Issue: 85 Page: 28-39

“Cinderella” Schisandra: A Project Linking Conservation and Local Livelihoods in the Upper Yangtze Ecoregion of China

by Anthony Cunningham, Josef Brinckmann

HerbalGram. 2010;85:28-39 American Botanical Council

“Cinderella” Schisandra: A Project Linking Conservation and Local Livelihoods in the Upper Yangtze Ecoregion of China

By Anthony B. Cunningham and Josef A. Brinckmann

Ripe fruits of Schisandra sphenanthera. Photo ©2010 Anthony B. Cunningham

Introduction

In the mid-1990s, the term “Cinderella trees” was coined to denote useful tree species that had been overlooked and their economic potential left largely untapped.1 Nanwuweizi (southern schisandra, Schisandra sphenanthera, Schisandraceae) is the “Cinderella” cousin to the better-known and more economically developed beiwuweizi (northern schisandra, S. chinensis). Both are scandent vines (climbers), the fruits of which are recognized in the Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China. Most traditional medicinal use and trade in the past has involved the larger fruits of northern schisandra, as this species is more popular in China. However, southern schisandra has also been used and studied for its medicinal properties, and it could be used increasingly in food and beverage products.

Southern schisandra is the first plant that has been selected as a basis for micro-enterprises by a collaborative project interested in promoting the sustainable management of traditional medicinal plants in China’s Upper Yangtze ecoregion. This article explores the goals of this collaborative project, as well as the important role that southern schisandra could play in improving income for local people through its sustainable harvest outside of nature reserves in the Upper Yangtze ecoregion.

The landscape around Daping, including XiaoHeGou Nature Reserve. Photo ©2010 Anthony B. Cunningham

Landscapes, Conservation, and Livelihoods

The mountain landscapes of the Upper Yangtze River basin are internationally recognized for their rich biodiversity. The Worldwide Fund for Nature (WWF) has designated the river basin as a Global 200 Ecoregion. The term “Global 200” refers to WWF’s strategic approach to conserving the world’s most distinctive ecosystems, prioritized on the basis of their species richness, species endemism, unique species (such as the giant panda), globally rare habitats, or unusual ecological or evolutionary features. At a national level, the Upper Yangtze ecoregion has been identified as the highest priority area for biodiversity conservation in China. These landscapes also contain major watersheds, have one of the world’s most species–rich temperate forests, and are home to many threatened plant and animal species. An estimated 75% of commercially harvested Chinese medicinal plant species are found in the mountains of the Upper Yangtze ecoregion, many endangered due to over-harvesting. For these reasons, a collaborative project between WWF-China, TRAFFIC Beijing office, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), China’s Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM) Bureau, and several provincial forestry bureaus has been developing and implementing a strategic model for biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. Important goals of this project, which is being funded through the EU-China Biodiversity Programme (ECBP), are to address the degradation of the habitats in which medicinal plants occur, the over-exploitation of high-value medicinal plant species that are components of these habitats, and improved livelihoods in these landscapes.

The importance of TCM plant collection to local livelihoods was highlighted recently when, on May 12, 2008, a massive earthquake hit Sichuan province. This was the 19th deadliest earthquake of all recorded history, with at least 69,000 people killed and about 4.8 million people left homeless immediately after the earthquake. Many poorer, rural villages were hardest hit. Even though Sichuan’s 5 largest cities were less affected, it has been estimated that economic losses due to the earthquake could be over USD $75 billion dollars.2 This would make the earthquake one of the costliest natural disasters in Chinese history. What is less widely known is the extent to which wild harvest of medicinal plants increased in the aftermath of the earthquake. Before the earthquake, wild harvest and cultivation of TCM plants already played an important role for poorer people in many of these villages, providing about 30-40% of cash income. After the earthquake, there was a noticeable increase in the number of people harvesting medicinal plants, primarily to get additional cash income for reconstruction costs, before the summer harvest season ended and the plants were difficult to find.3

Historical Context, Demand, and Supply

In planning practical steps for medicinal plant conservation in the Upper Yangtze ecoregion, it was crucial to take 3 aspects of the medicinal plants trade into account: the history of TCM, factors influencing demand for medicinal plants, and factors influencing supply.

Today’s TCM differs from Classical Chinese Medicine (CCM). TCM was standardized by 10 physicians commissioned by Chinese political leader Mao Zedong, who from the 1950s also promoted integration of Chinese and Western medical systems under the slogan “zhongxiyi jiehe” (integration of Traditional and Western Medicine). From the late-1970s to present day, a “three-paths” (plural) healthcare policy (san taio daolu) has been followed, giving equal status to Chinese, Western, and integrated medical systems.4 State support for TCM has directly influenced demand for favored plant species. A good example is the “Barefoot Doctor” program (1965-1981), through which huge quantities of medicinal plants were harvested, generally without any attention to sustainable harvest. Today, TCM is in a new development phase. It is planned that, by the year 2010, a modern TCM innovation system will be established along with a series of standards for modern TCM products to create a competitive, modern TCM industry through new technology and standardization.

Demand for medicinal plants from the Upper Yangtze ecoregion has also been driven by other factors. These include the growing popularity of TCM internationally.4 In Britain, for example, more than 3,000 clinics offer TCM.5 At a global scale, China is by far the largest exporter of medicinal and aromatic plants. In 2007, China exported 241,561,404 kg of medicinal plants classified under the Harmonized System (HS) Code 1211* (which includes botanicals like astragalus root [Astragalus membranaceus, Fabaceae], cordyceps fungus [Cordyceps sinensis, Clavicipitaceae], Asian ginseng root [Panax ginseng, Araliaceae], licorice root [Glycyrrhiza uralensis, Fabaceae], lycium fruit [Lycium barbarum, Solanaceae], rhubarb root [Rheum officinale and R. palmatum, Polygonaceae], and hundreds of others) with a reported value of USD $418,238,990. These plants were mainly exported to Hong Kong (for re-export), Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, and other Asian countries. China additionally exported 709,781,595 kg of aromatic herb and spice plants classified within HS Codes 0902 through 0910. (These chapters include botanicals like capsicum fruit [Capsicum spp., Solanaceae], cassia bark [Cinnamomum aromaticum, Lauraceae], ginger rhizome [Zingiber officinale, Zingiberaceae], green tea leaf [Camellia sinensis, Theaceae], and star anise fruit [Illicium verum, Illiciaceae], among many others, with a reported trade value of USD $1,038,624,084, mainly to Japan, Morocco, the United States, Hong Kong, and Malaysia).6 According to a report published by the Hong Kong Trade Development Council, the global sales for Chinese medicines have grown at a rate of 8% each year since 1994. In 2002, the total global sales were USD $23.2 billion.7 These sales may grow even faster with the growing link to formal, industrialized production and export of TCM preparations.

The world’s highest diversity of TCM species continues to be used within China, where herbal preparations account for 30-50% of total medicinal consumption. The fact that China has an ageing population is also significant. By 2025, one quarter of the world’s population over 60 years old will be in China. This has profound implications for healthcare policy in general and TCM use in particular, as this sector of the population places a particularly high value on TCM. A final factor influencing demand is the rapid increase in buying power in China due to an economy that has averaged a near 10% annual growth of real gross domestic product (GDP) and greater than 8% real GDP per capita since 1978. This increased buying power not only influences consumers to purchase more goods and services, but it also enables people to buy higher quality and costly (often rare) components of TCM in huge quantity. Trade in a favored geographic variety of wendangshen (codonopsis root, Codonopsis pilosula, Campanulaceae) or Sichuan fritillary bulb (Fritillaria cirrhosa, Liliaceae; chuanbeimu in Chinese) are just 2 examples. Fritillaria cirrhosa bulbs are tiny, yet 100 tons of the tiny bulbs are reportedly used each year, with an estimated current (unfulfilled) market demand of 2,000 tons per year from more than 400 industries that produce over 200 kinds of Fritillaria preparations. Annual sales of one of the most popular Fritillaria-based cough syrups (Nin Jiom Pei Pa Kao/Fritillaria Loquat Syrup [Nin Jiom Medicine Manufactory HK Ltd, Tsuen Wan, New Territories, Hong Kong]) is alone worth US $70 million per year.8

Taking Stock: Training and Baseline Surveys

Just as a person may periodically assess how much (or how little) money he or she has in his or her bank account and how quickly that money is accruing interest, there is similarly a need to take stock of wild populations of medicinal plants and the rate at which those stocks are replenishing, or in some cases, possibly dwindling. If this is not done, then there is a risk that stocks of valuable, slow-growing species will be depleted, just as overspending can bankrupt a business.

In the ECBP project, participants were trained to undertake medicinal plant resource assessments and how to use this information to set priorities for conservation, resource management, or cultivation. The participants in this training course were from mixed backgrounds, ranging from skilled foresters and botany professors from local universities to experienced field staff from nature reserves and representatives from local minority groups.

Costs and complexity for sustainable harvest, and of baseline surveys and monitoring, vary with different categories of medicinal plants. Most practical and least complex is the lower impact harvests of fruits, flowers, or leaves from faster-growing, more resilient species. Where these are locally common, sustainable wild harvest is possible from existing populations. Due to its “Cinderella” status in the past, and relatively low levels of harvest, southern schisandra fruits fall within this category. This contrasts with slower-growing, more habitat-specific, and often higher priced medicinal species encountered in the baseline surveys. These often have a long history of harvest of roots, bark, or the whole plants, sometimes since the 1950s, with consequent decline in wild stocks. In such cases, populations need to recover before sustainable harvest is possible, with the baseline surveys followed by monitoring. Examples of this category would be F. cirrhosa (chuanbeimu) and paris root (Paris polyphylla, Liliaceae) (chong lou).

Commercial harvest of remaining populations of slow-growing and often habitat-specific medicinal plants within nature reserves is not just a plant conservation issue. With limited staff, strict controls are difficult in these remote, rugged mountains. As a result, commercial collectors camp within nature reserves during the TCM harvest season, in some cases for 2 months or more, harvesting TCM species and hunting wildlife as a source of food. When hunting of protected animal wildlife such as “gnu-goat” (Budorcas taxicolor, Bovidae) occurs, then conflicts between conservation authorities and TCM collectors increase, often with negative outcomes for both the people and the nature reserves.

What is needed are participatory management plans in place, with harvest rules that are agreed upon and accepted by all stakeholders. Until this happens, and populations of depleted species have been able to recover through enrichment planting or natural regeneration, then species such as P. polyphylla need to have a rest from harvest, through a shift to more resilient, faster-growing species or the harvest of flowers, seeds, or fruits. Better pricing to local harvesters can help compensate for this shift—which is why the next step in the ECBP project will be management plans linked to niche markets for southern schisandra fruits.

Southern Schisandra in Traditional Chinese Medicine

The currently official edition of the Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China (PPRC English Edition 2005)9 assigns the same “actions” and “indications for use” for both northern and southern schisandra, and at the same dosage level. Each has a separate monograph due to their different botanical identification descriptions, tests, and quantitative assays, but the therapeutics sections of the monographs are identical, suggesting that these 2 species could be interchangeable for TCM formulations in clinical practice. Indeed they have a history of substitution, and whenever supplies of northern schisandra are low (as they have been in recent years, in part due to significantly increasing imports from Europe, Japan and Korea), demand for southern schisandra increases, and it is used in TCM formulations and products in place of northern schisandra. Presently, the Chinese Pharmacopoeia Commission has assigned the following therapeutic information for both northern and southern schisandra fruit:

Action: To astringe, replenish qi† promote production of body fluids, tonify the kidney,‡ and induce sedation.

Indications: Chronic cough and dyspnea, nocturnal emission, spermatorrhea; enuresis, frequent urination; protracted diarrhea; spontaneous sweating, night sweating; impairment of body fluids with thirst, shortness of breath and feeble pulse; diabetes and wasting-thirst caused by internal heat;§ palpitation and insomnia.

Dosage: 1.5-6.0 g (dried fruit for preparation as aqueous decoction).

There are also applications in TCM where southern schisandra would be processed with vinegar. Twenty kg of vinegar is added for each 100 kg of cleaned, dried southern schisandra in a suitable vessel, mixed thoroughly, then steamed until the herbal drug becomes black in color. The drug is removed and dried, after which its appearance is externally brownish-black and shrunken; the pulp usually adheres closely to the seeds and is not viscous. Vinegar-processed southern schisandra is broken into pieces before use.

Despite the apparent allowance in the current Chinese medical system to interchange the 2 species, there is some controversy within the Chinese practitioner community as to whether the same functions and properties can be assigned, even in the context of traditional medicine. Since at least the time of the Qing Dynasty (1644 CE to 1912 CE), northern schisandra fruit and southern schisandra fruit have been considered as having different actions and functions by practitioners of TCM. There is strong belief today among some practitioners that northern schisandra fruit is superior and that its indications should be differentiated from southern schisandra.

Additionally, there is controversy as to whether southern and northern schisandra may be classified similarly as adaptogens. Adaptogenic substances are supposed to have the capacity to normalize body functions and strengthen systems compromised by stress. Along with Asian ginseng root, eleuthero root (Eleutherococcus senticosus, Araliaceae), and rhodiola root (Rhodiola rosea, Crassulaceae), northern schisandra fruit preparations have been the subject of many animal and human clinical studies investigating their adaptogenic potential.10 Because southern schisandra fruit has not yet been studied for adaptogenic potential, there are no data suggesting that it can be used interchangeably with northern schisandra for this nontraditional new use. Pharmacological and clinical research on preparations of southern schisandra fruit have been increasing only recently. Researchers at Flavex® Naturextrakte, a German manufacturer of a CO2 extract of southern schisandra fruit, have carried out a study on the biological activity of different extracts from S. sphenanthera, concluding that these might be useful in the prevention and treatment of hyperproliferative and inflammatory skin diseases.11 In 2009, studies on the effects of southern schisandra fruit extract on the pharmacokinetics of the conventional drugs tacrolimus (an immunosuppressive drug) and midazolam (an ultra short-acting benzodiazepine derivative) in healthy volunteers were published.12,13

Southern Schisandra in Food and Beverage

In China, southern schisandra is also used in local non-medicinal food and beverage products (e.g., in fruit juices, soups, alcoholic- and nonalcoholic beverages) and has the potential for global application as a component of healthy beverage products, dietary supplement products, so-called “functional foods,” and other natural health products.

In one of the field project areas in Shaanxi, there is a local wine-making facility where an entrepreneur is building a new business on the production of wines made from local wild-harvested southern schisandra. At this facility, annual production is estimated at 100 tons of wine. The current annual demand for southern schisandra for this level of production is about 10,000 kg dry weight. The wine-maker believes that this production level is low because their marketing efforts are presently limited to only the local market and tourist season market. He envisages a scale up by about 10 times, eventually with an annual demand requirement of 100,000 kg southern schisandra from the local wild harvesters.

Southern Schisandra Harvest and Post-harvest Handling

Relevant for the wild harvesting of southern schisandra is the Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) for Chinese Crude Drugs, published in 2002 by the Chinese State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA).14 The SFDA GAP provides the basic principles for the production and quality management of Chinese crude drugs, including within its scope both cultivation and wild collection. Thus this GAP can serve as a general reference for harvest and post-harvest handling practices. The quality requirements specified in the PPRC monograph must also be taken into consideration prior to developing a southern schisandra wild harvest management plan. Additionally, the ECBP project has produced a draft Nanwuweizi Guidelines for Harvesters and Traders, which was tested during the autumn 2009 harvest.

Southern schisandra should be collected in the autumn when the fruits reach full size. Depending on the weather, this could be from August to October. The immature green fruits that occur earlier in the mid- to late- summer should be left to ripen, but they need to be picked just before they turn bright red. Bright red fruits tend to rot when sun-dried, which is why fully-formed, pale green to pink-colored fruits are collected and then dried.

The person responsible for the collection operation must be qualified to identify and differentiate the correct species from other related species that may look similar and/or also occur in the same collection areas. There are 39 species and 2 genera (Schisandra and Kadsura) in the family Schisandraceae. Only one Schisandra species is indigenous to North America, but China has 27 species, 16 of them endemic. The flowers are either staminate or pistillate, and distinctive ripe red fruits are common. Because of the number of other species that share the common name nanwuweizi, confusion and misidentification are possible. (The PPRC monograph includes 3 methods for confirming the botanical identification of nanwuweizi, as well as an assay for quantifying the level of the relevant marker compound schisantherin A [C30H32O9].)

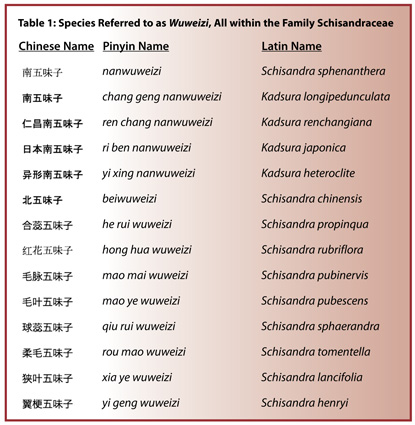

Table 1 shows the Chinese names, Pinyin transliterations, and corresponding Latin names for the various plants that are called wuweizi (the name wuweizi refers to the 5 flavors of the fruits). The reader should note that the first two listed share the same Chinese characters.

Because southern schisandra is a climber, the collectors only pick the more accessible fruits or use a hooked stick to reach mature clusters of fruit. Using hand-held picking shears, the harvester holds the cluster away from the vine and cuts it with part of the stem still attached. The cut clusters are placed into clean picking bags, baskets, or harvest trays. The fruits can be sun-dried or dried on trays in an oven. If sun dried, the fruits are generally removed from the stalks and are spread out evenly on clean drying screens or racks, underneath a canopy that prevents contamination from birds and/or wetting from rainfall. Drying frames are placed above the ground, for example on racks (for adequate air circulation).

If the southern schisandra is dried on trays in a drying oven, the temperature, duration, and air circulation must be controlled. The final moisture content of dried southern schisandra should range from 8% to not more than 10%.

After drying, cleaning and additional grading steps are carried out to remove all foreign matter that could lower the quality and market value. Any remaining stalks are removed from amongst the dry southern schisandra fruits. The next step is to use sieves, grading tables, or screens in order to eliminate foreign matter such as adhering dirt or other plant parts (such as the receptacle and peduncle), as well as substandard or immature green fruits.

Nanwuweizi Quality Standards

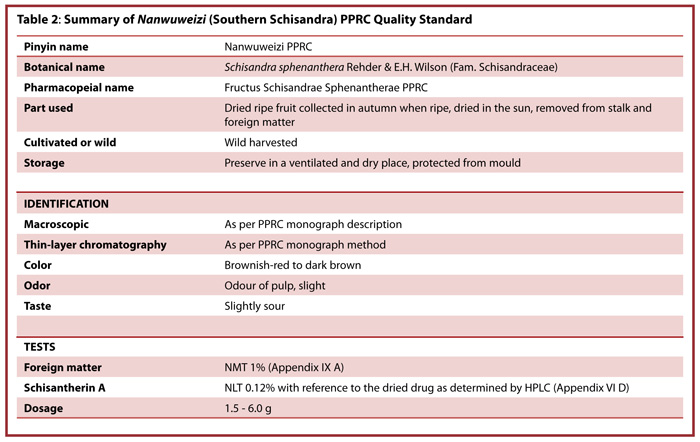

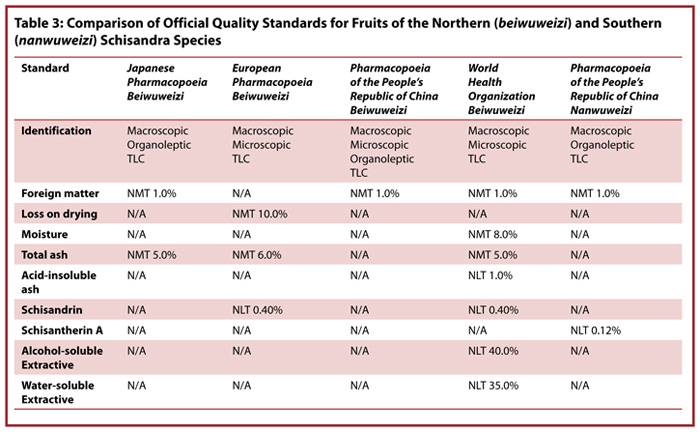

Official quality standards or acceptance criteria for the test and release of the herbal drug southern schisandra fruit for use in medicinal products have been published in the currently valid edition of the PPRC.9 Table 2 summarizes the PPRC standards for pharmaceutical quality nanwuweizi. Table 3 shows a comparison of the official quality standards for nanwuweizi against those for northern schisandra fruit (beiwuweizi), excerpted from the following compendia: Japanese Pharmacopoeia (JP XV 2007),15 European Pharmacopoeia (PhEur 6.3 2009),16 PPRC (English Edition 2005), and World Health Organization’s WHO Monographs on Selected Medicinal Plants, Volume 3.17 (This table includes only the monograph-specific standards and not the purity standards for microbiological quality, pesticide residues and heavy metals that are generally applicable for all herbal drugs in the pharmacopeias.)

Producer Associations: Coordination and Supply Chain Capability

Developing and maintaining market share is not just an issue of quality. What is also required is to get sufficient quantity to the market, on time, at the right price. Wild harvest certainly offers opportunities, but harvesting in sufficient quantity to meet market demand may require hundreds of rural harvesters to collect specific products. This will be the case for southern schisandra fruits if market expectations are met. What is required are well established and effective local institutions using communications technologies such as mobile phones to coordinate “bulking up” of resources, reduce transport costs, and improve supply chain capability. For this reason, the ECBP project has established local producer associations in order to reduce the high transaction costs of coordinating hundreds or—as this project “scales up”—thousands of smallscale producers to get sufficient quantities of TCM plant products harvested and ready for the market at the right quality.

Southern Schisandra Branding, Marketing, and Trade

The market for this species exists within 2 growing national and international industries: the energy drinks sector and the schisandra herbal tea market. There are also extraction houses producing aqueous extracts, aqueous-alcoholic extracts, and CO2 extracts of southern schisandra for use in cosmetics and dietary supplement products (e.g. Draco Natural Products, Shanghai, PRC, and Flavex® Naturextrakte GmbH, Rehlingen, Germany). All of these offer an opportunity of “Panda friendly” branding, linking to one of the world’s most iconic animals and to certified production from managed wild harvest. This ECBP project has started with partnerships linked to markets in Europe and North America, where there is more interest in southern schisandra than there presently is in the Chinese market, which values northern schisandra more than its southern “Cinderella” cousin. China’s energy drink sector, however, is a growing market (with 55% annual growth),18 so southern schisandra could become incorporated more extensively into the Chinese market through these products. The energy drink sector has already generated a huge global market for seed extracts from the netotropical plant guaraná (Paullinia cupana, Sapindaceae);19 whether schisandra follows the same trajectory remains to be seen. But if commercial markets develop, then attention has to be given to sustainable wild harvest and production in agroforestry systems in the Upper Yangtze ecoregion.

The Future

Any successful business needs careful planning based on realistic advice and partnerships between multiple stakeholders. Developing sustainable “green businesses” in remote areas for an international market is particularly challenging. Based on the experience of this article’s authors, it is strategic to focus international enterprise development efforts on one “winning” species first, then other species can follow at a faster pace based on the ability to produce them at good quality, in sufficient quantity, on time, and at the right price. Although the southern schisandra trade will start with sales to conventional markets, there is potential for launching products certified as organic wild (according to USDA’s National Organic Program Wild-crop Harvesting Practice Standard) and/or FairWild® (according to the standard of the FairWild Foundation) produced in the project pilot-study sites, and to later expand production to other villages.

Despite many obstacles, including a major earthquake, this ECBP project, coordinated through WWF-China’s Chengdu office, now has a solid basis for linking sustainable harvest to “green” business. The ECBP project in the Upper Yangtze ecoregion is developing partnerships to enhance the opportunities for small-scale producers, enabling businesses, local government, and producers’ associations to work together in a multi-stakeholder process.

The biggest challenges are to connect with the right players who will be supportive, avoid “elite capture,” and avoid growing too quickly, in case this compromises product quality and sustainable harvest.

For the autumn 2009 harvest, 2 herbal companies, one a certified organic and kosher extraction house in the PRC (Draco Natural Products, Shanghai) and the other a finished herbal product manufacturer in the United States (Traditional Medicinals®, Sebastopol, CA), have jointly agreed to give the project a boost by ordering up a sufficient amount of dried fruits through the newly established Shuijing TCM Producer Association to produce a pilot production batch of concentrated dried extract. The American company will purchase the extract and evaluate it for potential use in one of its products. If the trial production run meets expectations, significant scaling up for a larger 2010 harvest is envisaged, as well as the start of a long-term sustainable trade relationship that will bring additional income to the villagers in the ECBP project areas while contributing to the conservation of wild populations of medicinal plants.

Anthony (Tony) Cunningham is an ethnoecologist working with People and Plants International and an adjunct professor at the School of Plant Biology, University of Western Australia.

Josef Brinckmann is the vice-president of Research & Development at Traditional Medicinals, Inc. in Sebastopol, California and a member of the Advisory Board of the American Botanical Council.

*The Harmonized Commodity Description and Coding

System, generally referred to as “Harmonized System” or simply “HS,” is

a multipurpose international product nomenclature developed by the

World Customs Organization (WCO). It comprises about 5,000 commodity

groups, each identified by a 6-digit code, arranged in a legal and

logical structure and is supported by well-defined rules to achieve

uniform classification. The system is used by more than 190 countries

and economies as a basis for their Customs tariffs and for the

collection of international trade statistics. Over 98% of the

merchandise in international trade is classified in terms of the HS.

†Qi in TCM is the basic element of energy that makes

up the human body and supports the vital activities. It circulates in

the channels and collaterals. Deficiency of qi relates

to decreased functional activity, usually manifested by lassitude,

listlessness, shortness of breath, spontaneous sweating and weakened

pulse. Since each internal organ has its own functional activities,

deficiency of qi of different organs may have different manifestations. Herbal drugs to reinforce qi are used for cases of qi deficiency.

‡Kidney in TCM does not correlate with the “kidneys”

in Western anatomy. It is defined as an internal organ that stores the

essence of life either congenital or acquired (from food) for growth

and development, as well as semen for reproduction. It controls urine

elimination and water metabolism and helps the lung in accomplishing respiration.

§Internal heat in TCM is a (1) heat syndrome caused by consumption of yin or

body fluid, usually manifested by fever in the afternoon or at night;

heat sensation in the chest, palms, and soles; night sweating; thirst;

constipation; reddened tongue with scanty coating; and thready, rapid

pulse; or (2) invasion of exogenous pathogenic heat into the interior

of the body.

References

- Leakey RRB, Newton AC. Domestication of ‘Cinderella’ species as the start of a woody-plant revolution. In: Leakey RRB, Newton AC (eds.). Tropical Trees: Potential for Domestication and the Rebuilding of Forest Resources. London, UK. HMSO. 1994c;3-5.

- Experts estimate over $75 billion economic loss from Sichuan earthquake. The Epoch Times. May 26, 2008. Available at: http://en.epochtimes.com/ news/8-5-26/71022.html. Accessed December 26, 2008.

- Cunningham T. EU China Biodiversity Programme: Preparation for establishing certification and monitoring systems. Supporting the sustainable management of traditional medicinal plants in high biodiversity landscapes of the Upper Yangtze ecoregion. Beijing, China: WWF-China, EU-China Biodiversity Programme, UNDP China. December 2008 [internal report].

- Scheid V. Shaping Chinese medicine: two case studies from contemporary China. In: Hsu E (ed.). Innovation in Chinese Medicine. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. 2001;370-404.

- Vines G. Solving Chinese puzzles. Kew Summer. 2008;18-21.

- Brinckmann JA. China and other East Asian countries. In: Market News Service for Medicinal Plants & Extracts. Geneva, Switzerland: International Trade Centre (ITC) / UNCTAD / WTO. June 2008; Number 27;16-18.

- Phillip Securities Research. Stock Update—Eu Yan Sang International Ltd. January 17, 2003;1-3.

- Chen S. Sustaining herbal supplies: China. In: United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Sharing Innovative Experiences: Examples of the Development of Pharmaceutical Products from Medicinal Plants. New York, NY: UNDP Special Unit for South-South Cooperation; Trieste, Italy: Third World Network of Scientific Organizations (TWNSO). 2004; Volume 10. Available at: http://tcdc.undp.org/sie/experiences/vol10/V10_S4_ herbalSupplies.pdf.

- Pharmacopoeial Commission of the PRC. Fructus Schisandrae Chinensis and Fructus Schisandrae Sphenantherae. In: Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China, English Edition 2005. Beijing, China: People’s Medical Publishing House. 2005;109-111.

- Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC) European Medicines Agency (EMEA). Reflection paper on the adaptogenic concept. London, UK: European Medicines Agency. May 8, 2008.

- Huyke C, Engel K, Simon-Haarhaus B, Quirin KW, Schempp CM. Composition and biological activity of different extracts from Schisandra sphenanthera and Schisandra chinensis. Planta Med. 2007;73:1116-1126.

- Xin HW, Wu XC, Li Q, et al. Effects of Schisandra sphenanthera extract on the pharmacokinetics of tacrolimus in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64(4):469-475.

- Xin HW, Wu XC, Li Q, Yu AR, Xiong L. Effects of Schisandra sphenanthera extract on the pharmacokinetics of midazolam in healthy volunteers. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67(5):541-546.

- State Food and Drug Administration (SFDA). Good Agricultural Practice (GAP) for Chinese Crude Drugs. (Interim). Beijing: People’s Republic of China (PRC): State Food and Drug Administration. June 1, 2002.

- Japanese Pharmacopoeia Commission. Schisandrae Fructus. In: The Japanese Pharmacopoeia (JP) fifteenth edition 2007. Tokyo, Japan: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare. 2007;1352-1353.

- European Pharmacopoeia Commission. Schisandrae chinensis fructus. In: European Pharmacopoeia, sixth edition, third supplement. Strasbourg, France: European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and Healthcare. 2009;4288-4289.

- World Health Organization. Fructus Schisandrae. In: WHO Monographs on Selected Medicinal Plants, Vol 3. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization. 2007;296-313.

- Reissig CJ, Strain EC, Griffiths RR. Caffeinated energy drinks—a growing problem. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;99-1-10.

- Smith N, Atroch AL. Guaraná’s journey from regional tonic to aphrodisiac and global energy drink. eCAM Advance Access. December 5, 2007. doi:10.1093/ecam/nem162. Accessed: August 28, 2009.

|