Issue: 74 Page: 54-61

Illegal Stripping and Conservation of Slippery Elm Trees

by Courtney Cavaliere

HerbalGram.

2007; 74:54-61 American Botanical Council

For the past few years, officials at the Daniel Boone National Forest in Kentucky have received complaints and discovered the girdled remains of slippery elm trees (Ulmus rubra, Ulmaceae syn. U. fulva) illegally stripped of their bark by poachers selling to the herbal market (B. Bishop, oral communication, January 23, 2007). Such thieves are elusive, but US Forest Service officers were able to apprehend several offenders in the summer of 2006.1 Forest officials are working diligently to prevent further stripping of slippery elms, which appear to be joining the ranks of American ginseng (Panax quinquefolius, Araliaceae) root, goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis, Ranunculaceae) root, and other medicinal plants as common victims of illegal harvesting.

The slippery elm is native to North America, with populations extending across much of central and eastern United States and into eastern Canada.2 Its inner bark is coated with a mucilaginous lining, for which the tree earned both its name and its long-standing reputation as a medicinal agent. The bark has demulcent, expectorant, emollient, diuretic, and nutritive properties,2 and it is one of the few herbal materials still classified by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) as an approved, nonprescription, over-the-counter (OTC) drug (See Table 1). Much of the slippery elm bark that reaches the herbal market is acquired through wild-harvesting, which is difficult to validate as legally or sustainably obtained.

Barry Bishop, a law enforcement officer with the US Forest Service, said he began to notice illegally stripped slippery elms in the 706,000-acre Daniel Boone National Forest in 2003 (B. Bishop, oral communication, January 23, 2007). Officials at the forest are aware of around 60 slippery elm trees that have been stripped of their bark over the past few years. Law enforcement officers, however, were unable to catch anyone in the act of perpetrating the crime until 2006. “We were finally at the right place at the right time,” Bishop said. Bishop apprehended 3 individuals who were illegally stripping slippery elm bark in June of 2006. Two of these illegal harvesters had been apprehended shortly beforehand by US Forest Service Special Agent Courtney McCrae for the same crime, and they told Bishop that they were stripping slippery elm bark in order to raise money to pay the ticket for their first offense. Special Agent McCrae apprehended 7 individuals for stealing slippery elm bark in June and August of 2006 (C. McCrae, oral communication, January 30, 2007). The removal of timber or other forest products from public land, without special authorization, is prohibited under Title 36 of the Code of Federal Regulations.3 According to Bishop, federal statute dictates that anyone caught collecting or harvesting forest materials without a permit may be issued a fine ranging from $250 to $5,000 or arrested on charges for “theft or unlawful taking” or “criminal mischief in the first degree.” Six of the individuals caught by McCrae were issued citations ranging from $75 to $275. The three individuals apprehended by Bishop pled guilty to criminal mischief in the second degree and were sentenced to serve 6 months of jail time in Leslie County, KY. “These people were jobless and had no base source of income, so the [state court] didn’t seek [financial] restitution. There wouldn’t have been a point,” Bishop said. “This activity is illegal and we’re going to do what we can to stop it,” said David Taylor, a US Forest Service botanist for the Daniel Boone National Forest (oral communication, January 23, 2007). “Law enforcement officials are keeping their ears to the ground. They’re taking the reports seriously and checking them out.” Although it is possible to harvest the bark of slippery elm trees in a fashion that does not kill the tree—by removing only segments of bark at any given time—some harvesters girdle, and thereby kill, the tree. The inner layers of the bark provide for the flow of water and nutrients throughout the tree, and this process is cut off when the bark is completely or mostly removed.1 The tree literally starves to death. Taylor noted that legal harvest of some materials within the forest is sanctioned when the harvester obtains the appropriate permits. “We do provide permits for many botanicals, such as ginseng or black cohosh,” he said. These permits enable visitors to collect or harvest a set amount of certain herbs or materials from the forest for personal use. “We don’t issue permits for slippery elm bark because it leaves dead or half-dead trees standing, which can be dangerous.” Taylor explained that the stripped trees are often more susceptible to diseases or fungi, which could spread to adjacent trees. Taylor said he did not know if illegal stripping of slippery elms is as prevalent within other state or national forests. “I do know that poaching in general of herbaceous species is pretty high.” Bishop, meanwhile, said he was aware of numerous complaints from private land owners regarding stripped slippery elms.

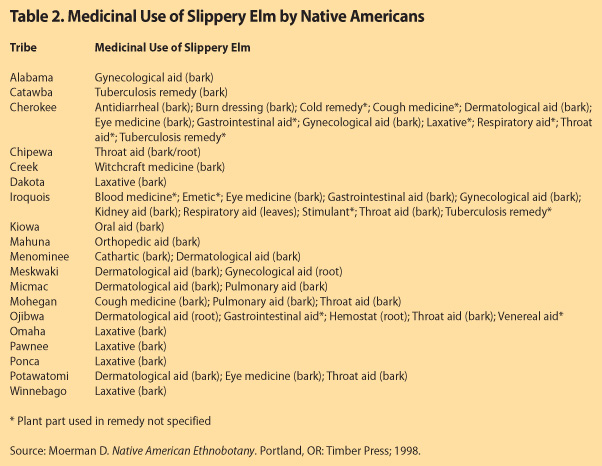

Slippery elm bark has been valued for its medicinal properties for centuries. Various Native American tribes, for instance, employed slippery elm bark as a medicine or food.4 It was utilized as a sore throat remedy by the Iroquois and Mohegan tribes; a laxative by the Omaha, Pawnee, and Dakota tribes; a dermatological aid by the Menominee, Meskwaki, and Potawatomi tribes; and a tuberculosis remedy by the Cherokee, Catawba, and Iroquois tribes—to name just a few (See Table 2). The tree soon became a source of medicine and nutrition for Euro-American settlers as well. It has been reported that soldiers of the Revolutionary War in 1776 subsisted on a jelly created from slippery elm bark after losing their way and being deprived of resources for over a week, and German botanist Prince Maximilian wrote of the medicinal properties of slippery elm in 1832.2 The company Thayers Natural Remedies began producing and marketing slippery elm lozenges in 1847. According to John Gehr, Thayers’ vice-president of sales and marketing, Thayers remains the only company that sells a lozenge containing enough slippery elm material (150 mg) for the botanical to serve as an active ingredient, based on the FDA’s OTC standards (J. Gehr, oral communication, October 24, 2006).5 Gehr claims that Thayers currently uses approximately 10,000 pounds of dried slippery elm bark each year. According to the Tonnage Survey of Select North American Wild-Harvested Plants, 2004-2005, prepared by the American Herbal Products Association (AHPA), the 2005 aggregate harvest of slippery elm bark consisted of 203,984 pounds of dried wild-harvested bark, 1,731 pounds of dried cultivated bark, and 74 pounds of fresh wild-harvested bark.6 The 2004 harvest was much lower, with only 78,380 pounds of dried wild-harvested bark and 803 pounds of dried cultivated bark reported, but data from 2001-2003 show figures on the same level as 2005. Gehr said that, to his understanding, the vast majority of processed slippery elm bark is used as bulk material for supplements and products, primarily as a digestive aid. Thayers purchases its slippery elm bark from third-party suppliers, who obtain the bark through wild-harvesting. “Unfortunately, there’s no way for us to know with certainty what the source of the slippery elm is, because it’s only wild-crafted,” Gehr explained.* Chuck Wanzer of Botanics Trading LLC, a company based in Blowing Rock, NC, which provides ethically wildcrafted and cultivated botanicals, noted that this is a common problem for buyers of wild-harvested plants and materials (C. Wanzer, oral communication, January 9, 2007). Even wildcrafters who obtain their plant materials legitimately often do not like to disclose the locations they used for harvesting, in some cases because they do not want other harvesters to find and infiltrate their sites. “It’s a tradition, especially up in the mountains, to do wildcrafting as a way of life and for the secondary income,” Wanzer stated. According to Wanzer, there are a few ethical herb companies growing slippery elm trees for sustainable use, but the practice is not particularly cost-effective. Slippery elm bark that is certified as organic and sustainably grown usually sells for $9 a pound while non-certified bark typically sells for $4 a pound, making slippery elm one of the more under-priced herbal materials on the market. This low market value may be saving many slippery elms from illegal harvesting. “The illegal stripping of the inner bark of slippery elm trees is unconscionable, but it is not occurring widely in the southern Appalachia area yet, mostly because the price of slippery elm is too low,” said Lynda LeMole, executive director of United Plant Savers (UpS), a nonprofit dedicated to preserving native medicinal plants (e-mail, October 17, 2006). “This is an area where high-priced medicinal plants like American ginseng and goldenseal are abundant, and people are very aware of plant theft.” Wanzer argued that wildcrafting does not pose the greatest threat to slippery elms. “Development and logging are taking out much more of these trees than wildcrafters,” he said. “There is a problem with habitat depletion killing everything—slippery elms included.” Furthermore, once forest areas are cleared, any replanting is usually done in pines and firs, as opposed to elms. Dutch elm disease has taken its toll on some populations of slippery elms as well.2 The many threats facing slippery elms have placed the tree in a rather ambiguous situation. According to Wanzer, slippery elm populations may be threatened in certain areas, but the tree itself is not in any immediate jeopardy as a species. He noted that slippery elms grow across a wide stretch of the United States and that there are plenty of thriving elms throughout the country. Taylor echoed such sentiments: “It’s not a terribly common tree, but it’s not rare either,” he said. Gehr noted that Thayers has not witnessed any significant changes in the availability or cost of slippery elm material in recent years, which could further indicate that the tree’s populations are not seriously threatened. Some organizations, however, are taking precautionary measures to preserve and strengthen slippery elm populations. The National Center for the Preservation of Medicinal Herbs, a nonprofit that researches ways to raise and replenish medicinal botanicals, has placed the slippery elm on its protection list,7 and UpS has similarly added the tree to the organization’s “At Risk” list.8 UpS planted 500 young slippery elms in its botanical sanctuary in Meigs County, OH, in 1998 to both replenish slippery elms and to serve as a possible research site for experimenting with cures for Dutch elm disease and other diseases affecting elms, such as elm phloem necrosis (L. LeMole, e-mail, October 17, 2006). According to LeMole, approximately 90% of the planted elms are still thriving in the sanctuary. “One helpful aspect for slippery elm trees is that each tree casts out a tremendous amount of seed,” said LeMole. “The trees begin producing seed at about 12-18 years of age. Since the wood of the slippery elm (also known as the red elm) is so hard, the trees contract the Dutch elm disease at about 12-18 years old. So it is a race—Can they produce seed before perishing from disease? Therefore, it is important to keep planting the trees and keep them going in the hope that a disease resistant strain will develop or that they can cross to produce a valuable variety that is disease resistant.” Forest officials at the Daniel Boone National Forest are similarly striving to maintain their slippery elm populations. Bishop said the US Forest Service is spreading information about forest regulations to ensure that people understand that stripping slippery elm bark on public land is illegal. The Forest Service has also asked that the public assist in reporting such illegal activities.1,7 “Every species out there plays some role in the environment—including slippery elms,” said Taylor. According to Taylor, the illegal harvesting of any plant from the forest disrupts the natural environment and makes it difficult for forest officials to adequately assess plant populations and determine how various activities are influencing forest species. “The [US Forest Service] is a conservation organization. We want to be able to provide these resources down the road,” he added.

References

- Theft of natural resources occurring on national forest lands [press release]. Winchester, KY: Daniel Boone National Forest; June 27, 2006.

- Strauss P. Slippery Elm. In: Gladstar R, Hirsch P, eds. Planting the Future. Rochester, VT: Healing Arts Press; 2000.

- Title 36. Code of Federal Regulations, Part 261.6(h).

- Moerman D. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland, OR: Timber Press; 1998.

- Food and Drug Administration. Oral health care drug products for over-the-counter human use. 1991. Federal Register. 56:48342-48346.

- American Herbal Products Association. Tonnage Survey of Select North American Wild-Harvested Plants, 2004-2005. Silver Spring, MD: American Herbal Products Association; 2007.

- Jafari S. Trees stripped for medicinal bark for herbal market. Associated Press. July 15, 2006.

- UpS “At-Risk” & “To Watch” List. United Plant Savers Web site. Available at: http://www.unitedplantsavers.org/UpS_At_Risk_List.html. Accessed October 5, 2006.

* HerbalGram received the following comment from a reviewer of this article: “My company [Traditional Medicinals, Inc., Sebastopol, CA] uses nearly as much dried elm bark annually as Thayers, but for many years we have been obtaining it under organic certification rules for wild crops, which have some traceability and transparency requirements. We know where our organic wild elm bark is harvested. I have discussed the sustainable wild harvest management plan with the harvester, and he has invited us to the collection site in order to observe and document the harvest. So it is possible to know more about where your elm is coming from if you can justify paying the premium for organic certification” (J Brinckmann, e-mail, March 28, 2007).

|