Issue: 68 Page: 34-48

India's Foundation for the Revitalization of Local Health Traditions

by N. Mohan Karnat, Sarah K. Khan, Darshan Shankar

HerbalGram. 2005; 68:34-48 American Botanical Council

India’s Foundation for the Revitalization of Local Health Traditions

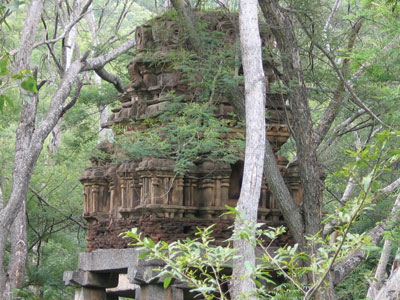

Ancient temple located in the Medicinal Plant Conservation Area at Savandurga, Karnataka. Photo ©2004 Sarah Khan.

India’s Foundation for the Revitalization of Local Health

Traditions

Pioneering In Situ

Conservation Strategies for Medicinal Plants and Local Cultures

by Sarah K. Khan, N. Mohan Karnat, and Darshan Shankar

As medicinal plant use has become more popular

worldwide, concern about plant conservation and sustainability has increased. According to the

Medicinal Plant Specialist Group of the International Union for the

Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), more than 20,000 plant

species are used medicinally worldwide. Nearly half of these species are

potentially threatened by either over-harvest or loss of habitat.1

Biological diversity includes a wide spectrum of types and

levels of biological variation. This spectrum ranges from genetic variability

within a species, to the plant life of some selected region in the world, to

the number of evolutionary lineages and the distinctness among them, to the

diversity of ecosystems and biomes on the earth.2 Southwest American

native culture and botanical expert Gary P. Nabhan argues that most

biodiversity on Earth today occurs in areas where cultural diversity also

persists.3 This principle is also recognized in the Declaration of

Belem produced at the International Congress of Ethnobiology in Belem, Brazil,

in 1988.4 Nabhan states that 60% of the world’s remaining 6,500

languages are spoken in 9 countries. Of the 9 countries, 6 of them are centers

of mega-diversity for flora and fauna: Mexico, Brazil, Indonesia, India, Zaire,

and Australia. In short, where many cultures have coexisted within the same

region, biodiversity has also survived.3

India is among the most important countries regarding

ancient healing traditions. Its rich array of medicinal plants is used both in

commerce and by local populations. Unfortunately, only a small percentage of

these medicinal plants are cultivated. The rest are often destructively

collected from the wild with little attention to conservation. This short-term

plant collection strategy poses a serious threat to the viability of already

threatened Indian medicinal plant species. One leading scientist in the field

of medicinal plant conservation, Peter Raven, PhD, Director of the Missouri

Botanical Garden, concludes that in situ (natural habitat) conservation of

medicinal plants is the conservation method of choice.5

India has responded with a solution that may serve as a

model for other countries. The Foundation for the Revitalization of Local

Health Traditions (FRLHT), founded and directed by the third author of this

paper (Darshan Shankar), is engaged in the field of in situ conservation of

India’s medicinal plants with a multi-faceted, innovative approach. Against the

backdrop of increasing world attention on the need for sustainability of

medicinal plants, the authors present the story of FRLHT’s pioneering in situ

conservation project to promote the future of India’s rich biodiversity.

Rishi grinding/preparing herbs at the Medicinal Plant Conservation Area entrance. Photo ©2004 Sarah Khan.

Chiang Mai and Bangalore Declarations

In March 1988 in Chiang Mai, Thailand, the World Health

Organization (WHO), the IUCN, World Conservation Union (WCU), and World Wide

Fund for Nature (WWF) convened the First International Consultation on the

Conservation of Medicinal Plants. They produced a set of conservation

guidelines and a consensus statement—“Saving Lives by Saving Plants” —known as

the Chiang Mai Declaration.6

Ten years later in February 1998, a larger coalition of

agencies organized the Second International Consultation on Medicinal Plants in

Bangalore, India. This group produced the Bangalore Declaration (participants

listed in Table 1 on page 42).7 In the Bangalore Declaration, the

coalition affirmed the use of medicinal plants in primary healthcare since 80%

of the population in developing countries depends on plant medicines.8

The coalition also expressed concern about the following challenges to

sustaining biodiversity:

(1) Loss

of plant biodiversity and its consequences,

(2) Threat

of habitat destruction and non-sustainable harvest practices to medicinal plant

conservation,

(3) Loss

of potential new drugs,

(4) Loss

of indigenous cultures, and

(5) Urgent

need for international cooperation in this field.

Furthermore, the coalition identified priorities for the

conservation and sustainable utilization of medicinal plants. These priorities

included the following guidelines:

(1) Increase

ethnobotanical studies that identify and inventory medicinal plants and their

traditional uses;

(2) Promote

the sustainable utilization of medicinal plants through cultivation, regulated

harvest from the wild, and verification of sustainable harvesting methods;

(3) Increase

both in situ (natural habitat) and ex situ (artificial

habitat) conservation of medicinal plants; and

(4) Increase

public support for conservation of medicinal plants through communication,

education, and cooperation.9

| Table 1. Participants in the Second International Consultation on Medicinal Plants in Bangalore, India (1998) |

| ATREE |

Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment, India |

| BCN |

Biodiversity Conservation Network, Philippines |

| BGCI |

Botanical Gardens Conservation International, UK |

| FAO |

Food and Agricultural Organization, Rome, Italy |

| FRLHT |

Foundation for the Revitalization of Local Health Traditions, India |

| GIFTS |

Global Initiative for Traditional Systems of Health, Oxford, UK |

| ICIMOD |

International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development, Nepal |

| IDRC |

International Development Research Centre, UK |

| IISc |

Indian Institute of Science, India |

| IUCN |

International Union for the Conservation of Nature |

| MPSG |

Medicinal Plants Specialist Group |

| MSSRF |

MS Swaminathan Research Foundation, India |

| RHRC |

Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Columbia University,

NY, USA |

| WWF |

World Wide Fund, UK |

Left: FRLHT entrance, Bangalore, Karnataka. Right: FRLHT dried plant specimens ready for testing. Photos ©2004 Sarah Khan.

An Unconventional Indian Educational Institution

Located in the south Indian city of Bangalore in the state

of Karnataka, FRLHT promotes the conservation of Indian medicinal plant

diversity in collaboration with state forest departments (SFDs), environmental

non-governmental organizations (NGOs), research institutions, and local

communities. As an unconventional educational institution, FRLHT engages in

many activities to promote diversity of plants and cultures, but its main

pioneering effort is the establishment of the world’s first in situ gene bank

network of 55 conservation sites. The focus of these in situ sites is the

conservation of wild medicinal plant germplasm (seed) resources.

FRLHT has a multi-disciplinary staff drawn from forestry,

botany, agriculture, ecology, chemistry, traditional medicine, management,

media, and computer science. The mission of FRLHT is 3-fold: (1) conserving and

sustaining the utilization of medicinal plants, which includes promoting

medicinal plant enterprises for income generation and employment in rural

communities; (2) strengthening local health traditions in rural and urban

communities; and (3) promoting research on medical, sociological, and

epistemological aspects of the Indian medical heritage.

Left: FRLHT grounds. Right: FRLHT plant specimens in storage. Photos ©2004 Sarah Khan.

FRLHT has also participated in a form of research called

“action research.” By implementing projects of scale and size that have a

social impact, FRLHT members gain first-hand experience in the field. The

foundation focuses on in situ and ex situ medicinal plant conservation. In the

ex situ program, FRLHT demonstrates at a taluka (district) level how local institutions create community conservation

educational centers that serve as a repository for the region’s medicinal plant

resources and local health knowledge. For the first time in India, FRLHT has

assessed the status of threatened medicinal plants based on the IUCN’s criteria

for categorizing the “red-listed” plants. (See Table 2 on page 43 for IUCN red

list categories and definitions; see Table 3 on page 45 for red-listed

medicinal plants). These threat assessments have assigned global red-list

status for species endemic to the region. With respect to non-endemic species,

the assessments reflect local concerns about the depletion of their wild

populations and do not necessarily reflect the risk of extinction for

individual plant taxa. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species is a

comprehensive inventory of the global conservation status for plant and animal

species. Using a set of strong scientific criteria to evaluate the extinction

risk of thousands of species and subspecies, the IUCN Red List is recognized as

the most authoritative guide to the status of biological diversity at the

species level and below. The taxa assessed for the IUCN Red List represent the

genetic diversity and ecosystem building blocks. The overall aim of the IUCN

Red List is to convey the urgency and scale of conservation problems to the

public and policymakers, and to motivate the global community to help reduce

species extinctions.10

| Table 2: Definitions of the Red List Categories according to IUCN |

Extinct (EX)

A taxon is Extinct when there is no reasonable doubt that the last individual has died. A taxon is presumed Extinct when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. Surveys should be over a time frame appropriate to the taxon’s life cycle and life form.

Extinct in the Wild (EW)

A taxon is Extinct in the Wild when it is known only to survive in cultivation, in captivity, or as a naturalized population (or populations) well outside the past range. A taxon is presumed Extinct in the Wild when exhaustive surveys in known and/or expected habitat, at appropriate times (diurnal, seasonal, annual), throughout its historic range have failed to record an individual. Surveys should be over a time frame appropriate to the taxon’s life cycle and life form.

Critically Endangered (CR)

A taxon is Critically Endangered when the best available evidence indicates that it meets any of criteria A to E for Critically Endangered (see the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria booklet for details at http://www.redlist.org/info/categories_criteria.html). It is therefore considered to be facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild.

Endangered (EN)

A taxon is Endangered when the best available evidence indicates that it meets any of criteria A to E for Endangered (see the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria booklet for details.) It is therefore considered to be facing a very high risk of extinction in the wild.

Vulnerable (VU)

A taxon is Vulnerable when the best available evidence indicates that it meets any of the criteria A to E for Vulnerable (see the IUCN Red List Categories and Criteria booklet for details.) It is therefore considered to be facing a high risk of extinction in the wild.

Near Threatened (NT)

A taxon is Near Threatened when it has been evaluated against the criteria but does not currently qualify for Critically Endangered, Endangered, or Vulnerable, but is close to qualifying or is likely to qualify for a threatened category in the near future.

Least Concern (LC)

A taxon is Least Concern when it has been evaluated against the criteria and does not qualify for Critically Endangered, Endangered, Vulnerable, or Near Threatened. Widespread and abundant taxa are included in this category.

Data Deficient (DD)

A taxon is Data Deficient when there is inadequate information to make a direct or indirect assessment of its risk of extinction based on its distribution and/or population status. A taxon in this category may be well studied and its biology well known, but appropriate data on abundance and/or distribution are lacking. Data Deficient is therefore not a category of threat. Listing of taxa in this category indicates that more information is required and acknowledges the possibility that future research will show that threatened classification is appropriate. It is important to make positive use of whatever data are available. In many cases great care should be exercised in choosing between DD and a threatened status. If the range of a taxon is suspected to be relatively circumscribed, and a considerable period of time has elapsed since the last record of the taxon, threatened status may well be justified.

Not Evaluated (NE)

A taxon is Not Evaluated when it is has not yet been evaluated against the criteria. |

| Source: 2004 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available at: http://www.redlist.org. Accessed June 17, 2005. |

FRLHT has created computerized databases on the botany,

distribution, agriculture, trade aspects, and indigenous knowledge of Indian

medicinal plants. (For more details, see the sidebar on page 38 “FRLHT Efforts

go Beyond Conservation.” The botanical and vernacular nomenclature,

distribution, and threat status are available on the FRLHT Web site at

http://envis.frlht.org.in/).

Table 3. Threatened Medicinal Plants in Southern India*†

Part A: Endemic Medicinal Plants |

| Latin Binomial, Authority & Family |

Global Status |

| Adhatoda beddomei C. B. Clarke (Acanthaceae) |

CR |

| Aerva wightii Hook.f. (Acanthaceae) |

EX |

| Amorphophallus commutatus (Schott) Engl.(Araceae) |

VU |

| Ampelocissus araneosa (Dalz. & Gibson) Planch.(Vitaceae) |

VU |

| Artocarpus hirsutus Lam. (Moraceae) |

VU |

| Asparagus rottleri Baker (Lilliaceae) |

EX |

| Calophyllum apetalum Willd. (Guttiferae) |

VU |

| Cayratia pedata (Lam.) Juss. var. glabra Gamble (Vitaceae) |

EN |

| Cinnamomum macrocarpum Hook.f (Lauraceae). |

VU |

| Cinnamomum sulphuratum Nees (Lauraceae) |

VU |

| Cinnamomum wightii Meisn. (Lauraceae) |

EN |

| Curcuma pseudomontana Grah. (Zingiberaceae) |

VU |

| Decalepis hamiltonii Wight & Arn. (Asclepiadaceae) |

EN |

| Diospyros candolleana Wight (Ebenaceae) |

VU |

| Diospyros paniculata Dalz. (Ebenaceae) |

VU |

| Dipterocarpus indicus Bedd. (Dipterocarpaceae) |

EN |

| Dysoxylum malabaricum Bedd. ex Hiern (Meliaceae) |

EN |

| Eulophia cullenii (Wight) Blume (Orchidaceae) |

CR |

| Eulophia ramentacea Wight (Orchidaceae) |

DD |

| Garcinia gummi-gutta (L.) Robson (Clusiaceae) |

LRnt |

| Garcinia indica (Thouars) Choisy (Clusiaceae) |

VU |

| Garcinia travancorica Bedd. (Clusiaceae) |

EN |

| Gardenia gummifera L.f. (Rubiaceae) |

VU |

| Glycosmis macrocarpa Wight (Rutaceae) |

VU |

| Gymnema khandalense Santapau (Asclepiadaceae) |

EN |

| Gymnema montanum (Roxb.) Hook.f. (Asclepiadaceae) |

EN |

| Heliotropium keralense Sivar. & Manilal (Boraginaceae) |

CR |

| Heracleum candolleanum (Wight & Arn.) Gamble (Apiaceae) |

VU |

| Humboldtia vahliana Wight (Orchidadeae) |

EN |

| Hydnocarpus alpina Wight (Flacourtiaceae) |

VU |

| Hydnocarpus macrocarpa (Bedd.) Warb. (Flacourtiaceae) |

EN |

| Hydnocarpus pentandra (Buch.-Ham.) Oken (Flacourtiaceae) |

VU |

| Janakia arayalpathra J. Joseph & V. Chandras. (Periplocaceae) |

CR |

| Kingiodendron pinnatum (Roxb. ex DC.) Harms (Fabaceae) |

VU |

| Knema attenuata (Hook.f. & Thoms.) Warb. (Myristicaceae) |

LRnt |

| Lamprachaenium microcephalum Benth. (Asteraceae) |

DD |

| Madhuca diplostemon (C.B.Clarke) Royen (Sapotaceae) |

DD |

| Madhuca insignis (Radlk.) H.J.Lam (Sapotaceae) |

EX |

| Michelia nilagirica Zenk. (Magnoliaceae) |

VU |

| Myristica malabarica Lam. (Myristaceae) |

VU |

| Nilgirianthus ciliatus (Nees) Bremek. (Acanthaceae) |

EN |

| Ochreinauclea missionis (Wall. ex G. Don) Ridsdale (Rubiaceae) |

VU |

| Paphiopedilum druryi (Bedd.) Pfitz. (Orchidaceae) |

CR |

| Piper barberi Gamble (Piperaceae) |

CR |

| Plectranthus nilgherricus Benth. (Lamiaceae) |

EN |

| Pterocarpus santalinus L.f. (Fabaceae) |

EN |

| Semecarpus travancorica Bedd. (Anacardiaceae) |

EN |

| Shorea tumbuggaia Roxb. (Dipterocarpaceae) |

CR |

| Strychnos aenea A. W. Hill (Strychnaceae) |

EN |

| Swertia corymbosa (Griseb.) Wight ex C.B.Clarke (Gentianaceae) |

VU |

| Swertia lawii (C.B.Clarke) Burkill (Gentianaceae) |

EN |

| Syzygium travancoricum Gamble (Myrtaceae) |

CR |

| Tragia bicolor Miq. (Euphorbiaceae) |

VU |

| Trichopus zeylanicus Gaertn.subsp. travancoricus (Bedd.) Burkill (Trichopodaceae) |

EN |

| Utleria salicifolia Bedd.(Periplocaceae) |

CR |

| Valeriana leschenaultii DC. (Valerianaceae) |

CR |

| Vateria indica L (Dipterocarpaceae) |

VU |

| Vateria macrocarpa B. L. Gupta (Dipterocarpaceae) |

CR |

* Plants are categorized according to the IUCN Red List criteria.

† Also see Table E1 Threatened Medicinal Plants in North India and Table E2 Threatened High-Altitude Medicinal Plants of the North-West Himalayas below.

Key: EX = Extinct; EW = Extinct in the wild; CR = Critically endangered; EN = Endangered; VU = Vulnerable; LRNT = Lower risk, Near threatened; LRLC = Lower risk, least concern; DD = Data deficient; NE = Not evaluated

Source: Data compiled based on 4 Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) Workshops. |

Table 3. Threatened Medicinal Plants in Southern India

Part B: Non-Endemic Medicinal Plants |

| Botanical Name |

Regional Status |

| Karnataka |

Kerala |

Tamil Nadu |

| Acorus calamus L. (Acoraceae) |

DD |

EN |

VU |

| Adenia hondala (Gaertn.) Wilde (Passifloraceae) |

VU |

VU |

EN |

| Aegle marmelos (L.) Corr. (Rutaceae) |

VU |

NE |

VU |

| Amorphophallus paeoniifolius (Dennst.) Nicolson (Araceae) |

DD |

LRnt |

VU |

| Ampelocissus indica (L.) Planch. (Vitaceae) |

EN |

EN |

EN |

| Aphanamixis polystachya (Wall.) Parker (Meliaceae) |

VU |

VU |

DD |

| Aristolochia tagala Cham (Aristolochiaceae) |

VU |

LRlc |

DD |

| Baliospermum montanum (Willd.) Mull.Arg.(Euphorbiaceae) |

VU |

VU |

DD |

| Canarium strictum Roxb. (Burseraceae) |

VU |

VU |

VU |

| Celastrus paniculatus Willd. (Celastraceae) |

LRnt |

VU |

LRnt |

| Chonemorpha fragrans (Moon) Alston (Apocynaceae) |

EN |

VU |

DD |

| Commiphora wightii (Arn.) Bhandari (Buseraceae) |

NE |

NE |

NE |

| Coscinium fenestratum (Gaertn.) Coleb. (Minispermaceae) |

CR |

CR |

CR |

| Cycas circinalis L. (Cycadaceae) |

CR |

VU |

CR |

| Drosera indica L. (Droseraceae) |

EN |

LRlc |

LRlc |

| Drosera peltata J.E.Sm. ex Willd. (Droseraceae) |

EN |

VU |

EN |

| Embelia ribes Burm.f. (Myrsinaceae) |

VU |

LRnt |

VU |

| Embelia tsjeriam-cottam (Roem. & Schult.) DC. (Myrsinaceae) |

VU |

VU |

VU |

| Garcinia morella (Gaertn.) Desr. (Clusiaceae) |

VU |

LRnt |

VU |

| Gloriosa superba L. (Colchicaceae) |

VU |

VU |

LRlc |

| Hedychium coronarium Koenig (Zingiberaceae) |

LRnt |

LRnt |

LRlc |

| Helminthostachys zeylanica (L.) Hook. (Ophioglossaceae) |

DD |

VU |

CR |

| Holostemma ada-kodien Schultes (asclepiadaceae) |

VU |

EN |

LRnt |

| Kaempferia galanga L. (Zingiberaceae) |

NE |

NE |

NE |

| Madhuca longifolia (Koen.) Macbr. (Sapotaceae) |

VU |

NE |

LRlc |

| Madhuca neriifolia (Moon) H.J.Lam (Sapotaceae) |

VU |

LRlc |

LRlc |

| Michelia champaca L. (Magnoliaceae) |

EN |

LRnt |

VU |

| Moringa concanensis Nimmo ex Dalz. & Gibson (Moringaceae) |

NE |

NE |

LRlc |

| Myristica dactyloides Gaertner (Myristicaceae) |

VU |

VU |

LRlc |

| Nervilia aragoana Gaud. (Orchidaceae) |

LRnt |

VU |

EN |

| Nothapodytes nimmoniana (Graham) Mabber. (Icacinaceae) |

EN |

VU |

VU |

| Operculina turpethum (L.) Silva Manso (Convolvulaceae) |

VU |

EN |

LRnt |

| Oroxylum indicum (L.) Benth. ex Kurz (Bignoniaceae |

VU |

EN |

DD |

| Persea macrantha (Nees) Kosterm. (Lauraceae) |

EN |

VU |

EN |

| Piper longum L. (Piperaceae) |

NE |

LRnt |

EN |

| Piper mullesua Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don (Piperaceae) |

CR |

LRnt |

VU |

| Piper nigrum L. (Piperaceae) |

LRnt |

LRlc |

LRnt |

| Plectranthus vettiveroides (Jacob) Singh & Sharma (Lamiaceae) |

NE |

NE |

CR |

| Pseudarthria viscida (L.) Wight & Arn. (Fabaceae) |

VU |

VU |

LRnt |

| Pueraria tuberosa (Roxb. ex Willd.) DC. (Fabaceae) |

CR |

NE |

VU |

| Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Benth. ex Kurz (Apocynaceae) |

EN |

EN |

EN |

| Rhaphidophora pertusa (Roxb.) Schott (Araceae) |

VU |

LRlc |

LRnt |

| Salacia oblonga Wall. ex Wight & Arn. (Celastraceae) |

CR |

EN |

LRnt |

| Salacia reticulata Wight (Celastraceae) |

CR |

DD |

NE |

| Santalum album L. (Santalaceae) |

VU |

EN |

EN |

| Saraca asoca (Roxb.) Wilde (Caesalpiniaceae) |

EN |

DD |

DD |

| Schrebera swietenioides Roxb. (Oleaceae) DD |

VU |

NE |

DD |

| Smilax zeylanica L. (Smilacaceae) |

LRnt |

VU |

LRlc |

| Symplocos cochinchinensis (Lour.) Moore ssp. laurina (Retz.) Nooteb (Symplocaceae) |

LRnt |

LRlc |

LRlc |

| Symplocos racemosa Roxb. (Symplocaceae) |

VU |

DD |

LRnt |

| Terminalia arjuna (Roxb. ex DC.) Wight & Arn. (Combretaceae) |

LRnt |

LRnt |

LRlc |

| Tinospora sinensis (Lour.) Merr. (Menispermaceae) |

VU |

LRnt |

NE |

Key: EX = Extinct; EW = Extinct in the wild; CR = Critically endangered; EN = Endangered; VU = Vulnerable; LRNT = Lower risk, Near threatened; LRLC = Lower risk, least concern; DD = Data deficient; NE = Not evaluated

Source: Data compiled based on 4 Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) Workshops. |

| Table E1. Threatened Medicinal Plants in North India* |

| Latin Binomial, Authority & Family |

North India Region |

| Critical |

| Aconitum balfourii Stapf (Ranunculaceae) |

Northwest |

| Aconitum deinorrhizum Stapf (Ranunculaceae) |

Northwest |

| Aconitum falconeri Stapf (Ranunculaceae) |

Northwest |

| Aconitum ferox Wall. (Ranunculaceae) |

Northwest |

| Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. (Ranunculaceae) |

Northwest |

| Aconitum violaceum Jacquem. ex Stapf (Ranunculaceae) |

Northwest |

| Acorus calamus L. (Acoraceae) |

Northeast |

| Angelica glauca Edgew. (Apiaceae) |

Northwest |

| Aquilaria malaccensis Benth. (Thymelaeaceae) |

Northeast |

| Arnebia benthami (Wall. ex G.Don) Johnst. (Boraginaceae) |

Northwest |

| Atropa acuminata Royle. (Solanaceae) |

Northwest |

| Berberis kashmirana Ahrendt. (Berberidaceae) |

Northwest |

| Craterostigma plantagineum Hochst. (Scrophulariaceae) |

Central |

| Curcuma caesia Roxb. (Zingiberaceae) |

Central |

| Dactylorhiza hatagirea (D.Don) Soo (Orchidaceae) |

Northwest |

| Delphinium denudatum Wall. (Ranunculaceae) |

Northwest |

| Dioscorea deltoidea Wall. (Dioscoreaceae) |

Northwest |

| Fritillaria roylei Hook. (Liliaceae) |

Northwest |

| Gentiana kurroo Royle (Gentianaceae) |

Northwest |

| Inula racemosa Hook.f. (Asteraceae) |

Northwest |

| Ilex khasiana Purkay. (Aquifoliaceae) |

Northwest |

| Luvunga scandens Thwaites (Rutaceae) |

Northeast |

| Meconopsis aculeata Royle (Papaveraceae) |

Northeast |

| Nardostachys jatamansi DC. (Valerianaceae) |

Northwest |

| Nepenthes khasiana Hook.f. (Nepenthaceae) |

Northeast |

| Podophyllum hexandrum Royle (Berberidaceae) |

Northeast & Northwest |

| Przewalskia tangutica Maxim. (Solanaceae) |

Northeast |

| Saussurea costus (Falc.) Lipsch. (Asteraceae) |

Northwest |

| Taxus wallichiana Zucc. (Taxaceae) |

Northeast |

| Valeriana jatamansi Wall. (Valerianaceae) |

Northeast |

| Endangered |

| Berberis aristata DC. (Berberidaceae) |

Northwest |

| Berberis lycium Royle (Berberidaceae) |

Northwest |

| Bunium persicum B.Fedtsch. (Apiaceae) |

Northwest |

| Gastrochilus longiflora Wall. (Zingiberaceae) |

Northeast |

| Gloriosa superba L. (Euphorbiaceae) |

Central |

| Heracleum candicans Wall. ex DC. (Apiaceae) |

Northwest |

| Hydnocarpus kurzii Warb. (Flacourtiaceae) |

Northeast |

| Hedychium coronarium Koen. (Scitamineae) |

Central |

| Lavatera kashmiriana Mast. (Malvaceae) |

Northwest |

| Panax pseudoginseng Wall. var. Notoginseng (Burkill) G. Hoo & C.J. Tseng (Araliaceae) |

Northeast |

| Picrorhiza kurroa Royle ex Benth. (Scrophulariaceae) |

Northeast & Northwest |

| Polygonatum verticillatum All. (Liliaceae) |

Northwest |

| Rauvolfia serpentina (L.) Kurz (Apocynaceae) |

Central |

| Rheum nobile Hook.f. & Thomson (Polygonaceae) |

Northeast |

| Saussurea gossypiphora Wall. (Asteraceae) |

Northwest |

| Saussurea obvallata Wall. (Asteraceae) |

Northwest |

| Saussurea simpsoniana (Field. & Gardn.) Lipsch. Asteraceae |

Northwest |

| Swertia angustifolia Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don (Gentianaceae) |

Central |

| Vulnerable |

| Berberis chitria D.Don (Berberidaceae) |

Northwest |

| Bergenia ligulata (Wall.) Engl. (Saxifragaceae) |

Northwest |

| Clerodendrum colebrookianum Walp. (Verbenaceae) |

Northeast |

| Clerodendrum serratum (Linn.) Moon (Verbenaceae) |

Central |

| Coptis teeta Wall. (Ranunculaceae) |

Northeast |

| Curculigo orchioides Gaertn. (Hypoxidaceae) |

Central |

| Curcuma angustifolia Roxb. (Zingiberaceae) |

Central |

| Gymnema sylvestre (Retz.) Schult. (Asclepiadaceae) |

Central |

| Hedychium spicatum Lodd. (Zingiberaceae) |

Northwest |

| Ipomoea turpethum (L.) R.Br. (Convolvulaceae) |

Central |

| Paeonia emodi Royle (Paeoniaceae) |

Northwest |

| Rheum australe D.Don (Polygonaceae) |

Northwest |

| Rhododendron anthopogon D.Don (Ericaceae) |

Northeast |

| Rhus semialata Murr. (Anacardiaceae) |

Northeast |

| Thalictrum foliolosum DC. (Ranunculaceae) |

Northwest |

| Tylophora indica Merr. (Asclepiadaceae) |

Central |

| Urginea indica Kunth (Hyacinthaceae) |

Central |

| Low Risk, Near Threatened |

| Baliospermum montanum Mull.Arg. (Euphorbiaceae) |

Central |

| Celastrus paniculatus Willd. (Celastraceae) |

Central |

| Cinnamomum tamala T.Nees & Eberm. (Lauraceae) |

Northwest |

| Cordia rothii Roem. & Schult. (Boraginaceae) |

Central |

| Jurinea dolomiaea Boiss. (Asteraceae) |

Northwest |

| Low Risk, Least Concern |

| Evolvulus alsinodes Kuntze (Convolvulaceae) |

Central |

* Plants are categorized according to the IUCN Red List Criteria as part of the Biodiversity Conservation Prioritization Project.

Source: Data assessed by a Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (CAMP) Workshop Process WWF, India, ZOO/CBSG, India, U.P. Forest Department January 21-25, 1997, Kukrail Park, Lucknow, India. |

| Table E2. Threatened High-Altitude Medicinal Plants Of The North-West Himalayas* |

Jammu & Kashmir Regions |

| Critically Endangered |

| Aconitum chasmanthum Stapf ex Holmes (Ranunculaceae) |

| Arnebia benthami (Wall. ex G.Don) I.M.Johnst. (Boraginaceae) |

| Dactylorhiza hatagirea (D.Don) Soo (Orchidaceae) |

| Fritillaria roylei Hook. (Liliaceae) |

| Gentiana kurroo Royle (Gentianaceae) |

| Saussurea costus (Falc.) Lipsch Compositae |

| Endangered |

| Aconitum deinorrhizum Stapf (Ranunculaceae) |

| Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. ex Royle (Ranunculaceae) |

| Angelica glauca Edgew. (Apiaceae ) |

| Arnebia euchroma (Royle) I.M.Johnst. (Boraginaceae) |

| Artemisia maritima L. (Asteraceae) |

| Betula utilis D.Don (Betulaceae) |

| Ephedra gerardiana Wall. (Ephedraceae) |

| Jurinea dolomiaea Boiss. (Asteraceae) |

| Meconopsis aculeata Royle (Papaveraceae) |

| Picrorhiza kurrooa Royle ex Benth. (Scrophulariaceae) |

| Podophyllum hexandrum Royle (Berberidaceae) |

| Vulnerable |

| Aconitum violaceum Jacq. ex Stapf (Ranunculaceae) |

| Allium stracheyi Baker (Alliaceae) |

| Bergenia stracheyi (Hook.f. & Thoms.) Engl. (Saxifragaceae) |

| Ferula jaeschkeana Vatke (Apiaceae) |

| Heracleum lanatum Michx. (Apiaceae) |

| Malaxis muscifera (Lindley) Kuntze (Orchidaceae) |

| Physochlaina praealta (Walp.) Miers (Solanaceae) |

| Polygonatum multiflorum (L.) All. (Liliaceae) |

| Polygonatum verticillatum (L.) All. (Liliaceae) |

| Rheum australe D. Don (Polygonaceae) |

| Rheum moorcroftianum Royle (Polygonaceae) |

| Rheum spiciforme Royle (Polygonaceae) |

| Rheum webbiana Royle (Polygonaceae) |

| Rhododendron lepidotum Wall. ex D. Don (Ericaceae) |

| Saussurea gossypiphora D.Don (Asteraceae) |

| Saussurea obvallata (DC.) Edgew. Asteraceae |

| Lower Risk -- Near Threatened |

| Hippophae rhamnoides L. (Elaeagnaceae) |

| Hyoscyamus niger L. (Solanaceae) |

| Lower Risk -- Least Concern |

| Selinum tenuifolium Wall. ex DC. Apiaceae |

| Selinum vaginatum (Edgew.) C.B. Clarke Apiaceae |

| Data Deficient |

| Ferula narthex Boiss. (Apiaceae) |

| Not Evaluated |

| Inula racemosa Hook.f. (Asteraceae) |

| Nardostachys grandiflora DC. (Valerianaceae) |

Himachal Pradesh Region |

| Critically Endangered |

| Arnebia benthami (Wall. ex G.Don) Johnst. (Boraginaceae) |

| Dactylorhiza hatagirea (D.Don) Soo (Orchidaceae) |

| Endangered |

| Aconitum deinorrhizum Stapf (Ranunculaceae) |

| Aconitum heterophyllum Wall. ex Royle (Ranunculaceae) |

| Angelica glauca Edgew. (Umbelliferae) |

| Arnebia euchroma I.M.Johnst. (Boraginaceae ) |

| Betula utilis D.Don (Betulaceae) |

| Fritillaria roylei Hook (Liliaceae) |

| Gentiana kurroo Royle (Gentianaceae) |

| Nardostachys grandiflora DC. (Valerianaceae) |

| Picrorhiza kurrooa Benth. (Scrophulariaceae) |

| Podophyllum hexandrum Royle (Berberidaceae) |

| Saussurea gossypiphora D.Don (Compositae) |

| Vulnerable |

| Aconitum violaceum Jacq. ex Stapf (Ranunculaceae) |

| Allium stracheyi Baker (Alliaceae) |

| Artemisia maritima L. (Asteraceae) |

| Bergenia stracheyi (Hook.f. & Thoms.) Engl. (Saxifragaceae) |

| Ephedra gerardiana Wall. ex Stapf (Ephedraceae) |

| Ferula jaeschkeana Vatke (Apiaceae) |

| Heracleum lanatum Michx. (Apiaceae) |

| Malaxis muscifera (Lindley) Kuntze (Orchidaceae) |

| Meconopsis aculeata Royle (Papaveraceae) |

| Physochlaena praealta (Walp.) Miers (Solanaceae) |

| Polygonatum multiflorum (L.) All. (Liliaceae) |

| Polygonatum verticillatum (L.) All. (Liliaceae) |

| Rheum australe D. Don (Polygonaceae) |

| Rheum moorcroftianum Royle (Polygonaceae) |

| Rheum spiciforme Royle (Polygonaceae) |

| Rheum webbianum Royle (Polygonaceae) |

| Rhododendron anthopogon D.Don (Ericaceae) |

| Rhododendron campanulatum D.Don (Ericaceae) |

| Rhododendron lepidotum Wall. ex D. Don (Ericaceae) |

| Saussurea obvallata (DC.) Edgew. (Asteraceae) |

| Lower Risk-near Threatened |

| Hippophae rhamnoides L. (Elaeagnaceae) |

| Hyoscyamus niger L. (Solanaceae) |

| Lower Risk-least Concern |

| Selinum tenuifolium Wall. ex DC. (Apiaceae) |

| Selinum vaginatum (Edgew.) C.B. Clarke (Apiaceae) |

| Data Deficient |

| Aconitum chasmanthum Stapf ex Holmes (Ranunculaceae) |

| Not Evaluated |

| Ferula narthex Boiss. (Apiaceae) |

| Inula racemosa Hook.f. (Asteraceae) |

| Saussurea costus (Falc.)Lipsch (Asteraceae) |

| * Plants are categorized according to the IUCN Red List Criteria as part of the Biodiversity Conservation Prioritization Project. |

Rishi documenting traditional healing system practices at FRLHT grounds. Photo ©2004 Sarah Khan.

India’s Medical Heritage: A Story of Promise and Erosion

Based on ancient practices, contemporary Indian healing

traditions are accessible to most households because they rely upon locally

available plant material and are deeply rooted in local and traditional

culture. The indigenous Indian medical heritage comprises 2 streams of

knowledge. One stream is based on written traditions (codified) such as

Ayurveda, Siddha, Swa-rigpa (Tibetan), and Unani medical systems (see Table 4

on page 47). The second stream is based on oral traditions (non-codified)

passed down from generation to generation within a family or tribal community.

Both of these streams are found throughout India and together constitute the

Indian health traditions. Although in recent times these rich medical

traditions have eroded and become marginalized because of internal and external

social, economic, and political factors, this does not mean the traditions are

medically inefficient or ineffectual.

| Table 4. Medicinal Plants Utilized in India’s Medical Systems |

| System |

Estimated number of plant species utilized |

Tradition |

Ayurveda

|

1769 |

Codified |

| Folk |

4671 |

Non-codified |

| Homeopathy |

482 |

Codified |

| Siddha |

1121 |

Codified |

| Tibetan |

279 |

Codified |

| Unani (Greco-Arabic) |

751 |

Codified |

| Source: Research, Database, and Survey Department, FRLHT. The Key Role of Forestry Sector in Conserving India’s Medicinal Plants: Conceptual and Operational Features. Bangalore, India: FRLHT; 1999:1. |

FRLHT laboratory plant specimens. Photo ©2004 Sarah Khan.

The Codified Systems

Ayurveda

The foundations of contemporary Ayurveda (the science of

life) are based on the classical Sanskrit texts of Charaka and Susruta Samhitas from around the first centuries CE. These and later

texts contain detailed information on all aspects of health and disease. The

basic theories of Ayurvedic medicine are related to the Hindu Sankhya

philosophical system. The Ayurvedic codified stream of medical knowledge covers

8 broad areas: Kaaya chikitsa

(general medicine), Bala chikitsa

(pediatrics), Gruha chikitsa

(psychiatry), Oordhwanga chikitsa

(ear, nose, throat, and eye), Salya chikitsa (surgery), Damshtra chikitsa (toxicology), Jara chikitsa (rejuvenation), and Vajeekarana chikitsa (virilification).

According to Ayurveda, all matter is a combination of the 5

elements. Like the universe, all matter consists of earth (prithvi), water (jala), fire (agni), air (vayu), and space (akasha) in different proportions. Combinations of the 5

elements condense into the 3 doshas (Tridosha): vata

(air and space), pitta (fire and

water), and kapha (water and

earth). A dosha is any fault or

error, any transgression against the rhythm of life that promotes imbalance. The

3 doshas regulate different

functions in the body. For example, vata represents all motion in the body and mind; pitta represents any type of transformation; and kapha represents stability. Life is inconceivable without

these 3 activities and any imbalance may result in disease.

FRLHT laboratory with dried specimens. Photo ©2004 Sarah Khan.

Siddha

Dravidian culture is the source of Siddha medical arts

(originally, a siddhar was a devotee of

the god Shiva; a siddhi is one

who has achieved extraordinary power). Much of the early medical classics such

as Agathiya Vaidhya Rathina Churukkam and Agashtiya Vaidya Kaviyam have been attributed to sage Agasthiya, the patron saint of the

southern area of Tamil. Agasthiya is said to have communed with the Gods and to

have been gifted with profound knowledge. He is said to have set down the rules

of the Tamil language and of Siddha medicine. According to tradition between

the 10th and 12th centuries CE, 18 additional Siddhas contributed to the growth

of Siddha medicine. Sharma states that the basic concepts of Siddha medicine

and Ayurveda are similar; however, differences arise due to local and

aboriginal traditions that are based on Dravidian culture.11

Tibetan

In the seventh century, King Songtsen Gampo facilitated the

flowering of Tibetan medicine. Eager to develop relations with neighboring

countries, the monarch invited physicians from India, China, and Iran to the

Tibetan court. Translations of these different medical traditions into the new

Tibetan language occurred at this time and continued under the patronage of

later kings. Later, physicians from Kashmir, Nepal, and Turkic regions of

Central Asia also contributed to the evolving Tibetan healing arts.12

Modern day Tibetan medicine is therefore an amalgam of Asian and Near Eastern

medical traditions in addition to Tibetan aboriginal traditions.13

Unani

Unani medicine originated in Greece. The Unani theoretical

framework is based on the teachings of Hippocrates (460-377 BCE). The

Greco-Roman physician Galen (131-210 CE) also greatly developed Greek medical

philosophy and practice. Later noted Arab physicians Rhazes (850-925 CE) and

Avicenna (aka Ibn Sina 980-1037 CE) further developed Unani medicine. Like

Tibetan medicine, Unani was influenced by contemporary systems of traditional

medicine in Egypt, Syria, Iraq, Persia, India, China, and other Near, Middle,

and Far East countries.

In the South Asian subcontinent, Arabs introduced the Unani

system. When Mongols invaded Persia and Central Asia in the early 13th century,14

Unani scholars and physicians found refuge in South Asia because India had good

relations with Persia where economic and political conditions proved more

favorable.15 The Delhi Sultan, the Khiljis, the Tughlaqs, and the

Mughal (aka Moguls, a word derived from Mongol who invaded India after settling in Persia) Emperors provided state

patronage to the scholars and even enrolled some as state employees and court

physicians. From the 13th to 17th centuries Unani medicine flourished.

Practitioners and scholars who have made valuable contributions to Unani are

Abu Bakr Bin Ali Usman Ksahani, Sadruddin Damashqui, Bahwa bin Khwas Khan, Ali

Geelani, Akbal Arzani, and Mohammad Hashim Alvi Khan.

Traditionally, transmission of classical knowledge was

mainly non-institutional from physician to chosen student. Colleges for

traditional medicine were not established until the end of the British colonial

period (circa late 1940s). Today, however, there are over 300 poorly-funded

traditional medical colleges imparting education in various systems of medicine

through a five-and-a-half year program similar in structure to Western

biomedicine programs. At present only a graduate of a recognized medical school

is legally entitled to practice traditional (i.e., Ayurveda, Unani, Siddha)

medicine.

Non-Codified Systems

On the other hand, the transmission of non-codified healing

traditions occurs mainly through family or community traditions. This exchange

is a people-to-people process, from guru (teacher) to shishya (student), guided by local, cultural, and ethical

codes. Today, people in villages, towns, and cities across the country depend

upon local Indian traditional medical systems. It is estimated that there are

more than 600,000 licensed practitioners of contemporary Indian systems of

medicine throughout India.16 In rural communities alone, there are

an estimated one million traditional village-based practitioners of indigenous

medicine. This includes traditional birth attendants, bonesetters, herbal

healers, and wandering monks. In addition to these specialized folk carriers,

there are millions of women and elders who possess traditional knowledge of

herbal home remedies and nutrition. The culture also supports specialized

carriers with no legal status but who possess a definite social legitimacy in

their own localities. Other specialized healers whose resources are greatly

under-researched are those of the indigenous veterinarians who treat a wide

range of animal ailments using local resources.

There are numerous examples of these traditional healers.

Every village in India has a few traditional birth attendants (TBA). The TBA is

able to deliver a stillborn fetus, a breach fetus, a fetus in the lateral

position, and a fetus with the umbilical chord around the neck.16

Another type of practitioner is the bare-foot orthopedic healer or bonesetter.

Every cluster of 20 to 25 villages has a bonesetter. Bonesetters treat sprains,

simple fractures, and in some areas treat compound fractures with open wounds.

In rural India it is estimated that traditional bonesetters treat 50% of broken

bones. For the treatment of snakebites, the traditional visha (poison) healers are able to distinguish a poisonous

snakebite from a non-poisonous one and between the bite of a krait, pit-scaled

viper, Russell’s viper, or cobra. For all of these types of bites, the visha healers are able to provide treatments. In some

regions, visha healers are known to treat the bite of rabid dogs to prevent

rabies. The treatments vary from region to region, however, and no systematic

evaluation about efficacy has been conducted.

Throughout India, surveys of contemporary specialized folk

practitioners indicate a rapid decline in the practice and transmission of oral

healing traditions to the younger generations. Across all categories of

healers, the average age group of the practitioner is above age 45.17

To offset this decline, FRLHT works to organize the many specialized

contemporary local healers in India. According to FRLHT, it is essential to

utilize these healers and their knowledge for several reasons. First, the local

healers are inexpensive or free compared to the cost of modern conventional

treatments. Second, the specialized healers live in the communities they serve

and are part of the local culture. Third, they utilize locally available

resources. And finally, the local healers represent a large resourceful group

already trained to various degrees to serve their individual communities. To

permit their decline will further diminish Indian ethnomedical, cultural, and

biological diversity.

Crisis of Resources—Medicinal Plants under Threat

Around 70% of India’s medicinal plants are found in the

tropical areas, mostly in the various forest types spread across the Western

and Eastern Ghats, Vindhyas, Chotta Nagpur plateau, Aravalis, the Terai region

in the foothills of the Himalayas, and the northeast. Less than 30% of the

medicinal plants are found in the temperate and alpine areas, although many

important medicinal plant species come from alpine regions. A small number of

medicinal plants are also found in aquatic habitats and mangroves.18

Today, there is an urgency

to conserve India’s medicinal plants. An estimated 800 species are currently

used in industry for large-scale production of herbal products. But less than

20 species are under commercial cultivation; that is, more than 95% of

medicinal plants used by the Indian industry are collected from the wild. More

than 70% of the collections involve destructive harvesting from the wild

because of the removal of parts like roots, bark, wood, stem, and the whole

plant.18 The level of impact and destruction from these practices

depends on which methods are used in harvesting, the rate of regeneration of

the different types of plants, and other variables. This poses a definite

threat to the genetic stocks and to the diversity of medicinal plants.

Due to rapid degradation and loss of natural habitats and

the over-harvesting of some species, much of the biological wealth that is

intrinsically important to traditional systems of medicine has been destroyed

or has become threatened. The latest global Red List of plants released by the

IUCN presents an alarming picture: nearly 34,000 species, or 12.5% of the

world’s flora, are facing extinction.19 Based on these figures, one

can estimate that approximately 1,000 of India’s 8,000 medicinal plant species

may also be threatened. A threat assessment survey conducted in northern and

southern India, as per latest IUCN guidelines, has highlighted approximately

200 species of medicinal plants that are under various degrees of threat.20

(See Table 3 on page 45.)

The Convention on

International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) has listed 11 Indian

medicinal plant species in its schedules21 (see Table 5 on

page 47). In 1998 the government of India,

under the Export and Import Policy, recommended restrictions on the export of

approximately 29 plant species, plant products, and their derivatives from the

wild, except when used in formulations. The 29 species include the CITES listed

species and those based on Botanical Survey of India assessments.22

If urgent conservation action is not taken immediately, India stands in danger

of irretrievably losing this priceless medicinal plant heritage.

| Table 5. Endangered Medicinal Plants in India* |

Botanical name & Authority

|

Family |

Sanskrit name |

| Aquilaria malaccesis Lam. |

Thymelaeaceae |

agaru, aguru |

| Cibotium barometz (L.) J. Smith |

Cyatheaceae |

Not available |

| Dendrobium nobile Lindl. |

Orchidaceae |

Not available |

| Dioscorea deltoidea Wallex Kunth. |

Dioscoreaceae |

Not available |

| Nardostachys grandiflora DC. |

Valerianaceae |

jatamansi, jatamamsi |

| Picrorhiza kurrooa Benth. |

Scrophulariaceae |

katuka, katuki |

| Podophyllum hexandrum Royle |

Berberidaceae |

laghapattra, vakra |

| Pterocarpus santalinus L.f. |

Fabaceae |

raktachandana, tilaparni |

| Rauvolfia serpentina (L.)Benth.ex Kurz. |

Apocynaceae |

sarpagandha, nakuli |

| Saussurea costus (Falc.) Lipsch. |

Asteraceae |

kustha, vapya |

| Taxus wallichiana Zucc. |

Taxaceae |

talisapatra, barahmi |

| * Plants are categorized as endangered according to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITIES) |

FRLHT’s Pioneering Program for In Situ Conservation

Since 1993, FRLHT has pioneered the in situ conservation of India’s medicinal plant diversity in

conjunction with the state forest departments (SFDs) in the states of

Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, as well as with

local communities, non-governmental organizations (NGO), and research

institutions. In situ gene banks, also called Medicinal Plant Conservation Areas (MPCAs), have been

established at 55 sites. The need to involve local communities is based on 2

realistic assumptions. First, to ensure effective conservation action, support

and cooperation from local communities is critical. Second, women and folk

healers have traditionally been the custodians of medicinal plant knowledge and

resources. Therefore, local

communities must be involved in and benefit from any effort to promote

conservation and sustainability.

These MPCAs represent the largest effort of its kind in the

country and perhaps in the tropical world. This conservation program is the

most cost-effective and comprehensive strategy for establishing field gene

banks on the inter- and intra-specific diversity of wild medicinal plants.23

Key Features of In

Situ Gene Banks: Medicinal Plant

Conservation Areas

FRLHT promotes the establishment of in situ conservation

strategies versus ex situ ones. An in situ environment, especially one that has

had indigenous peoples living in a biodiversity hot spot for thousands of

years, provides an environment where plant diversity at the genetic, species,

and ecosystem level can be conserved on a long-term basis. Unless plant

populations are conserved in situ (i.e.,

in their natural habitat), they

run the risk of extinction. Medicinal plant populations have large and often

disjunctive areas of distribution, but there are also endemic species confined

to a few pockets. Conservation of these disparate and widely separated

populations is possible only by establishing a network of representative

medicinal plant conservation reserves with a broadly common management

framework. This network ideally includes areas within and outside the existing

protected area network. This network would serve as a chain of field gene banks

for medical plants and as wild germplasm repositories.

In the Medicinal Plant Conservation Area (MPCA) model, a

network of approximately 10 conservation sites is officially designated for

each state of 200 to 300 hectares. (The number of sites per state may vary

depending on the size of the state.) In Southern India, the sites are located

in relatively undisturbed forests of varying vegetation types, lying in different

altitude ranges, soil types, and rainfall patterns. This is an attempt to

capture the wild populations of medicinal plant diversity of the state across

the MPCA network. Forest areas with high biodiversity, sites traditionally

valued for medicinal plant diversity, or sites with known red-listed medicinal

plant species are identified for creating an MPCA. The MPCA boundaries may

correspond to the natural boundary features of the selected site, and ideally

an MPCA should be located in a discrete micro watershed. The MPCAs are

categorized as no-harvest sites. Their protection and management involves the

participation of the local communities. This involvement and support of local

communities are essential to sustain the MPCA on a long-term basis. In order to

meet the community requirements, the forest department is required to establish

medicinal plant nurseries in the MPCA and to supply local households with (1)

plant species of high economic value to grow and sell, and (2) medicinal plant

seedlings for their primary health care needs.

At MPCA sites, detailed

botanical studies are implemented that help forest departments learn what

plants exist in the MPCA gene banks and understand the natural conditions of

the plants’ habitats. Such studies across the MPCA network provide reliable

information on the presence, distribution, and distribution patterns of

medicinal plants across the various forest types in the state. The studies also

correlate the occurrence of medicinal plants with various ecological parameters

such as soil type, soil pH, rainfall pattern, and altitude range. These data on

inter- and intra-specific variations are essential for the management of the

MPCA gene banks. Coupled with studies on threat assessment and trade, these

data also provide informed and focused conservation actions such as species

recovery programs. In addition, the analysis of the botanical, ecological, and

socio-economic studies on utilization and trade conducted across the MPCA

provides guidelines for the Department on Management of Medicinal Plants

regarding the state’s forests. Based on the medicinal plant conservation

program in South India, the Government of India Planning Commission in 2000

recommended the following: (1) the establishment of in situ gene banks (MPCAs)

throughout the Indian subcontinent, and (2) national and state level boards to

manage the MPCAs and development activities.

The MPCAs have 4 major management areas: field research,

community conservation education, nursery outreach program, and local community

participation.

Field Research Activities

Forty-nine red-listed medicinal plants are found in the MPCA

sites selected for research activities (see Table 6 on page 48). This includes

both endemic and non-endemic species. Endemic species are assigned a global

status and non-endemic species have been assessed at the state level. Botanical

studies on the conservation of the red-listed plants are underway with the

cooperation of 3 Indian research institutes: Ashoka Trust for Research in

Ecology and Environment (ATREE), Bangalore (Karnataka); Institute of Forest

Genetics and Tree Breeding (IFGTB), Coimbatore (Tamil Nadu); and Tropical

Botanical Gardens Research Institute (TGBRI), Thiruvananthapuram (Kerala). The

major emphasis is on the species recovery program for the critically endangered

and economically important medicinal plant species.

Table 6. Red–Listed Species within the Medicinal Plant Conservation Areas

Note: The 49 red-listed species below are arranged alphabetically. |

| Latin Binomial, Authority, Family |

Threat Category (State-wise) |

| Karnataka |

Kerala |

Tamil Nadu |

| Adenia hondala (Gaertn.) De Wilde (Passifloraceae) |

VU |

VU |

EN |

| Ampelocissus indica Planch. (Vitaceae) |

EN |

EN |

EN |

| Aphanamixis polystachya (Wall.) R.N.Parker (Meliaceae) |

VU |

VU |

DD |

| Aristolochia tagala Cham. (Aristolochiaceae) |

VU |

LC |

DD |

| Artocarpus hirsutus Lam. (Moraceae) |

VU |

|

|

| Canarium strictum Roxb. (Burseraceae) |

VU |

VU |

VU |

| Celastrus paniculatus Willd. (Celastraceae) |

NT |

VU |

NT |

| Chonemorpha fragrans Alston (Apocynaceae) |

EN |

VU |

DD |

| Cinnamomum macrocarpum Hook.f. (Lauraceae) |

VU |

|

|

| Cinnamomum sulphuratum Kurz (Lauraceae) |

VU |

|

|

| Coscinium fenestratum Colebr. (Menispermaceae) |

CR |

CR |

CR |

| Curcuma pseudomontana J. Graham (Zingiberaceae) |

VU |

|

|

| Diospyros paniculata Dalzell Ebenaceae |

VU |

|

|

| Dipterocarpus indicus Bedd. (Dipterocarpaceae) |

EN |

|

|

| Drosera indica L. (Droseraceae) |

EN |

LC |

LC |

| Drosera peltata Sm. ex Willd. (Droseraceae) |

EN |

VU |

EN |

| Dysoxylum malabaricum Bedd. ex C.DC. (Meliaceae) |

EN |

|

|

| Embelia ribes Burm.f. (Myrsinaceae) |

VU |

NT |

VU |

| Garcinia gummi-gutta (L.) N.Robson (Clusiaceae) |

NT |

|

|

| Garcinia morella Desr. (Clusiaceae) |

VU |

NT |

VU |

| Gloriosa superba L. (Colchicaceae) |

VU |

VU |

LC |

| Glycosmis macrocarpa Wight (Rutaceae) |

VU |

|

|

| Holostemma ada-kodien Schult. (Asclepiadaceae) |

VU |

EN |

NT |

| Hydnocarpus alpina Wight (Flacourtiaceae) |

VU |

|

|

| Hydnocarpus pentandrus (Buch.-Ham.) Oken Allg. Naturgesch. (Flacourtiaceae) |

VU |

|

|

| Kingiodendron pinnatum Harms (Fabaceae) |

VU |

|

|

| Knema attenuata Warb. (Myristicaceae) |

NT |

|

|

| Myristica dactyloides Wall. (Myristicaceae) |

VU |

VU |

LC |

| Myristica malabarica Lam. (Myristicaceae) |

VU |

|

|

| Nervilia aragoana Gaudich. (Orchidaceae) |

NT |

VU |

EN |

| Nothapodytes nimmoniana (J. Graham) (Icacinaceae) |

EN |

VU |

VU |

| Ochreinauclea missionis (Wall.ex G.Don) Ridsdale |

VU |

|

|

| Persea macrantha (Nees) Kosterm. (Lauraceae) |

EN |

VU |

EN |

| Piper barberi Gamble (Piperaceae) |

CR |

|

|

| Piper longum L. (Piperaceae) |

NE |

NT |

EN |

| Piper mullesua Buch.-Ham. (Piperaceae) |

CR |

NT |

VU |

| Piper nigrum L. (Piperaceae) |

NT |

LC |

NT |

| Plectranthus nilgherricus Benth. (Lamiaceae) |

EN |

|

|

| Pseudarthria viscida Wight & Arn. (Fabaceae) |

VU |

VU |

NT |

| Rauvolfia serpentina Benth. ex Kurz (Apocynaceae) |

EN |

EN |

EN |

| Rhaphidophora pertusa (Roxb.) Schott (Araceae) |

VU |

LC |

NT |

| Salacia reticulata Wight (Celastraceae) |

CR |

DD |

NE |

| Santalum album L. (Santalaceae) |

VU |

EN |

EN |

| Semecarpus travancorica Bedd. (Anacardiaceae) |

EN |

|

|

| Smilax zeylanica L. (Smilacaceae) |

NT |

VU |

LC |

| Symplocos cochinchinensis S. Moore (Symplocaceae) |

NT |

LC |

LC |

| Symplocos racemosa Roxb. (Symplocaceae) |

VU |

DD |

NT |

| Trichopus zeylanicus Gaertn. (Dioscoreaceae) |

CR |

|

|

| Vateria indica L. (Dipterocarpaceae) |

VU |

|

|

| Key for Threat: CR = Critically endangered; EN = Endangered; VU = Vulnerable; NT = Near Threatened; LC = Least Concern; DD = Data deficient; NE = Not Evaluated. |

Left: Mr. Muttaiah at Savandhi Herbs store outlet in Savandurga, Karnataka. Right: Savandhi Herbs products. Photos ©2004 Sarah Khan.

Savandhi Herbs staff: Mr. Lokesh-Secretary; Mr. Jayadevaiah-President; and Mr. Narasimhiah-Member, MPCA guard. Photos ©2004 Sarah Khan.

Community Conservation Education Activities

In the Topslip MPCA in the state of Tamil Nadu, a

conservation educational facility has been established with a demonstration

garden and self-guided nature trail, attracting upwards of 1,000 tourists per

day. In the area of Karpakpalli (Karnataka), medicinal plant exhibitions have

been organized. In another 20 sites, nature camps provide valuable conservation

education to school children.

Nursery Outreach Program Activities

Presently 20 MPCA nursery sites exist. The state forest

departments (SFDs), in collaboration with the local communities, have promoted

the development of these nurseries. For example, in Agastiarmalai (Kerala)

medicinal plants are grown to provide seedlings for women’s self-help groups,

local folk healers, local homes, schools, and community herbal gardens.

Community Participation Activities

Local populations and communities benefit from

income-generating activities. For example, small-scale processing units, such

as Savandhi Herbs at Savandurga (Karnataka) and Dhare Shri at Sandur

(Karnataka), have been established to generate income around the MPCA.

Currently, women’s self-help groups produce 23 products for use in primary

health care. These include the classic Ayurvedic formulation Triphala churna,

which is a mixture of the following: (1) the powder from the fruits of Emblica

officinalis Gaertn., Euphorbiaceae;

Terminalia bellerica (Gaertn.) Roxb.,

Combretaceae; and T. chebula

Retz.; (2) the highly revered tonic root ashwagandha (Withania

somnifera [L.] Dunal, Solanaceae) powder;

and (3) erand thaila or castor

seed oil (Ricinus communis L.,

Euphorbiaceae). Managed by the local community members, sales-outlets have been

established to sell seedlings and processed products.

Conclusions

In the spirit of the Chiang Mai and Bangalore Declarations,

FRLHT has pioneered in situ conservation in southern India to avoid the erosion

of both biological and cultural diversity. FRLHT’s efforts are essential to

preserving and developing the rich ancient ethnomedical heritage of the Indian

subcontinent. Furthermore, field research, community conservation, nursery

development programs, and local community participation are tangible results of

in situ conservation sites. In fact, these 55 MPCA sites represent models for

other communities worldwide to implement for maintaining their own indigenous

health traditions along with biological and cultural diversity.

Sarah K. Khan is a PhD candidate in Ethnobotany at

Graduate Center of City University/New York Botanical Garden. With a Fulbright

Scholarship, Phipp’s Botany in Action grant, and Committee of the American

Overseas Research Centers Smithsonian grant, she is researching Ayurvedic and

Chinese medicinal plants in India and China. She has an MS in Clinical

Nutrition and a Master’s of Public Health degree, both from Columbia

University. E-mail: skkhan@charter.net.

N. Mohan Karnat is a forest officer working with FRLHT

for the Medicinal Plants Conservation project in the South Indian states.

E-mail: mkarnat@yahoo.com or cftmb@sancharnet.in.

Darshan Shankar is the founder and director of FRLHT,

Bangalore, and the recipient of the Richard and Hinda Rosenthal Center for

Complementary and Alternative Medicine Award at Columbia University for

International Culture Stewardship. E-mail: darshan.shankar@frlht.org.in.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the entire staff of FRLHT

for their invaluable contributions to the contents of this article and Mr.

Steven Foster for his editorial assistance.

References

1. International

Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN) Medicinal

Plants Specialist Group. Available at:

http://www.iucn.org/themes/ssc/sgs/mpsg/main/Why.html. Accessed June 17, 2005.

2. Meffe

GK, Carroll CR, eds. Principles of Conservation Biology, 2nd ed. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates, Inc.,

Publishers; 1997:87.

3. Nabhan

GP. Cultures of Habitat: On Nature, Culture, and Story. Washington, DC: Publishers Group West,

Counterpoint; 1997.

4. Posey

DA, Dutfield G. Beyond Intellectual Property: Toward Traditional Resource

Rights for Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities. Ottawa, ON, Canada: International Development Research Center; 1996.

5. Raven

PH. Medicinal Plants and the Global Sustainability: The Canary in the Coal

Mine. In: Medicinal Plants: A Global Heritage. Proceedings of the

International Conference on Medicinal Plants for Survival. February 16-19, 1998. Bangalore, India:

FRLHT/International Development Research Centre; In Press:14-18.

6. The Chiang

Mai Declaration: Saving lives by saving plants [WWF Web site]. In: Guidelines

on the Conservation of Medicinal Plants,

Annex 1:34. Available at:

http://www.wwf-uk.org/filelibrary/pdf/guidesonmedplants.pdf. Accessed June 15,

2005.

7. Bangalore

Declaration. In: Medicinal Plants: A Global Heritage. Proceedings of the

International Conference on Medicinal Plants for Survival. February 16-19, 1998. Bangalore, India:

FRLHT/International Development Research Centre; In Press.

8. Farnsworth

NR. Ethnopharmacology and drug development. In: Prance GT,

Chadwick DJ, Marsh J, eds. Ethnobotany and the Search for New Drugs.

Ciba Foundation Symposium 185. England:

John Wiley and Sons; 1994.

9. Leaman

D. Conservation Priorities for Medicinal Plants. In: Medicinal Plants: A

Global Heritage. Proceedings of the International Conference on Medicinal

Plants for Survival. February 16-19, 1998.

Bangalore, India: FRLHT/International Development Research Centre; In

Press:2-13.

10. IUCN

2004. 2004 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Available at: www.redlist.org. Accessed June 17, 2005.

11. Sharma

PV. Siddha Medicine. In: Sharma

PV, ed. History of Medicine in India: From Antiquity to 1000 A.D. New Delhi: Indian National Science Academy; 1992.

12. Shrestha

R, Baker IA. The Tibetan Art of Healing.

San Francisco, CA: Chronicle Books; 1997.

13. Grossinger

R. Planet Medicine: Origins. Berkeley,

CA: North Atlantic Books; 1995.

14. Wink

A. Al-Hind The Making of the Indo-Islamic World, Vol II: The Slave Kings and

the Islamic Conquest 11th-13th Centuries.

New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 1997:13.

15. Jaggi

O. Unani Medicine in India. In:

Chattopadhyaya DP, ed. History of Science, Philosophy and Culture in

Indian Civilization. Vol IX, Part 1: Medicine in India: Modern Period. New Delhi: Oxford University Press; 2000:320.

16. Shankar

D. Agenda for Revitilisation of Indian Medical Heritage. In: Report of The

Independent Commission on Health in India.

New Delhi: Voluntary Health Association of India; 2001.

17. FRLHT.

FRLHT Annual Report 1999-2000.

Bangalore: Anugrha Prints; 2000.

18. FRLHT.

The Key Role of Forestry Sector in Conserving India’s Medicinal Plants:

Conceptual and Operational Features.

Sponsored by Conservation Science Division, Ministry of Environment and

Forests. New Delhi: Government of India; November 1999:2-4.

19. Walter

KS, Gillet HJ, eds. 1997 IUCN Red List of Threatened Plants. Compiled by the World Conservation Monitoring

Centre. IUCN-The World Conservation Union, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge,

UK; 1998.

20. Ravikumar

K, Ved DK. Illustrated Field Guide: 100 Red Listed Medicinal Plants of

Conservation Concern in Southern India.

Bangalore: FRLHT; 2000.

21. Conservation

on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES) of Wild Fauna and Flora.

CITES Guide to Plants in Trade. United

Kingdom: Department of the Environment; 1994.

22. Government

of India. Notification No. 24 (RE-98)/1997-2002, Dated 14-10-98. New Delhi:

Ministry of Commerce; 1998.

23. FRLHT.

The Key Role of Forestry

Sector in Conserving India’s Medicinal Plants: Conceptual and Operational

Features. Sponsored by Conservation Science

Division, Ministry of Environment and Forests. New Delhi: Government of India;

November; 1999:9.

Sidebar: FRLHT’s Efforts Go Beyond Conservation

In addition to its primary work in the area of ethnobotanical and medicinal plant conservation, FRLHT has established numerous projects and programs:

• Built a database of the Materia Medica of Ayurveda and Siddha traditions based on primary medical texts covering the period from 1500 BCE to 1900 CE.

• Initiated a pioneering project on rapid assessment of local health practices in 13 communities spread across rural South India.

• Developed educational materials to disseminate reliable knowledge on Indian medicinal plants and traditional knowledge of local health traditions. This includes books, videos, and a popular traditional healthcare magazine entitled Amruth, which is dedicated to the dissemination of information on medicinal plants.

• Publishes scientific articles on issues of medicinal plant conservation, trade, biodiversity, medicinal plant chemistry, intellectual property rights, and traditional health systems.

• Established a pharmacognosy laboratory for certification of medicinal plants and for product development.

• Conducts short-term conservation courses for foresters and community leaders. The training modules focus on in situ conservation of medicinal plants and documentation and rapid assessment of local health traditions.

• Maintains and continuously updates rich databases and references collections including: (1) The BOTMAST database of approximately 7300 medicinal plant species, (2) The Ayurveda Nomenclature database with 1.2 million records, (3) An applications database with about 24,000 records, (4) Separate databases on nursery techniques for 300 species and seed storage techniques for 92 species, (5) Trade data on about 800 plants collected from important markets, (6) Eco-distribution maps of red-listed species for over 150 species, (7) An herbarium with over 24,000 voucher specimens of 2500 species.

More information on FRLHT is available at http://envis.frlht.org.in.

|