Issue: 44 Page: 33-46

The Booming U.S. Botanical Market: A New Overview.

by Peggy Brevoort

HerbalGram. 1998; 44:33-46 American Botanical Council

"Take care with what you ask -- it may appear."This anonymous quote could well describe the evolution of the U.S. market for medicinal botanicals. In the early 1970s a handful of dedicated individuals began selling medicinal herbs to each other and a limited consumer following, signaling the birth of the herb industry we know today. Their vision was the acceptance of these products by the mainstream American consumer and mainstream American health care. Today the market is purported to approach US $4 billion at retail with the fastest-growing documented segment in the mass market (supermarket, drug, and mass merchandise) increasing at an annualized rate of over 100 percent (International Research Institute (IRI) 52-week period ending July 12, 1998).  U.S. Botanical Market Update

Dateline, U.S.A., Fall 1998

OVERVIEW

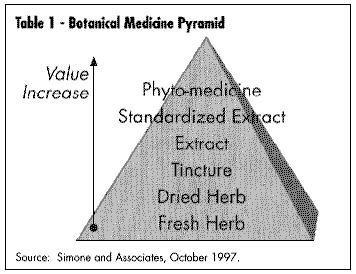

In 1994, we estimated the market for botanical medicines to be approximately $1.6 billion annual retail sales. Today this figure is estimated to be approaching $4 billion at retail Botanical medicines are available in almost any retail outlet from Walgreen's to Walmart to the comer grocery. Channels for sales of medicinal botanicals include mail order catalog sales, club store sales (i.e., Sam's Warehouse) multi-level sales (from companies such as Amway, Shaklee, Nature's Sunshine, Nu Skin International, Shaperite); sales within specific ethnic communities (Asian, Latino); directly from a health care practitioner (whether they are Western M.D.s or complementary practitioners such as acupuncturists, naturopaths, chiropractors); sales through military bases; and the newest category, sales over the Internet. The natural foods market still boasts the largest selection and variety of these products with literally hundreds of products being offered either as whole herbs, tinctures, e xtracts or standardized products (See Table 1 - Botanical Composition Pyramid).

This pyramid illustrates the increasing concentration of finished product that results from various types of processing techniques. A more concentrated and expensive product results from a more complex manufacturing processes. Thus the top of the pyramid represents a phytomedicine such as ginkgo, which is standardized to only two groups of marker compounds and sometimes eliminating some other compounds in the process. Manufacturing a standardized extract means that the material has been "standardized" to one or more chemical "markers" (not necessarily the "active" ingredients). Creating a tincture is a simple process of infusing herbs in alcohol, while an extract requires heating and greater concentration of the original material. Conversely, chamomile tea is at the bottom of the pyramid as bulk-dried material or in tea bags.

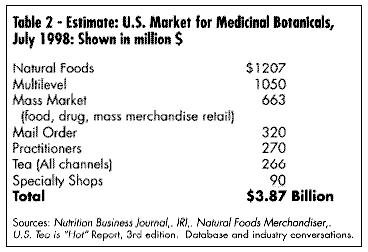

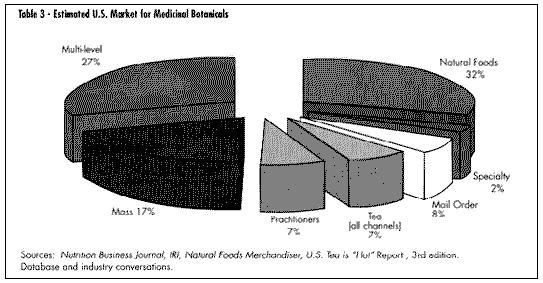

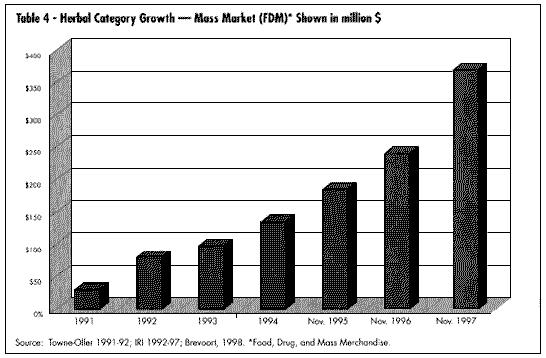

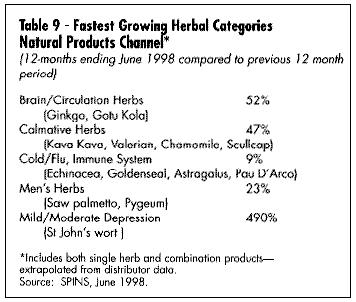

Mass market sales (food, drag, and mass merchandise outlets) have seen the greatest documented growth in sales. The past two years have seen a substantial development in electronic scanning of these products through the mass market channel. International Research Institute (IRI) is the main conduit for this data, which can be purchased by interested companies. Beginning in January 1998, Spence Information Services (SPINS) of San Francisco expanded its services to include not only analysis of natural food distributor sales of botanical products, but also scanned data from major natural product chains such as Whole Foods and Wild Oats. (See Table 2, U.S. Market for Medicinal Botanicals, Table 3,Estimated U.S. Market for Medicinal Botanicals, Table 4, Herbal Category Growth, and Table 9, Fastest Growing Herbal Categories Natural Products Channel.)

U.S. Botanical Market Update

Dateline, U.S.A., Fall 1998

OVERVIEW

In 1994, we estimated the market for botanical medicines to be approximately $1.6 billion annual retail sales. Today this figure is estimated to be approaching $4 billion at retail Botanical medicines are available in almost any retail outlet from Walgreen's to Walmart to the comer grocery. Channels for sales of medicinal botanicals include mail order catalog sales, club store sales (i.e., Sam's Warehouse) multi-level sales (from companies such as Amway, Shaklee, Nature's Sunshine, Nu Skin International, Shaperite); sales within specific ethnic communities (Asian, Latino); directly from a health care practitioner (whether they are Western M.D.s or complementary practitioners such as acupuncturists, naturopaths, chiropractors); sales through military bases; and the newest category, sales over the Internet. The natural foods market still boasts the largest selection and variety of these products with literally hundreds of products being offered either as whole herbs, tinctures, e xtracts or standardized products (See Table 1 - Botanical Composition Pyramid).

This pyramid illustrates the increasing concentration of finished product that results from various types of processing techniques. A more concentrated and expensive product results from a more complex manufacturing processes. Thus the top of the pyramid represents a phytomedicine such as ginkgo, which is standardized to only two groups of marker compounds and sometimes eliminating some other compounds in the process. Manufacturing a standardized extract means that the material has been "standardized" to one or more chemical "markers" (not necessarily the "active" ingredients). Creating a tincture is a simple process of infusing herbs in alcohol, while an extract requires heating and greater concentration of the original material. Conversely, chamomile tea is at the bottom of the pyramid as bulk-dried material or in tea bags.

Mass market sales (food, drag, and mass merchandise outlets) have seen the greatest documented growth in sales. The past two years have seen a substantial development in electronic scanning of these products through the mass market channel. International Research Institute (IRI) is the main conduit for this data, which can be purchased by interested companies. Beginning in January 1998, Spence Information Services (SPINS) of San Francisco expanded its services to include not only analysis of natural food distributor sales of botanical products, but also scanned data from major natural product chains such as Whole Foods and Wild Oats. (See Table 2, U.S. Market for Medicinal Botanicals, Table 3,Estimated U.S. Market for Medicinal Botanicals, Table 4, Herbal Category Growth, and Table 9, Fastest Growing Herbal Categories Natural Products Channel.) GROWTH OF MARKET

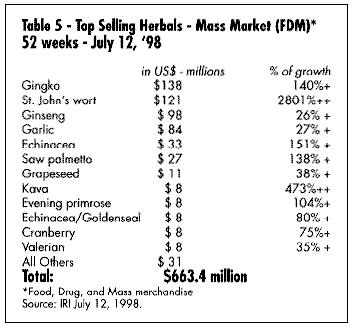

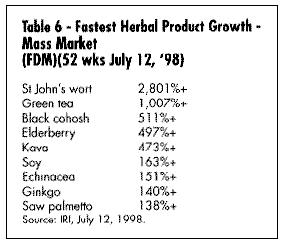

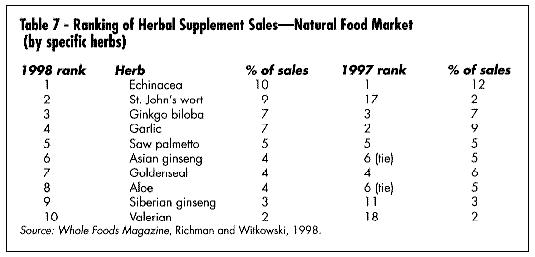

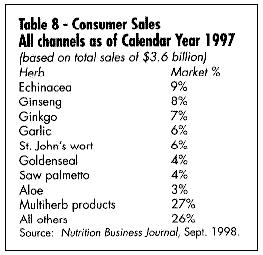

What are the best-selling and fastest-growing products in the U.S. today? Table 5 gives a summary of the best-selling products in the mass market (according to the IRI), and Table 6 gives a list of the fastest-growing. Table 7 shows the best-selling according to a Whole Foods Magazine Survey published in October 1998 (Richman and Witkowski, 1998). Table 8 shows the top-selling herbal products in the U.S. Table 9 shows the fastest-growing herbal categories in natural foods.

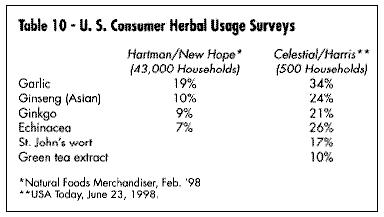

In early 1998, Hartman & New Hope, a consumer-based research organization, conducted an in-depth study of 43,000 U.S. households using dietary supplements and came up with a list of some of the most widely used products. The studies by Hartman & New Hope and Celestial (Harris) are shown in Table 10.

Herbs are not only sold in conventional delivery systems of capsules, tablets, liquid extracts, and teas, but are also appearing as healthy ingredients in conventional foods. This new category of "nutraceuticals" (a term coined by Dr. Steven DeFelice) encompasses any food ingredient which is taken for its health-giving properties, from ginkgo potato chips to ginseng candy bars, Chinese herb cereal, echinacea fruit drink, and kava corn chips. The only limit seems to be determined by what consumers' taste buds will bear (or what regulators will tolerate).

Unique delivery systems are also emerging -- from a St. John's Wort transdermal patch to yam cream for estrogen therapy, or a sustained-release herbal formula, or one that has been micro-encapsulated for immediate absorption.

SUPPLY

As the demand for these products escalates, supply of quality raw material becomes a key factor. For example, the recent surge in demand for Echinacea, St. John's wort, and kava, has stressed supply, causing price increases resulting in confusion for growers, many of whom are new to the commercial market for these products.

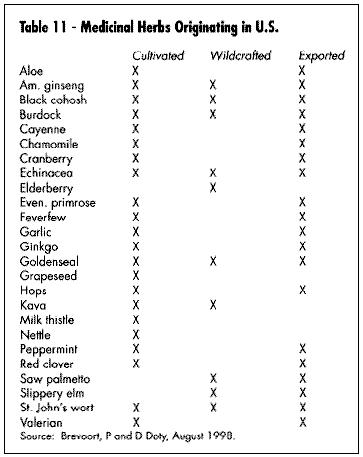

Sustained yield of these botanical product raw materials takes on additional importance: in 1997, Convention in Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) listed goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis), a primarily wildcrafted product indigenous to the U.S., under Appendix II ("threatened" status) in order to more closely regulate supply in world trade (Bannerman, 1997). Table 11 is an updated chart of major medicinal herbs harvested in the U.S.

Several organizations in the U.S. have taken on the task of monitoring and preserving important wild species growing in North America. United Plant Savers (UPS) of Stowe, Vermont, is developing a stewardship program, and Frontier Herbs in Norway, Iowa, has set aside 600 acres for medicinal plant crop investigation and propagation in Ohio. TRAFFIC USA, a division of World Wildlife Fund, has issued reports on threatened medicinal plants (Robbins, 1998).

ADVERTISING

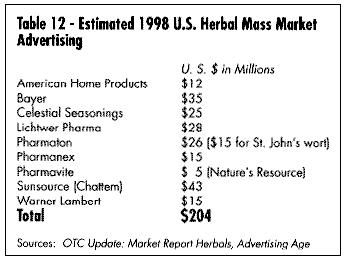

One of the most compelling reasons for the rapid growth in this market, particularly in the mass market channels, has been the substantial investment in advertising dollars by large companies entering the market. When botanicals were mainly in the venue of the natural foods industry, advertising budgets approaching $500,000 $1,000,000 were considered extravagant. Prior to the Sunsource expenditure for Ginsana of $230,000 in 1987-88, (Rosenthal, 1998) few dollars were spent on advertising in the mass market channels. Table 12 shows some of this year's published figures for advertising. Companies with deep resources and accustomed to large advertising budgets for mass market launch have changed the industry because they have brought an increased awareness of these products to the average American.

As these products become more visible, free advertising in the form of news specials has worked to increase market awareness. Beginning with the May 1997 Time magazine cover story on Dr. Andew Weil and his herbal medicine chest, then ABC's 20/20 and the Wall Street Journal's specials on kava, 20/20's and Newsweek specials on St. John's wort, and the Wall Street Journal's coverage of Echinacea, sales of these products have accelerated dramatically, often beyond the manufacturer's ability to supply products. Initially, the herbal industry saw television and other media as bearers of negative reportage. As more clinical work is done in this area (i.e., the meta-analysis of St. John's wort clinical trials reported in 1996 in the British Medical Journal), more positive publicity results. The main concern today for companies is not necessarily negative publicity but rather scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) over increasingly specific advertising claims based on a company 's interpretation of the Dietary Supplement and Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA).

GROWTH OF MARKET

What are the best-selling and fastest-growing products in the U.S. today? Table 5 gives a summary of the best-selling products in the mass market (according to the IRI), and Table 6 gives a list of the fastest-growing. Table 7 shows the best-selling according to a Whole Foods Magazine Survey published in October 1998 (Richman and Witkowski, 1998). Table 8 shows the top-selling herbal products in the U.S. Table 9 shows the fastest-growing herbal categories in natural foods.

In early 1998, Hartman & New Hope, a consumer-based research organization, conducted an in-depth study of 43,000 U.S. households using dietary supplements and came up with a list of some of the most widely used products. The studies by Hartman & New Hope and Celestial (Harris) are shown in Table 10.

Herbs are not only sold in conventional delivery systems of capsules, tablets, liquid extracts, and teas, but are also appearing as healthy ingredients in conventional foods. This new category of "nutraceuticals" (a term coined by Dr. Steven DeFelice) encompasses any food ingredient which is taken for its health-giving properties, from ginkgo potato chips to ginseng candy bars, Chinese herb cereal, echinacea fruit drink, and kava corn chips. The only limit seems to be determined by what consumers' taste buds will bear (or what regulators will tolerate).

Unique delivery systems are also emerging -- from a St. John's Wort transdermal patch to yam cream for estrogen therapy, or a sustained-release herbal formula, or one that has been micro-encapsulated for immediate absorption.

SUPPLY

As the demand for these products escalates, supply of quality raw material becomes a key factor. For example, the recent surge in demand for Echinacea, St. John's wort, and kava, has stressed supply, causing price increases resulting in confusion for growers, many of whom are new to the commercial market for these products.

Sustained yield of these botanical product raw materials takes on additional importance: in 1997, Convention in Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) listed goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis), a primarily wildcrafted product indigenous to the U.S., under Appendix II ("threatened" status) in order to more closely regulate supply in world trade (Bannerman, 1997). Table 11 is an updated chart of major medicinal herbs harvested in the U.S.

Several organizations in the U.S. have taken on the task of monitoring and preserving important wild species growing in North America. United Plant Savers (UPS) of Stowe, Vermont, is developing a stewardship program, and Frontier Herbs in Norway, Iowa, has set aside 600 acres for medicinal plant crop investigation and propagation in Ohio. TRAFFIC USA, a division of World Wildlife Fund, has issued reports on threatened medicinal plants (Robbins, 1998).

ADVERTISING

One of the most compelling reasons for the rapid growth in this market, particularly in the mass market channels, has been the substantial investment in advertising dollars by large companies entering the market. When botanicals were mainly in the venue of the natural foods industry, advertising budgets approaching $500,000 $1,000,000 were considered extravagant. Prior to the Sunsource expenditure for Ginsana of $230,000 in 1987-88, (Rosenthal, 1998) few dollars were spent on advertising in the mass market channels. Table 12 shows some of this year's published figures for advertising. Companies with deep resources and accustomed to large advertising budgets for mass market launch have changed the industry because they have brought an increased awareness of these products to the average American.

As these products become more visible, free advertising in the form of news specials has worked to increase market awareness. Beginning with the May 1997 Time magazine cover story on Dr. Andew Weil and his herbal medicine chest, then ABC's 20/20 and the Wall Street Journal's specials on kava, 20/20's and Newsweek specials on St. John's wort, and the Wall Street Journal's coverage of Echinacea, sales of these products have accelerated dramatically, often beyond the manufacturer's ability to supply products. Initially, the herbal industry saw television and other media as bearers of negative reportage. As more clinical work is done in this area (i.e., the meta-analysis of St. John's wort clinical trials reported in 1996 in the British Medical Journal), more positive publicity results. The main concern today for companies is not necessarily negative publicity but rather scrutiny from the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) over increasingly specific advertising claims based on a company 's interpretation of the Dietary Supplement and Health and Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA). HEALTH CARE COVERAGE

When Dr. David Eisenberg published his study on American usage of alternative health care in 1993, he noted there was nonexistent coverage by insurance for these services or products (Eisenberg, 1993). Today at least a dozen national insurance companies cover services for acupuncture, naturopathy, and chiropractic care. In some cases, this will include reimbursement for doctor prescribed nutritional supplements (including botanicals). American Specialty Health Plans of San Diego, California, recently announced coverage of a complete line of Chinese herbal formulas, manufactured in the U.S. by a Taiwanese pharmaceutical company. In 1997, Oxford Health instituted catalog sales of dietary supplements at greatly reduced prices for its subscribers/patients.

More health practitioners are being trained in botanical medicine. Columbia University is now conducting two one-week long botanical training courses for M.D.s, and Harvard holds one weeklong course per year on alternative medicine, including botanicals, both with C.M.E. credits. Harvard and Columbia have established departments for Alternative Medicine, and Harvard Medical School runs an intensive month long course on alternative health care for undergraduates. The University of Arizona runs a two-year training program in "integrative" medicine for graduate M.D.s.

There are two accredited Naturopathic Colleges in the U.S.: Bastyr University in Seattle, Washington, and the National College of Naturopathic Medicine in Portland, Oregon. Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine in Scottsdale, Arizona, has applied for accreditation. Each offers a complete curriculum in botanical medicine. Eleven states now allow the practice of naturopathy. There are over 1,500 naturopathic physicians in the U.S. (American Association of Naturopatic Physicians). There are at least 22 accredited colleges of Oriental medicine offering training in acupuncture and oriental botanical medicine. It is estimated there are 8,500 licensed acupuncturists in the U.S. today, and at least 36 states allow the practice.

In 1997, Dr. Larry Kincheloe in Oklahoma City did a small survey of the cost savings associated with usage of botanical medicine instead of pharmaceuticals in his clinic. His conservative estimate showed a savings in direct yearly drug costs of between $500,000-$750,000 for his clinic, which contracts to cover 60,000 members of an HMO (Kincheloe, 1998).

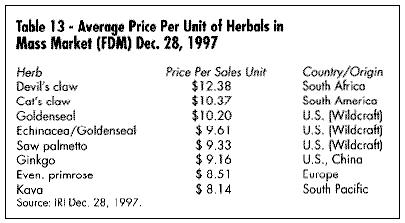

Table 13 looks at the average cost of 10 of the most expensive herb products in the mass market, based on IRI data. An interesting comparison -- in 1996 the national average price of a prescription for a conventional drug was $32.90 (IMS Market View -- Novartis Pharmacy Benefit Report).

One result of the increased number of botanical medicines in the mass market, particularly pharmacy, is the pharmacists' demand for more accurate botanical information. Since pharmacognosy is no longer routinely taught at pharmacy schools, industry has had to step in to fill the gap. According to a survey conducted at the Center for Food Marketing, St. Joseph's University, Philadelphia, every one of the 300+ pharmacists interviewed said they were queried about herbals by their customers (Childs, 1998). Several Continuing Education Courses on botanical medicine are now offered to pharmacists and even the trade journals now run regular articles, such as:

- "A Pharmacist's guide to the safe and effective use of medicinal herbs" (Retail Pharmacy News, April 1998)

- "Top 10 Questions to ask patients before recommending herbal remedies" (Drug Topics, April 20, 1998)

- "An Herbal Update Information and Test for Pharmacists" (developed by the University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy, Drug Topics, June 1, 1998)

HEALTH CARE COVERAGE

When Dr. David Eisenberg published his study on American usage of alternative health care in 1993, he noted there was nonexistent coverage by insurance for these services or products (Eisenberg, 1993). Today at least a dozen national insurance companies cover services for acupuncture, naturopathy, and chiropractic care. In some cases, this will include reimbursement for doctor prescribed nutritional supplements (including botanicals). American Specialty Health Plans of San Diego, California, recently announced coverage of a complete line of Chinese herbal formulas, manufactured in the U.S. by a Taiwanese pharmaceutical company. In 1997, Oxford Health instituted catalog sales of dietary supplements at greatly reduced prices for its subscribers/patients.

More health practitioners are being trained in botanical medicine. Columbia University is now conducting two one-week long botanical training courses for M.D.s, and Harvard holds one weeklong course per year on alternative medicine, including botanicals, both with C.M.E. credits. Harvard and Columbia have established departments for Alternative Medicine, and Harvard Medical School runs an intensive month long course on alternative health care for undergraduates. The University of Arizona runs a two-year training program in "integrative" medicine for graduate M.D.s.

There are two accredited Naturopathic Colleges in the U.S.: Bastyr University in Seattle, Washington, and the National College of Naturopathic Medicine in Portland, Oregon. Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine in Scottsdale, Arizona, has applied for accreditation. Each offers a complete curriculum in botanical medicine. Eleven states now allow the practice of naturopathy. There are over 1,500 naturopathic physicians in the U.S. (American Association of Naturopatic Physicians). There are at least 22 accredited colleges of Oriental medicine offering training in acupuncture and oriental botanical medicine. It is estimated there are 8,500 licensed acupuncturists in the U.S. today, and at least 36 states allow the practice.

In 1997, Dr. Larry Kincheloe in Oklahoma City did a small survey of the cost savings associated with usage of botanical medicine instead of pharmaceuticals in his clinic. His conservative estimate showed a savings in direct yearly drug costs of between $500,000-$750,000 for his clinic, which contracts to cover 60,000 members of an HMO (Kincheloe, 1998).

Table 13 looks at the average cost of 10 of the most expensive herb products in the mass market, based on IRI data. An interesting comparison -- in 1996 the national average price of a prescription for a conventional drug was $32.90 (IMS Market View -- Novartis Pharmacy Benefit Report).

One result of the increased number of botanical medicines in the mass market, particularly pharmacy, is the pharmacists' demand for more accurate botanical information. Since pharmacognosy is no longer routinely taught at pharmacy schools, industry has had to step in to fill the gap. According to a survey conducted at the Center for Food Marketing, St. Joseph's University, Philadelphia, every one of the 300+ pharmacists interviewed said they were queried about herbals by their customers (Childs, 1998). Several Continuing Education Courses on botanical medicine are now offered to pharmacists and even the trade journals now run regular articles, such as:

- "A Pharmacist's guide to the safe and effective use of medicinal herbs" (Retail Pharmacy News, April 1998)

- "Top 10 Questions to ask patients before recommending herbal remedies" (Drug Topics, April 20, 1998)

- "An Herbal Update Information and Test for Pharmacists" (developed by the University of Mississippi School of Pharmacy, Drug Topics, June 1, 1998) According to Nicholas Hall in his July 1998 OTC report on the U.S. herbal market, although in the past botanicals were treated as an extension of the vitamin and mineral lines, today, with increased emphasis on structure and function claims allowed under DSHEA, products are being rearranged by claims as consumers become more familiar with studies on these products.

DEFINITIONS

Although DSHEA lists both "herbs" and "botanicals" in its coverage, the more accurate term is botanical -- "a substance derived from plants, a vegetable drug, especially in its crude state" -- whereas "herb" technically (in botany) refers only to a plant with a non-woody stem that dies back in winter. One of the first lessons a company entering this field must grasp is that different plant parts are used in different species, for example: goldenseal root, ginkgo leaf, saw palmetto berry. In Chinese medicine, often different plant parts have different medicinal effects, ginseng leaf and ginseng root being one example.

REGULATORY CATEGORIES

DSHEA now regulates botanical medicines as dietary supplements, defined as "a vitamin, a mineral, an herb or other botanical (or) an amino acid." There are several other regulatory avenues for botanicals -- none as widely accepted today. First, botanicals can be sold as foods. Of course, many are sold as that: as flavorings (parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme) or alone -- candied ginger, pickled garlic, jalape¤o peppers, etc.

Second, they can be sold as dietary supplements with claims as to their effect on the structure or function of the human body, providing the company has adequate documentation for the claim. The product must display the disclaimer, "This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease."

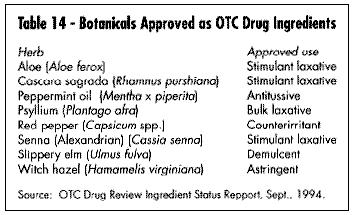

The third regulatory category is as an approved OTC medication. Table 14 lists the botanicals currently in this category. This does not mean they cannot be sold as dietary supplements, rather that they can in addition carry more specific therapeutic (i.e., drug) claims. In 1992 the European-American Phytomedicines Coalition (EAPC) made formal application to the FDA OTC drug division that European phytomedicines be reviewed as old drugs based on their extensive usage in Europe. In 1993 and 1994 EAPC petitioned FDA to allow valerian to be reviewed in the night-time sleep aid category and ginger in the anti-nauseant category, respectively. (Blumenthal, 1995); Pinco & Israelsen, 1994; Pinco & Israelsen, 1995). FDA has not yet responded to these petitions.

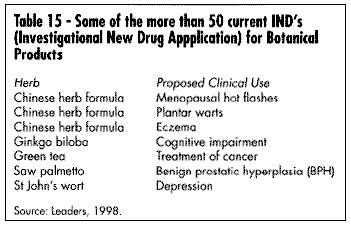

The fourth regulatory category available for botanicals is via the IND/NDA (Investigational New Drug/New Drug Application) process, formerly the purview only of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry.

To date, according to sources within FDA's CDER (Center for Drug Evaluation and Research), there are 50 botanicals or botanical formulas holding active IND applications. Table 15 lists some of these products. Dr. Robert Temple, Director of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation, has commented on this regulatory route for botanicals:

"A long history of safe use might provide sufficient safety information for products that are intended for short-term use. For something that's given only briefly...for short-term, you may consider the history of exposure, if it can be documented recently, as relevant safety. However, [it is still] questionable whether a history of safe use would be adequate to support the safety of an ingredient intended for regular, long-term use.

"FDA is willing to address clinical trials for traditional herbal products differently from drug trials....What we've proposed is that initial short-term controlled trials for materials marketed under DSHEA...would need little or no chemistry or toxicology data. The agency is attempting to reduce the obstacles to conducting clinical trials for herbal products.

"We don't have a rule that people who carry out trials have to be physicians. I don't see why someone with [an herbal] background couldn't carry out the trial. Someone who's experienced in [herbal] use, and believes that certain things are true is probably the best person to help design the trial. You can test Eastern philosophy in a Western controlled trial." (Temple, 1996.)

Prior to the passage of DSHEA, Loren Israelsen, Director of the Utah Natural Products Alliance, called the IND process for botanicals a "roach motel: easy to get in, but you never get out." (Israelson, 1998) Today, Mr. Israelsen feels that the IND process is still an obstacle course, but possible to surmount with the right product. Time will tell who is correct. Certainly the first botanical product to obtain prescription status will have tremendous effect on the industry. In response to this new regulatory channel, several divisions of FDA, under the direction of CDER, have developed a document for the development of botanical drugs. According to sources within FDA, this document, previously expected in November 1997, is due to be published in the fall of 1998.

The last category, as yet undeveloped, is that of a separate "traditional medicine" application for botanicals. This differentiation is accepted in many other parts of the world and endorsed as well by World Health Organization (WHO), which states:

"A guiding principle should be that if the product has been traditionally used without demonstrated harm no specific restrictive regulatory action should be undertaken unless new evidence demands a raised risk-benefit assessment. As a basic rule, documentation of a long period of use should be taken into consideration when safety is being assessed. This means that, when there are no detailed toxicological studies, documented experience on long term use without evidence of safety problems should form the basis of the risk assessment." (WHO, 1992)

Discussions within the industry and academia continue on the possible development of this new category.

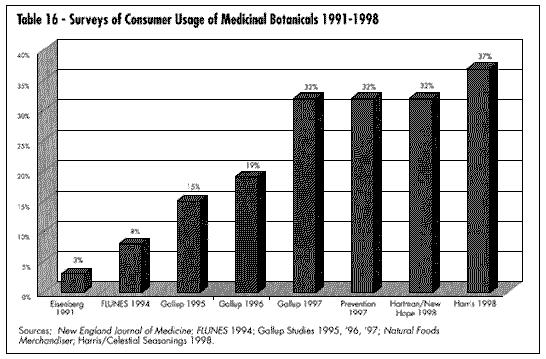

CONSUMER ATTITUDES

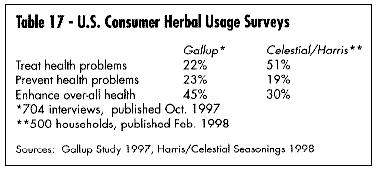

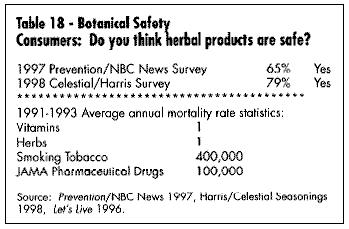

One of the most important elements in understanding and developing the market for medicinal botanicals is current consumer attitudes. It is significant that Prevention Magazine, the Gallup Polls, New Hope Communication (publisher of several natural products industry magazines), and many individual companies (Celestial Seasonings, Warner Lambert, Leiner Health Products) have done extensive consumer polling in regards to acceptance and understanding of botanicals. Tables 16 and 17 show consumers' use of these products; Table 18 shows data on their safety. It is apparent that consumer survey data can vary widely depending on the questions asked, survey methodology, and sample population. The significance here is that the industry is now large enough to warrant investigation by major consumer survey companies.

STANDARDS PROJECTS

As the U.S. industry increases in sophistication for the use of these products, more demand for quality and standardization emerges. The American Botanical Council (ABC) has just published its translation of The Complete German Commission E Monographs -- Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. The European Scientific Cooperative on Phytomedicine (ESCOP) has developed 50 monographs on botanicals (Blumenthal, 1997). WHO now has 28 monographs in Volume I and another 30 monographs in preparation for Volume II (Phytopharm Consulting).

In the U.S., the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia has published an extensive monograph on St. John's wort (Upton, 1997) and hopes to publish six more monographs by early 1999. Two of these -- Hawthorn and Valerian -- are in completion stage. The other four nearing completion are: Astragalus, Schizandra, Willow, and Reishi.

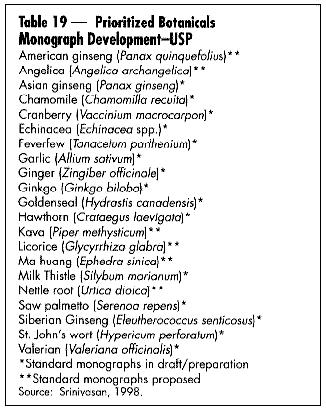

The U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) held its second conference on botanical standards this past August. The USP currently has prioritized 21 botanicals for monograph development (Table 19). Many botanicals were originally listed in the USP only to be discontinued because of lack of use.

The American Herbal Products Association (AHPA), the U.S. trade association for herbal product manufacturers, has published two important books. Herbs of Commerce is a listing of 600 of the most used botanicals, common name, and Latin binomial (Foster, 1992). This document has been cited by FDA in its regulations for implementation of DSHEA as the authoritative text for label nomenclature (21 CFR 101, 4(h)(2)). The second edition of this book will be available in late 1998, and will have over 1800 entries. AHPA has also published The Botanical Safety Handbook, a guide to use of botanical ingredients (McGuffin et al., 1997). It classifies the same 600+ botanicals into four categories, based on extensive literature review:

"Class 1 - Herbs which can be safely consumed when used appropriately.

Class 2 - Herbs for which the following use restrictions apply, unless otherwise directed by an expert qualified in the use of the described substance:

2a: For external use only

2b: Not to be used during pregnancy

2c: Not to be used while nursing

2d: Other specific use restrictions as noted

Class 3 - Herbs for which significant data exist to recommend the following labeling:

`To be used only under the supervision of an expert qualified in the appropriate use of this substance.' Labeling must include proper use information: dosage, contraindications, potential adverse effects and drug interactions, and any other relevant information related to the safe use of the substance.

Class 4 - Herbs for which insufficient data are available for classification." (McGuffin, et al., 1997) (See review in HerbalGram No. 40. pp. 59-60.)

According to Nicholas Hall in his July 1998 OTC report on the U.S. herbal market, although in the past botanicals were treated as an extension of the vitamin and mineral lines, today, with increased emphasis on structure and function claims allowed under DSHEA, products are being rearranged by claims as consumers become more familiar with studies on these products.

DEFINITIONS

Although DSHEA lists both "herbs" and "botanicals" in its coverage, the more accurate term is botanical -- "a substance derived from plants, a vegetable drug, especially in its crude state" -- whereas "herb" technically (in botany) refers only to a plant with a non-woody stem that dies back in winter. One of the first lessons a company entering this field must grasp is that different plant parts are used in different species, for example: goldenseal root, ginkgo leaf, saw palmetto berry. In Chinese medicine, often different plant parts have different medicinal effects, ginseng leaf and ginseng root being one example.

REGULATORY CATEGORIES

DSHEA now regulates botanical medicines as dietary supplements, defined as "a vitamin, a mineral, an herb or other botanical (or) an amino acid." There are several other regulatory avenues for botanicals -- none as widely accepted today. First, botanicals can be sold as foods. Of course, many are sold as that: as flavorings (parsley, sage, rosemary and thyme) or alone -- candied ginger, pickled garlic, jalape¤o peppers, etc.

Second, they can be sold as dietary supplements with claims as to their effect on the structure or function of the human body, providing the company has adequate documentation for the claim. The product must display the disclaimer, "This statement has not been evaluated by the Food and Drug Administration. This product is not intended to diagnose, treat, cure, or prevent any disease."

The third regulatory category is as an approved OTC medication. Table 14 lists the botanicals currently in this category. This does not mean they cannot be sold as dietary supplements, rather that they can in addition carry more specific therapeutic (i.e., drug) claims. In 1992 the European-American Phytomedicines Coalition (EAPC) made formal application to the FDA OTC drug division that European phytomedicines be reviewed as old drugs based on their extensive usage in Europe. In 1993 and 1994 EAPC petitioned FDA to allow valerian to be reviewed in the night-time sleep aid category and ginger in the anti-nauseant category, respectively. (Blumenthal, 1995); Pinco & Israelsen, 1994; Pinco & Israelsen, 1995). FDA has not yet responded to these petitions.

The fourth regulatory category available for botanicals is via the IND/NDA (Investigational New Drug/New Drug Application) process, formerly the purview only of the U.S. pharmaceutical industry.

To date, according to sources within FDA's CDER (Center for Drug Evaluation and Research), there are 50 botanicals or botanical formulas holding active IND applications. Table 15 lists some of these products. Dr. Robert Temple, Director of the FDA Center for Drug Evaluation, has commented on this regulatory route for botanicals:

"A long history of safe use might provide sufficient safety information for products that are intended for short-term use. For something that's given only briefly...for short-term, you may consider the history of exposure, if it can be documented recently, as relevant safety. However, [it is still] questionable whether a history of safe use would be adequate to support the safety of an ingredient intended for regular, long-term use.

"FDA is willing to address clinical trials for traditional herbal products differently from drug trials....What we've proposed is that initial short-term controlled trials for materials marketed under DSHEA...would need little or no chemistry or toxicology data. The agency is attempting to reduce the obstacles to conducting clinical trials for herbal products.

"We don't have a rule that people who carry out trials have to be physicians. I don't see why someone with [an herbal] background couldn't carry out the trial. Someone who's experienced in [herbal] use, and believes that certain things are true is probably the best person to help design the trial. You can test Eastern philosophy in a Western controlled trial." (Temple, 1996.)

Prior to the passage of DSHEA, Loren Israelsen, Director of the Utah Natural Products Alliance, called the IND process for botanicals a "roach motel: easy to get in, but you never get out." (Israelson, 1998) Today, Mr. Israelsen feels that the IND process is still an obstacle course, but possible to surmount with the right product. Time will tell who is correct. Certainly the first botanical product to obtain prescription status will have tremendous effect on the industry. In response to this new regulatory channel, several divisions of FDA, under the direction of CDER, have developed a document for the development of botanical drugs. According to sources within FDA, this document, previously expected in November 1997, is due to be published in the fall of 1998.

The last category, as yet undeveloped, is that of a separate "traditional medicine" application for botanicals. This differentiation is accepted in many other parts of the world and endorsed as well by World Health Organization (WHO), which states:

"A guiding principle should be that if the product has been traditionally used without demonstrated harm no specific restrictive regulatory action should be undertaken unless new evidence demands a raised risk-benefit assessment. As a basic rule, documentation of a long period of use should be taken into consideration when safety is being assessed. This means that, when there are no detailed toxicological studies, documented experience on long term use without evidence of safety problems should form the basis of the risk assessment." (WHO, 1992)

Discussions within the industry and academia continue on the possible development of this new category.

CONSUMER ATTITUDES

One of the most important elements in understanding and developing the market for medicinal botanicals is current consumer attitudes. It is significant that Prevention Magazine, the Gallup Polls, New Hope Communication (publisher of several natural products industry magazines), and many individual companies (Celestial Seasonings, Warner Lambert, Leiner Health Products) have done extensive consumer polling in regards to acceptance and understanding of botanicals. Tables 16 and 17 show consumers' use of these products; Table 18 shows data on their safety. It is apparent that consumer survey data can vary widely depending on the questions asked, survey methodology, and sample population. The significance here is that the industry is now large enough to warrant investigation by major consumer survey companies.

STANDARDS PROJECTS

As the U.S. industry increases in sophistication for the use of these products, more demand for quality and standardization emerges. The American Botanical Council (ABC) has just published its translation of The Complete German Commission E Monographs -- Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. The European Scientific Cooperative on Phytomedicine (ESCOP) has developed 50 monographs on botanicals (Blumenthal, 1997). WHO now has 28 monographs in Volume I and another 30 monographs in preparation for Volume II (Phytopharm Consulting).

In the U.S., the American Herbal Pharmacopoeia has published an extensive monograph on St. John's wort (Upton, 1997) and hopes to publish six more monographs by early 1999. Two of these -- Hawthorn and Valerian -- are in completion stage. The other four nearing completion are: Astragalus, Schizandra, Willow, and Reishi.

The U.S. Pharmacopeia (USP) held its second conference on botanical standards this past August. The USP currently has prioritized 21 botanicals for monograph development (Table 19). Many botanicals were originally listed in the USP only to be discontinued because of lack of use.

The American Herbal Products Association (AHPA), the U.S. trade association for herbal product manufacturers, has published two important books. Herbs of Commerce is a listing of 600 of the most used botanicals, common name, and Latin binomial (Foster, 1992). This document has been cited by FDA in its regulations for implementation of DSHEA as the authoritative text for label nomenclature (21 CFR 101, 4(h)(2)). The second edition of this book will be available in late 1998, and will have over 1800 entries. AHPA has also published The Botanical Safety Handbook, a guide to use of botanical ingredients (McGuffin et al., 1997). It classifies the same 600+ botanicals into four categories, based on extensive literature review:

"Class 1 - Herbs which can be safely consumed when used appropriately.

Class 2 - Herbs for which the following use restrictions apply, unless otherwise directed by an expert qualified in the use of the described substance:

2a: For external use only

2b: Not to be used during pregnancy

2c: Not to be used while nursing

2d: Other specific use restrictions as noted

Class 3 - Herbs for which significant data exist to recommend the following labeling:

`To be used only under the supervision of an expert qualified in the appropriate use of this substance.' Labeling must include proper use information: dosage, contraindications, potential adverse effects and drug interactions, and any other relevant information related to the safe use of the substance.

Class 4 - Herbs for which insufficient data are available for classification." (McGuffin, et al., 1997) (See review in HerbalGram No. 40. pp. 59-60.)

Both publications, available from AHPA or the ABC Herbal Education Catalog (see Listing of Organizations, at the end of this article), delineate at least a portion of the list of herbs in commerce prior to October 15, 1994 -- the date by which any botanical must have been in commerce in order to gain "grandfather" status as acceptable as safe under DSHEA, and thus exempt from requirement to provide scientific evidence of its safety as "new dietary ingredients" under DSHEA.

Besides these publications, there are several analytical projects under way in the U.S. Most inclusive is the Methods Validation Program, the first project for the newly formed Institute for Nutriceutical Advancement (INA). INA is a noncorporate division of Industrial Laboratories of Denver, Colorado. This project has brought together over two dozen international herbal manufacturing and supplier companies to establish protocols for developing consensus on acceptable analytical procedures for botanicals in the marketplace.

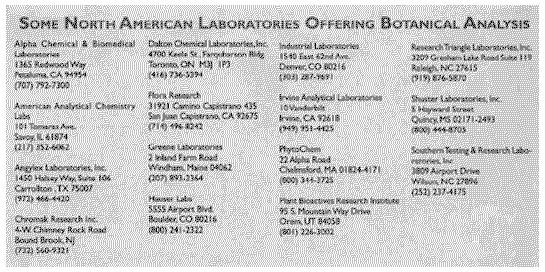

Two major issues facing the industry have been (1) the recognition that many botanicals today are standardized on marker rather than active chemical components, and (2) the need for standard methodology to analyze and identify these components in order to ensure a standardized and therefore batch-to-batch-replicable final product. Frequently, individual companies or labs have developed their own methods independently and therefore have not been able to do verification (third party) testing of procedures. This industry-wide effort should produce a set of protocols that can be accessed by any company to verify its procedures. Validated methods for the first three herbs, Ginkgo biloba, Echinacea spp., and Panax ginseng, are close to completion. The group has now begun work on the sourcing and validation of methods for kava and St. John's wort. See: Some North American Laboratories Offering Analysis of Botanical Products.

THE FUTURE

What does all this mean for the herb industry? Certainly as a new millennium approaches, there will be changes that will re-shape health care in the U.S. Assuming that this industry will continue to grow, here first is a look at some limits to its success.

- One of the greatest limiting factors is stress on future supply of raw material, St. John's wort and kava being two examples of demand exceeding supply. This is particularly true in the case of kava, which takes a minimum of 3-4 years to mature. The danger of adulteration can enter this picture if unscrupulous dealers try to quickly enter the market.

- This also leads to the issue of exploitation of indigenous people's knowledge of these medicines without appropriate compensation for both intellectual property rights ands ownership of the plant material itself.

Both publications, available from AHPA or the ABC Herbal Education Catalog (see Listing of Organizations, at the end of this article), delineate at least a portion of the list of herbs in commerce prior to October 15, 1994 -- the date by which any botanical must have been in commerce in order to gain "grandfather" status as acceptable as safe under DSHEA, and thus exempt from requirement to provide scientific evidence of its safety as "new dietary ingredients" under DSHEA.

Besides these publications, there are several analytical projects under way in the U.S. Most inclusive is the Methods Validation Program, the first project for the newly formed Institute for Nutriceutical Advancement (INA). INA is a noncorporate division of Industrial Laboratories of Denver, Colorado. This project has brought together over two dozen international herbal manufacturing and supplier companies to establish protocols for developing consensus on acceptable analytical procedures for botanicals in the marketplace.

Two major issues facing the industry have been (1) the recognition that many botanicals today are standardized on marker rather than active chemical components, and (2) the need for standard methodology to analyze and identify these components in order to ensure a standardized and therefore batch-to-batch-replicable final product. Frequently, individual companies or labs have developed their own methods independently and therefore have not been able to do verification (third party) testing of procedures. This industry-wide effort should produce a set of protocols that can be accessed by any company to verify its procedures. Validated methods for the first three herbs, Ginkgo biloba, Echinacea spp., and Panax ginseng, are close to completion. The group has now begun work on the sourcing and validation of methods for kava and St. John's wort. See: Some North American Laboratories Offering Analysis of Botanical Products.

THE FUTURE

What does all this mean for the herb industry? Certainly as a new millennium approaches, there will be changes that will re-shape health care in the U.S. Assuming that this industry will continue to grow, here first is a look at some limits to its success.

- One of the greatest limiting factors is stress on future supply of raw material, St. John's wort and kava being two examples of demand exceeding supply. This is particularly true in the case of kava, which takes a minimum of 3-4 years to mature. The danger of adulteration can enter this picture if unscrupulous dealers try to quickly enter the market.

- This also leads to the issue of exploitation of indigenous people's knowledge of these medicines without appropriate compensation for both intellectual property rights ands ownership of the plant material itself.

- Price considerations possibly overriding issues of quality result in low-cost ineffective products defining the market standard, and discouraging consumers from future purchases.

- Lack of herbal knowledge by new major players and the learning curve involved in order to discern quality material.

- Clinical trials designed without consideration of unique characteristics of botanicals (i.e., synergistic action, long-term effects, mild initial action, traditional use) as basis of design.

- Interactions between herbs and pharmaceutical drugs. More research needs to be conducted in this area. (Brinker, 1997)

- Industry is divided on whether the entry by major pharmaceutical companies into this category creates a positive or negative impact. Certainly this signifies a tremendous change in focus. Examples of this: American Home Products' alliance with PharmaPrint for a line of botanicals under the Centrum(R) brand, Bayer's summer 1998 introduction of botanical ingredients in their One-a-Day(R) line, Smith-Kline Beecham's introduction of their Abtei line from Germany, Warner Lambert's introduction of Quanterra single ingredient products, and several companies developing products that have yet to be launched.

Future trends may include:

- The growth (over 100 percent in spring of 1998) in the mass market (food, drug, mass merchandise) sector with botanical products indicates acceptance by the American consumer of these products.

- The increased emphasis on the need for U.S.-based clinical trials, including the recently formed Corporate Alliance For Integrative Medicine, composed of 10 major U.S. dietary supplement companies dedicated to supporting clinical work at major universities, as well as the NIH (National Institutes of Health) multi-site clinical trial on St. John's wort for mild depression, shows the increased market recognition for Western scientific validation of these products. It is interesting to note that the current big sellers in the U.S. (with the exception of goldenseal root) all had previous history as important products in the European market based on the results of clinical trials in Europe.

- With the partnering of American Home Products and PharmaPrint, and Paracelsian's development of its BioFIT(TM) "Functional Certification Program" method, interest in the industry has turned to bioassay validation of herbal ingredients. This is a complex issue, as understanding of the mechanisms by which a botanical functions in the human body cannot always be limited to a Western drug discovery model -- a model based on a single molecular entity and its ability to bind at a specific cellular receptor site.

- Price considerations possibly overriding issues of quality result in low-cost ineffective products defining the market standard, and discouraging consumers from future purchases.

- Lack of herbal knowledge by new major players and the learning curve involved in order to discern quality material.

- Clinical trials designed without consideration of unique characteristics of botanicals (i.e., synergistic action, long-term effects, mild initial action, traditional use) as basis of design.

- Interactions between herbs and pharmaceutical drugs. More research needs to be conducted in this area. (Brinker, 1997)

- Industry is divided on whether the entry by major pharmaceutical companies into this category creates a positive or negative impact. Certainly this signifies a tremendous change in focus. Examples of this: American Home Products' alliance with PharmaPrint for a line of botanicals under the Centrum(R) brand, Bayer's summer 1998 introduction of botanical ingredients in their One-a-Day(R) line, Smith-Kline Beecham's introduction of their Abtei line from Germany, Warner Lambert's introduction of Quanterra single ingredient products, and several companies developing products that have yet to be launched.

Future trends may include:

- The growth (over 100 percent in spring of 1998) in the mass market (food, drug, mass merchandise) sector with botanical products indicates acceptance by the American consumer of these products.

- The increased emphasis on the need for U.S.-based clinical trials, including the recently formed Corporate Alliance For Integrative Medicine, composed of 10 major U.S. dietary supplement companies dedicated to supporting clinical work at major universities, as well as the NIH (National Institutes of Health) multi-site clinical trial on St. John's wort for mild depression, shows the increased market recognition for Western scientific validation of these products. It is interesting to note that the current big sellers in the U.S. (with the exception of goldenseal root) all had previous history as important products in the European market based on the results of clinical trials in Europe.

- With the partnering of American Home Products and PharmaPrint, and Paracelsian's development of its BioFIT(TM) "Functional Certification Program" method, interest in the industry has turned to bioassay validation of herbal ingredients. This is a complex issue, as understanding of the mechanisms by which a botanical functions in the human body cannot always be limited to a Western drug discovery model -- a model based on a single molecular entity and its ability to bind at a specific cellular receptor site. - The synergy of the whole plant or the complex formula of several plants is probably the greatest challenge to the future of the industry.

- In addition, the entire concept of combination formula vs. individual herb (formula being the model already utilized in both Asian and traditional European herbal products) as the new paradigm for herbal products will create an arena for new products based on unique formulations. This leads to issues regarding patent possibilities for botanical products. In spite of the generally accepted statement, "herbs cannot be patented," there are, indeed, ways to look at patent protection. These include patents of:

- plant material whether it is bio-engineered or a unique cultivar

- processes of unique manufacturing techniques

- formulas for particular conditions

- dosage form

- unique release characteristics

- unique dosage regimen

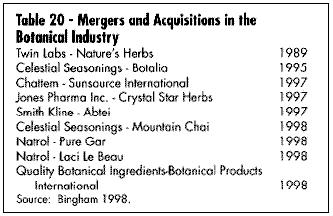

- The increasing consolidation within the industry at all levels of sales: retail, wholesale, and supply side (Table 20). This is a natural step in industry maturation.

- Lastly, the increasing interest by insurance companies and managed care organizations to reimburse the use of botanicals will probably be the key to their widespread use and acceptance. The American public still trusts their health care provider. Previously Americans have voted for these products with their pocketbooks. With increasing endorsement by the mainstream medical community and eventual insurance reimbursement, Americans will finally take their place with other industrialized nations in their acceptance of botanical medicines as part of their health care system.

Twenty-five years ago a few people asked for a future for this industry. Today this future is beginning to appear and we can say, "We are living in interesting times."

- The synergy of the whole plant or the complex formula of several plants is probably the greatest challenge to the future of the industry.

- In addition, the entire concept of combination formula vs. individual herb (formula being the model already utilized in both Asian and traditional European herbal products) as the new paradigm for herbal products will create an arena for new products based on unique formulations. This leads to issues regarding patent possibilities for botanical products. In spite of the generally accepted statement, "herbs cannot be patented," there are, indeed, ways to look at patent protection. These include patents of:

- plant material whether it is bio-engineered or a unique cultivar

- processes of unique manufacturing techniques

- formulas for particular conditions

- dosage form

- unique release characteristics

- unique dosage regimen

- The increasing consolidation within the industry at all levels of sales: retail, wholesale, and supply side (Table 20). This is a natural step in industry maturation.

- Lastly, the increasing interest by insurance companies and managed care organizations to reimburse the use of botanicals will probably be the key to their widespread use and acceptance. The American public still trusts their health care provider. Previously Americans have voted for these products with their pocketbooks. With increasing endorsement by the mainstream medical community and eventual insurance reimbursement, Americans will finally take their place with other industrialized nations in their acceptance of botanical medicines as part of their health care system.

Twenty-five years ago a few people asked for a future for this industry. Today this future is beginning to appear and we can say, "We are living in interesting times."

REFERENCES

Aarts T. Nutrition Business Journal. Personal communication. Sept. 1998.

ABC News/20-20. Using Herb's St. John's Wort to Treat Depression. June 27, 1997.

Akerele O. Summary of WHO Guidelines for the Assessment of Herbal Medicines. HerbalGram. 1993. 26: 13-20.

Anon. FDC Reports. The Tan Sheet. Jan. 5, 1998:10 Anon. FDC Reports. The Tan Sheet. May 4, 1998:22

Anon. FDC Reports. The Tan Sheet. June 15, 1998:19

Bannerman JE. Goldenseal in World Trade: Pressures and Potentials. HerbalGram. 1997; 41: 51-52.

Bingham R. Health Business Partners, Warwick, RI. Personal communication. September 23, 1998.

Blumenthal M. EAPC Files Petitions for OTC Drug Use for Valerian and Ginger. 1995. HerbalGram 1995, 35: 19-21, 63.

Blumenthal M. Herbal Monographs Initiated by Numerous Groups. HerbalGram. 1997; 40: 30-35, 37-38.

Blumenthal M, Busse WR, Goldberg A, Gruenwald J, Hall T, Riggins CW, Rister RS, (eds.) Klein S, Rister RS, (trans). The Complete German Commission E Monographs -- Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. Austin, TX: American Botanical Council; Boston, MA: Integrative Medicine Communications; 1998.

Brevoort P. The U.S. Herb Market An Overview. HerbalGram 1996; 36: 49-57.

Brevoort P, Doty D. East Earth Herb, Inc. September 1998.

Brinker F. Herb Contraindications and Drug Interactions. Eclectic Institute. 1997.

Code of Federal Regulations. 21CFR 101.4(h)(2). (Effective date, March 23, 1999.)

Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional Medicine in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328: 246-252.

Ferrier G. Nutrition Business Journal, San Diego, CA. Personal communication, September 1998.

Food and Drug Administration. O.T.C. Drug Review Ingredient Status Report. Sept. 1, 1994. Rockville, MD.

Food Label Use and Nutrition Education Survey (FLUNES Report) 1994. Center for Food Safety and Nutrition, FDA/CFSCAN. Washington, D.C.

Gallup Study of Attitudes Toward and Usage of Herbal Supplements, 1995, 1996, 1997.

Hartman & New Hope. Herb and Supplement Usage Nears 70 Percent. Natural Foods Merchandiser. 1998 Feb: 1.

Hartman & New Hope. Natural Foods Merchandiser, April 14, 1998.

Harris/Celestial Seasonings. Press release. April 14, 1998.

Heads Up, News Edge Corporation, Advertising Age 1998. July 20, p. 3. September 7, p. 4.

IRI, December 28, 1997.

IRI (Courtesy Pharmavite), Mission Hills, CA, July 1998.

Johnston BA. One-Third of Nation's Adults Use Herbal Remedies. HerbalGram. 1997; 40: 49.

Keating B. U.S. Tea is "Hot" Report, 3rd edition. Sage Group. Seattle, WA; 1997.

Kincheloe L. Herbal Medicines Can Reduce Costs in HMO. HerbalGram. 1997; 41: 49.

Kluger J. Mr. Natural. Time. May 12, 1997:68-75.

Leaders F, Ph.D. Personal communication. September 1, 1998.

Le Bars PL, Katz MM, Berman N, Itil TM, Freedman AM, Schatzberg AF. A Placebo-Controlled, Double-blind, Randomized Trial of an Extract of Ginkgo Biloba for Dementia. JAMA. 1997; 278(16): 1327-1332.

Linde K, Ramirez G, Mulrow CD, Pauls A, Weidenhammer W, Melchart D. St. John's wort for depression-an overview and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 1996; 313: 253-258.

McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, Goldberg A, editors. Introduction, American Herbal Products Association's Botanical Safety Handbook. CRC Press; 1997.

Murray F. "Vitamins 1- Drugs 100,000." Let's Live. 1996 Sep. 12.

Natural Foods Merchandiser, New Hope Communications, Boulder, CO. February 1998, June 1998.

Miller S. A Natural Mood Booster. Newsweek. 1997 May 5 74-75.

O.T.C. Update, Market Report Herbals. 1998 Jul; 98: 179.

Petersen A. The Making of an Herbal Superstar. Wall Street Journal. 1998 Feb 26: B1.

Pinco R., Israelsen L. European-American Phytomedicines Coalition; Citizen Petition to Amend FDA's Monograph on Antiemetic Drug Products for Over-the-Counter ("OTC") Human Use to Include Ginger. May 26, 1995.

Pinco R., Israelsen L. European-American Phytomedicines Coalition: Citizen Petition to Amend FDA's Monograph on Antiemetic Drug Products for Over-the-Counter ("OTC") Human Use to Include Valerian. June 7, 1994.

Pollock E, Moss M. Echinacea: Does it Cure What Ails Ya? Indians Thought So. Wall Street

Journal. Jan. 20, 1997: A1

Richman A, Witkowski JP. Herb Sales Still Strong. Whole Foods. 1998 Oct: 19-26.

Robbins CS. Medicinal Plant Conservation A Priority at TRAFFIC. HerbalGram. 1998;

44: 52-54.

Rosenthal L. Personal communication. Aug. 18, 1998.

Simone T, Simone and Associates, Lafayette, CA. Personal communication. October 1997.

SPINS, Spence Information Services, 185 Berry Street, Suite 5405, San Francisco, CA 94107 August 1998.

Srinivasan VS. U.S. Pharmacopeia, Rockville, MD. Personal communication. August 26, 1998.

Temple R, M.D. FDA Office of Drug Evaluation, DIA Annual Meeting. June 1996.

Towne-Oller. 1991-1997. Compiled by Peggy Brevoort.

Upton R, editor. American Herbal Pharmacopoeia. St. John's Wort Monograph. HerbalGram. 1997; 40 Suppl.: 1-32.

Article copyright American Botanical Council.

~~~~~~~~

By Peggy Brevoort

REFERENCES

Aarts T. Nutrition Business Journal. Personal communication. Sept. 1998.

ABC News/20-20. Using Herb's St. John's Wort to Treat Depression. June 27, 1997.

Akerele O. Summary of WHO Guidelines for the Assessment of Herbal Medicines. HerbalGram. 1993. 26: 13-20.

Anon. FDC Reports. The Tan Sheet. Jan. 5, 1998:10 Anon. FDC Reports. The Tan Sheet. May 4, 1998:22

Anon. FDC Reports. The Tan Sheet. June 15, 1998:19

Bannerman JE. Goldenseal in World Trade: Pressures and Potentials. HerbalGram. 1997; 41: 51-52.

Bingham R. Health Business Partners, Warwick, RI. Personal communication. September 23, 1998.

Blumenthal M. EAPC Files Petitions for OTC Drug Use for Valerian and Ginger. 1995. HerbalGram 1995, 35: 19-21, 63.

Blumenthal M. Herbal Monographs Initiated by Numerous Groups. HerbalGram. 1997; 40: 30-35, 37-38.

Blumenthal M, Busse WR, Goldberg A, Gruenwald J, Hall T, Riggins CW, Rister RS, (eds.) Klein S, Rister RS, (trans). The Complete German Commission E Monographs -- Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. Austin, TX: American Botanical Council; Boston, MA: Integrative Medicine Communications; 1998.

Brevoort P. The U.S. Herb Market An Overview. HerbalGram 1996; 36: 49-57.

Brevoort P, Doty D. East Earth Herb, Inc. September 1998.

Brinker F. Herb Contraindications and Drug Interactions. Eclectic Institute. 1997.

Code of Federal Regulations. 21CFR 101.4(h)(2). (Effective date, March 23, 1999.)

Eisenberg DM, Kessler RC, Foster C, et al. Unconventional Medicine in the United States. N Engl J Med. 1993; 328: 246-252.

Ferrier G. Nutrition Business Journal, San Diego, CA. Personal communication, September 1998.

Food and Drug Administration. O.T.C. Drug Review Ingredient Status Report. Sept. 1, 1994. Rockville, MD.

Food Label Use and Nutrition Education Survey (FLUNES Report) 1994. Center for Food Safety and Nutrition, FDA/CFSCAN. Washington, D.C.

Gallup Study of Attitudes Toward and Usage of Herbal Supplements, 1995, 1996, 1997.

Hartman & New Hope. Herb and Supplement Usage Nears 70 Percent. Natural Foods Merchandiser. 1998 Feb: 1.

Hartman & New Hope. Natural Foods Merchandiser, April 14, 1998.

Harris/Celestial Seasonings. Press release. April 14, 1998.

Heads Up, News Edge Corporation, Advertising Age 1998. July 20, p. 3. September 7, p. 4.

IRI, December 28, 1997.

IRI (Courtesy Pharmavite), Mission Hills, CA, July 1998.

Johnston BA. One-Third of Nation's Adults Use Herbal Remedies. HerbalGram. 1997; 40: 49.

Keating B. U.S. Tea is "Hot" Report, 3rd edition. Sage Group. Seattle, WA; 1997.

Kincheloe L. Herbal Medicines Can Reduce Costs in HMO. HerbalGram. 1997; 41: 49.

Kluger J. Mr. Natural. Time. May 12, 1997:68-75.

Leaders F, Ph.D. Personal communication. September 1, 1998.

Le Bars PL, Katz MM, Berman N, Itil TM, Freedman AM, Schatzberg AF. A Placebo-Controlled, Double-blind, Randomized Trial of an Extract of Ginkgo Biloba for Dementia. JAMA. 1997; 278(16): 1327-1332.

Linde K, Ramirez G, Mulrow CD, Pauls A, Weidenhammer W, Melchart D. St. John's wort for depression-an overview and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials. BMJ. 1996; 313: 253-258.

McGuffin M, Hobbs C, Upton R, Goldberg A, editors. Introduction, American Herbal Products Association's Botanical Safety Handbook. CRC Press; 1997.

Murray F. "Vitamins 1- Drugs 100,000." Let's Live. 1996 Sep. 12.

Natural Foods Merchandiser, New Hope Communications, Boulder, CO. February 1998, June 1998.

Miller S. A Natural Mood Booster. Newsweek. 1997 May 5 74-75.

O.T.C. Update, Market Report Herbals. 1998 Jul; 98: 179.

Petersen A. The Making of an Herbal Superstar. Wall Street Journal. 1998 Feb 26: B1.

Pinco R., Israelsen L. European-American Phytomedicines Coalition; Citizen Petition to Amend FDA's Monograph on Antiemetic Drug Products for Over-the-Counter ("OTC") Human Use to Include Ginger. May 26, 1995.

Pinco R., Israelsen L. European-American Phytomedicines Coalition: Citizen Petition to Amend FDA's Monograph on Antiemetic Drug Products for Over-the-Counter ("OTC") Human Use to Include Valerian. June 7, 1994.

Pollock E, Moss M. Echinacea: Does it Cure What Ails Ya? Indians Thought So. Wall Street

Journal. Jan. 20, 1997: A1

Richman A, Witkowski JP. Herb Sales Still Strong. Whole Foods. 1998 Oct: 19-26.

Robbins CS. Medicinal Plant Conservation A Priority at TRAFFIC. HerbalGram. 1998;

44: 52-54.

Rosenthal L. Personal communication. Aug. 18, 1998.

Simone T, Simone and Associates, Lafayette, CA. Personal communication. October 1997.

SPINS, Spence Information Services, 185 Berry Street, Suite 5405, San Francisco, CA 94107 August 1998.

Srinivasan VS. U.S. Pharmacopeia, Rockville, MD. Personal communication. August 26, 1998.

Temple R, M.D. FDA Office of Drug Evaluation, DIA Annual Meeting. June 1996.

Towne-Oller. 1991-1997. Compiled by Peggy Brevoort.

Upton R, editor. American Herbal Pharmacopoeia. St. John's Wort Monograph. HerbalGram. 1997; 40 Suppl.: 1-32.

Article copyright American Botanical Council.

~~~~~~~~

By Peggy Brevoort

|