying that the product was a health hazard and unsafe, in an attempt to remove the product from the market. Afterward FDA asked Alliance to recall its product. FDA issued a public warning on the previous version of Formula One that contained the ma huang and cola nut combination (Anon, 1995a).

In March 1995 TDH published proposed regulations on the sale of ephedrine and ma huang-containing products. The action called for the prohibition of ma huang in dietary supplements except for its natural form, with total alkaloid content not to exceed 2.5%. Ma huang extracts would be prohibited in dietary supplements and natural ma huang would be prohibited as an ingredient with caffeine in the same product (Ward, 1995). Manufacturers would also be prohibited from marketing any ephedrine-containing product with claims for stimulation, energy, mental alertness, weight loss, appetite control, or any other purpose unapproved by FDA (Ward, 1995).

Motivated by concerns that the herb and health food industry trade associations were split on ma huang policy and strategy, a group of manufacturers, researchers, and industry attorneys calling themselves the Ad Hoc Committee on Ma Huang Safety met in Boulder, Colorado on April 18 to review toxicological data on ma huang and ephedrine and to plan a strategy to present their views at the public hearing at TDH on April 28.

About 100 people attended a public hearing at the Texas Department of Health building in Austin, Texas, on April 28. Those presenting testimony that tended to support the position that ma huang should still be allowed in consumer products in Texas included Rob McCaleb of the Herb Research Foundation; William Appler, an attorney representing the ad hoc committee; Daniel Mowrey, Ph.D., an author and researcher on ma huang and ephedrine in weight management; Neva Lindell, Executive Director of the NNFA -- Southwest Region; and consumers and numerous distributors of Formula One. Only one heating officer and a timekeeper were present from TDH. Testimony was presented that attempted to refute FDA's Hazard Analysis and Adverse Reaction Reports on ma huang, one of TDH's premises for its actions (Mergentime, 1995). HRF's McCaleb presented a lucid, rational position comparing ma huang liquid extract or concentrate to instant coffee and instant tea, to illustrate that ma huang, when added to water to make a beverage, contains the level of alkaloids that in the beverage is customarily found in teas brewed with dried ma huang stalks, just as a cup of coffee made from a freeze-dried concentrate contains a level of caffeine consistent with fresh-brewed coffee. (His complete remarks are found on page 27.) TDH was going to review the testimony and publish revised regulations in June for a 30-day comment period.

At press time, the Ad Hoc Committee on the Safety of Ma huang is preparing a submission to TDH which will include a safety review prepared by HRF, a review and analysis of FDA's adverse reaction report, and an additional analysis by Dr. Dennis Jones, a researcher/manufacturer in Canada (Brevoort, 1995).

HERB INDUSTRY POLICY

Prior to the Formula One incident in Texas, in March 1994 the American Herbal Products Association (AHPA) issued a policy statement which included a recommended wanting to be affixed to all herbal products containing ma huang. This policy, as later amended to raise the age limit from 13 to 18, is consistent with the usual medical precautions concerning the use of ephedra alkaloids:

"Seek advice from a health care practitioner prior to use if you are pregnant or nursing, or if you have high blood pressure, heart or thyroid disease, diabetes, difficulty in urination due to prostate enlargement, or if taking an MAO inhibitor or any other prescription drug. Reduce or discontinue use if nervousness, tremor, sleeplessness, loss of appetite or nausea occurs. Not for children under 18. KEEP OUT OF REACH OF CHILDREN." (AHPA, 1994; McGuffin, 1995)

In September 1994, AHPA sponsored a meeting in Baltimore where all manufacturers of ma huang products (whether AHPA members or not) were invited to discuss appropriate industry policy and development of analytical protocols for the chemical analysis of commercial ma huang products. AHPA held another similar meeting exclusively for manufacturers of ma huang products, co-sponsored with the NNFA, in December in Orlando, Florida. At this meeting additional concerns about ma huang were reportedly discussed including some revisions in the AHPA ma huang policy and further development of analytical techniques to attempt to determine whether any commercial ma huang materials might be "spiked" with synthetic ephedra alkaloids (McGuffin, 1994b).

The AHPA Board of Trustees extended the ma huang label warning from children under 13 to children under 18. AHPA and NNFA also considered amending the warning statement to include a limit on the amount of total ephedra alkaloids that should be present in each solid dosage unit and setting a maximum daily limit for total alkaloid ingestion which would be consistent with or lower than FDA's current level of allowable alkaloids in OTC drug products. AHPA members were given the opportunity to vote on this point in a memo sent to them on December 20 by Michael McGuffin, AHPA vice-president and Chair of the Standards Committee (McGuffin, 1994a). Membership response was divided and consequently, AHPA has not formally approved such action.

However, NNFA (which, unlike AHPA, is a national trade association of health food retailers, distributors, and manufacturers, only some of them herbal manufacturers) has adopted the policy of approving the label warning as originally developed by AHPA (as amended for 18-year-olds) but has taken the additional step to adopt measures that were discussed at the joint AHPA-NNFA meeting in Orlando. NNFA policy includes setting a limit on all ma huang-containing solid dosage forms (i.e., capsules and tablets) at 10 mg total alkaloids with the recommendation that not more than 20 mg be ingested at any time, with a limit of 60 mg total alkaloids ingestion per day (NNFA, 1995). How this policy is expected to be applied to liquid extracts atinctures containinging ma huang is not clear.

Both AHPA and NNFA have recommended that raw material suppliers and manufacturers refrain from using any ingredients which contain "added synthetically derived Ephedra alkaloids" and that member companies "analyze and verify, as soon as appropriate testing methods are validated" that there is no such material added to natural ma huang (McGuffin, 1994a; NNFA, 1995).

AHPA and NNFA have yet to resolve this difference in policy. Both organizations state that they are concerned about what they perceive to be in the best interests of the public and their respective members.

CONCLUSION

The foregoing discussion of ma huang raises some interesting questions for consumers of herbs, herb manufacturers and marketers, and state and federal regulators. What role, if any, can ma huang play as an ingredient in consumer products? To what extent is ma huang safe to use and at what dosage levels? Does the fact that the alkaloids in ma huang exhibit such potent and potentially toxic activity in isolated form and the fact that ma huang itself as an herb, either in crude form or especially in concentrated extracts, also shows considerable potency necessitate the total removal of ma huang from the marketplace, or would proper labeling and warnings be adequately protective? What about ephedrine-caffeine potential toxicity? Should caffeine be prohibited from ma huang products, and, if so, should FDA require warnings on caffeine beverages about the use of ephedrine and pseudoephrine-based OTC drugs, and vice versa? Should an upper limit of concentration of ma huang extracts be s tipulated in consumer products? Should total daily intake be indicated? Or, is ma huang simply too potent to be used without professional medical supervision?

Further, are there some benefits associated with the use of ma huang in addition to those the federal government allows for its alkaloids as OTC drug ingredients? Is there a proper role for ma huang in weight loss and diet products or in products designed to enhance energy and performance? Perhaps a new review of such considerations is in order.

In a society that is enamored with increasingly exotic varieties of coffee, the ma huang issue takes on a particular irony. Yes, ma huang and its ephedra alkaloids are generally more potent CNS stimulators than coffee and caffeine. Yes, ma huang and its alkaloids do have more generally agreed-upon contraindications than coffee and caffeine. But this is a question of degree. When viewed dispassionately, coffee and caffeine probably should be sold with some responsible label warnings. But coffee is generally recognized as a food and is sold without label warnings. Yet it is highly subject to abuse, producing hypertension, insomnia, irritability, and addiction in untold millions of Americans. A recent medical journal article on this subject referred to this phenomenon euphemistically as the "caffeine dependence syndrome" (Strain, 1994) -- a clear indication that caffeine is America's drag of choice and people are best advised not to meddle with America's favorite drug, even with i ts drawbacks. This comparison ought to provide some perspective and balance to the ma huang debate.

The questions surrounding the use of ma huang may not be easily answered. The real issue is one of responsible usage. Can consumers choose to use conventional foods, dietary supplements including herbal products, and even approved OTC drugs in ways that are not injurious to their health? Will consumers heed label warnings and other directions for responsible use? Can the herb industry develop and effectively maintain a policy of self-regulation that responsibly labels ma huang products, and protects the public health to an extent that satisfies regulators? At this point, the answers to these questions and the future for ma huang remains uncertain.

References:

American Herbal Products Assn. Policy Statement on Ephedra sinica (Ma huang). Austin, TX, March 30, 1994.

Anon. 1995a. FDA warns against using Nature's Nutrition Formula One. Pharmacy Today, Vol. 1, no. 8, April 15.

Anon. 1995b. Ma Huang Position Reiterated. Vitamin Retailer, April.

Anon. 1994. Ephedrine OTC Status Opposed by FDA Advisory Committee. The Tan Sheet. Nov. 21.

Anon. 1989. The Ephedras. Lawrence Review of Natural Products. June.

Bensky, D and Gamble, A. 1993. Chinese Herbal Medicine: Materia Medica, revised edition. Vista, CA: Eastland Press.

Brevoort, P. 1995. Personal communication, Jun 16.

British Herbal Pharmacopoeia. 1983. Bournemouth, England: British Herbal Medicine Assn.

Cui, J. F., Niu, C. Q., Zhang, J.S. 1991. GLC Determination of Ephedra Alkaloids in Mahuang. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica 26(11):852-857.

Daly, P. A. et al. 1993. Ephedrine, caffeine and aspirin: safety and efficacy for the treatment of human obesity. International Journal of Obesity 17 (Suppl 1):S73-S78

Dharmananda, S. 1995a. Personal communication. April 24.

Dharmananda, S. 1995b. Personal communication. April 25.

Dillard, C. 1994. Personal communication, December 6.

Evans, C. E. 1989. Trease and Evans' Pharmacognosy 13th ed. London: Bailleire Tindall.

Food and Drug Administration. Tentative Final Monograph for OTC Nasal Decongestant Drug Products. Federal Register 50 (Jan. 15, 1985): 2220-2241.

Food and Drag Administration. Final Monograph for OTC Bronchodilator Drug Products. Federal Register 50 (Oct.2, 1986): 35326-35340.

Gilman, A. G., Goodman, L. S., and Gilman, A. 1980. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, 6th ed. NY: MacMillan Publishing Co.

Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs,8th ed. 1986. Washington, DC: American Pharmaceutical Assn.

Herb Research Foundation. Ephedra (Ma huang) Comparison Chart. Boulder, CO.

Hsu, H. Y. 1986. Oriental Materia Medica: A Concise Guide. Long Beach, CA: Oriental Healing Arts Institute.

Hutchinson, K. 1995. The Use and Availability of Ephedra Products in the United States. Washington, DC: Drug and Chemical Evaluation Section, Office of Diversion Control, Drug Enforcement Administration, Feb. 23.

Jia, Y. Y. and F. X. Lu. 1988. Changes in alkaloids and volatile oil in Ephedra sinica due to shelving. Journal of Chinese Medicinal Materials, 11(3):38-40.

Leung, A. Y. and S. Foster. 1995. Common Natural Ingredients Used in Foods. Drugs and Cosmetics. NY: John Wiley (in press).

McGuffin, M. 1995. Personal communication, June 5.

McGuffin, M. 1994a. Memo to AHPA members. AHPA, Dec. 20.

McGuffin, M. 1994b. Personal communication, Dec. 7.

Mahdihassan, S. and Medhi, F.S. 1989. Soma of the Rigveda: An Attempt to Identify It. American Journal of Chinese Medicine 17, nos. 1-2:1-8.

Maikal, R. 1995. Personal communication, May 9.

The Merck Index. 1976. Rahway, NJ: Merck & Co.

Mergentime, K. 1995. Texas Moves to Ban Most Ma Huang Products. Natural Foods Merchandiser. June.

Morales, D. 1995. Morales Settles Case with Formula One. Office of the Attorney General, State of Texas. Press Release.

Morton, J. F. 1977. Major Medicinal Plant: Botany, Culture and Uses. Springfield, Il: Charles C. Thomas Publishers.

Mowrey, D. B. 1994. Fat Management: The Thermogenic Factor. Lehi, UT: Victory Publications.

National Nutritional Foods Assn. 1995. NNFA Announces Ma Huang (Ephedra) Policy. Feb. 8.

Stolzer, S. 1995. Personal communication, June 5.

Stolzer, S. 1994. Federal and State Regulation of Ephedrine and Ma Huang. Report to the National Nutritional Foods Association. Dec. 1.

Stolzer, S. 1994. Personal communication. Dec. 12.

Strain, E. C., G. Mumford, K. Silverman, and R. Griffiths. 1994. Caffeine dependence syndrome. Evidence from case histories and experimental evaluations. JAMA 272:1043-8.

Tyler, V. E. 1995a. Personal communication. May 2.

Tyler, V. E. 1995b. Personal communication. April 24.

Tyler, V. E. 1994. Herbs of Choice: The Therapeutic Use of Phytomedicinals. Binghamton, NY: Pharmaceutical Products Press.

Tyler, V. E. 1993. The Honest Herbal, 3d ed.Binghamton, NY: Haworth Press.

Tyler, V. E., L.R Brady, and J.E. Robbers, 1988.

Pharmacognosy ,9th ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger.

Ward, P. 1995. Health board proposes limits on ephedrine. Austin American-Statesman, Mar. 20.

Weil, A. 1995. Personal communication. May 11.

Article copyright American Botanical Council.

~~~~~~~~

By Mark Blumenthal and Penny King

|