Issue:

97

Page: 46-57

Echinacea Differences Matter: Traditional Uses of Echinacea angustifolia Root Extracts vs. Modern Clinical Trials with Echinacea purpurea Fresh Plant Extracts

by Francis Brinker

HerbalGram. 2013; American Botanical Council

Editor’s note: This article is based on a prior version published in the International Journal of Naturopathic Medicine, Vol. 5, Issue 1, 2012. This version has been enhanced with additional text and table notes, modified for HerbalGram style, and peer-reviewed by experts in the field.

Introduction

Circa 1900, the reputation of echinacea among Eclectic physicians* was built on the common use of high-alcohol extracts of Echinacea angustifolia (Asteraceae) roots applied topically for wounds, infections, and poisonous bites and stings, and administered internally for acute infections now known to be bacterial. Beginning in the mid-20th century, European clinical research on plant preparations of fresh aerial E. purpurea plant juice, preserved with 22% ethanol or the whole plant extracted with 65% ethanol, established its usefulness in treating the common cold. Thus, the perception of Echinacea spp. root extracts was transformed based on their generic relationship. The proclivity of modern botanical use for evidence-associated applications has led to widespread confusion regarding the differences between these distinct botanical species and their preparations.

Original Eclectic Preparations and Official Recognition

Dr. H.F.C. Meyer of Nebraska was the first to produce a commercial extract of echinacea. Although usually combined with about one-eighth part each of hops (Humulus lupulus, Cannabaceae) and wormwood (Artemisia spp., Asteraceae) — plant parts not specified — in his Meyer’s Blood Purifier for internal use, he used the tincture of E. angustifolia root for local applications (either externally or internally to mucosa in the nose, mouth, and rectum).1,2 In 1887, Meyer and Dr. John King2 described Meyer’s use of the root for 16 years as an “alterative”† and antiseptic in the Eclectic Medical Journal, claiming that the tincture was effective internally and externally for treatment of boils, carbuncles, ulcers of the throat and extremities, hemorrhoids, and wasp and bee stings. In 613 cases of rattlesnake venom poisoning treated in humans and animals, most recoveries occurred in two to 12 hours.

By 1900, most Eclectic physicians were using Lloyd Brothers Pharmacists’ E. angustifolia extracts, following years of study by J.U. Lloyd.1 After privately supplying a tincture of E. angustifolia root to Eclectic investigators beginning in 1890, in 1894 the Lloyd brothers introduced their commercial Specific Medicine Echinacea to the medical profession.3,4 J.U. Lloyd determined that the characteristic acrid principles of the dried root that produced a tingling and numbness of the tongue required a high-alcohol concentration for extraction.1 By 1906, the use of echinacea as an external and internal remedy had extended to conventionally trained physicians. It also was being used by them for the treatment of infected wounds, septicemia, and poisonous insect bites and stings.5

The Lloyd Brothers Pharmacists manufactured various E. angustifolia preparations. Their Specific Medicine Echinacea with 65% alcohol (ethanol) had the same drug strength as a fluid extract (1:1), but its production involved a proprietary process.6 Other Lloyd brothers preparations included Echafolta, a refined preparation free of sugars and coloring matter and made with 92% alcohol. Considered equivalent to Specific Medicine Echinacea, Echafolta was the preferred choice in surgical cases, where greater cleanliness was desired.1,6 By 1922, a small quantity of iodine tincture had been added to Echafolta, causing it to be reserved for external use only.7 Echafolta Cream provided the active principles in a bland petrolatum base.8 It was used locally as a soothing dressing and as an adjunct to internal medication and surgical measures.1,6 A nonalcoholic extract of E. angustifolia for hypodermic use was given the trade name Subculoyd Echinacea.4 While occasionally specifying the specific type of preparation, most physician reports of E. angustifolia root extracts refer to whatever preparation was used simply as “echinacea.”

The Lloyd brothers emphasized the quality of their product as follows:

Echinacea is made from the carefully selected, prime, dried, cured, and assayed root of E. angustifolia. The quality of but few drugs is more influenced by conditions prevailing in different localities and by treatment during drying, than is Echinacea…. Prime drug from favored geographic regions may be ruined by careless or faulty manipulation…. The famous Lloyd process permits the extraction of delicate and complex botanical therapeutic principles without harm.8

The Lloyd brothers’ ongoing laboratory research led to their 1923 statement that “the therapeutic importance of the acrid constituent emphasized in our former literature constitutes but a part of its qualities, being most pronouncedly supported by less sensible constituents.”3

American Medical Association Condemnation Despite Acceptance by Physicians and the National Formulary

In 1909, a report by the Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry in the Journal of the American Medical Association condemned Dr. Meyer’s “absurd” claims and those “made on no better basis than that of clinical trials by unknown men who have not otherwise achieved any general reputation as acute, discriminating and reliable observers.”9 The report declared that “Echinacea is deemed unworthy of further consideration until more reliable evidence is presented in its favor.”9

Dr. Finley Ellingwood, the Eclectic materia medica professor at Bennett Medical College in Chicago, Illinois, responded to the Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry with the following:

Not a single member was engaged in active medical practice or was in a position to observe the action of drugs in the influence they exercise in the cure of disease…. In view of the fact that 20,000 physicians of the United States are using this remedy with success; and in view of the fact that there is a perfect agreement concerning the observations made by these reliable and trustworthy practitioners, … it seems strange indeed that this half dozen or more men should say that because of the scrutiny (or lack of scrutiny) that had been made, the remedy is deemed unworthy of further consideration.10

Clinicians remained enthusiastic about the usefulness and efficacy of echinacea after the condemnation published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. A survey was sent by the Lloyd brothers to more than 30,000 physicians who graduated from an array of medical schools, asking them to indicate which botanical drugs they used in their practices. More than 10,000 responded, and Echinacea ranked eleventh (listed by 5,065 physicians) in importance among all botanical drugs, as published in 1912 in the Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association.11

In 1916, the fourth edition of the National Formulary,12 published by the United States Pharmacopeia, established E. angustifolia dried roots and its fluid extract as official remedies. In testing the manufacture of a standard echinacea fluid extract in 1911 for inclusion in the National Formulary, it was concluded that menstruums with less than 67% ethanol did not adequately extract from the dried root those pungent principles responsible for the tingling sensation in the mouth (now known as alkamides).13

Early Scientific Assessments of E. angustifolia Root Extracts

The first major clinical research performed with E. angustifolia was conducted from 1913 to 1916 by Dr. V. von Unruh, a United States Army lieutenant. He used the nonalcoholic injectable medications Subculoyd Echinacea and Inula Compound (1.0 and 1.33 mL, respectively, intramuscularly or intravenously; Inula Compound also contained an extract of the root of elecampane [Inula helenium, Asteraceae]) in the treatment of patients with tuberculosis. Among 150 patients, he described 100% recovery in those with incipient pulmonary disease, 50% arrest in those with moderately advanced disease, but no success in those with advanced disease.14,15 In microscopic research involving more than 500 differential and cell counts carried out over more than four years, he found that injected Echinacea extract raised the opsonic index (making bacteria more susceptible to phagocytosis), increased the phagocytic power of leucocytes (allowing white blood cells to more readily engulf bacteria), improved leukopenia and hyperleukocytosis (helping normalize insufficient and excessive numbers of white blood cells), and normalized the percentage of mature neutrophils (balancing the number of the primary phagocytes for infections).15

Couch and Giltner subsequently tested the major echinacea products in animals.16 Performing injections in relatively small numbers of guinea pigs, they used bacterial toxins to experimentally induce tetanus and botulism, rattlesnake venom to simulate snakebites, and live bacteria to cause tuberculosis, dourine (a type of chronic venereal disease in animals), anthrax, and septicemia. Control animals were untreated or were administered the same alcohol content as in the extracts. Echinacea preparations (Specific Medicine Echinacea, Subculoyd Inula and Echinacea, or Echinacea fluid extract [National Formulary, 4th ed.]) were administered orally or parenterally before and/or after the pathologic injections. The induced diseases were interpreted as essentially the same in the control and treated animals. The authors concluded that the echinacea preparations were not of value in the treatment of diseases produced by microorganisms or biologic toxins.17,18

A 1921 editorial review of these findings published in the Journal of the American Medical Association noted:

“Of course, it will be retorted that the negative results on laboratory animals need not necessarily apply to sick human beings, and that subtle potent effects are not always discovered by research workers… Scientific medicine of today, however, asks for evidence that can be demonstrated by the pharmacologist or can be appreciated and accepted by the critical clinician as well as the quack.”16

The authors argued that the Echinacea fluid extract used in the experiment should be removed from the National Formulary.16

The same year, James Beal19 — director of pharmaceutical research at the University of Illinois, Urbana, and former editor of the Journal of the American Pharmaceutical Association — published a critical response to the laboratory research. He noted that the experiments were too few to be conclusive and that the results were not interpreted from a clinical perspective. Three times the minimum fatal dose of tetanus was administered to 19 animals receiving Specific Medicine Echinacea; 10 times the minimum fatal dose of botulinus was administered. The septicemia and dourine produced by Bacillus bovisepticus and Trypanosoma equiperdum, respectively, were species that were unassociated with human pathologic conditions. He further noted that, in the tuberculosis experiments, the mean weight loss in control animals was 129% that of the treated animals, which survived 36% longer. Of the animals injected with rattlesnake venom, the three controls died, while one of the six echinacea-treated guinea pigs survived.19

Responses of Clinical Empiricists

The Lloyd brothers, as a courtesy to Couch and Giltner and in fairness to all concerned, publicized their experimental results and suspended advertisements of echinacea preparations for one year, despite the fact that echinacea products were their best-selling botanicals from 1885 to 1921.17,18 Following publication of the 1921 negative laboratory research, the Lloyd brothers recorded their best sales of echinacea extracts by even larger margins over other botanicals. In 1922, echinacea sales increased again, almost 25 percent above the previous year’s sales and more than three times more than sales of the second-ranked plant drug, fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus, Oleaceae), among their 239 different plant remedies.3

In another attempt to assess the value of echinacea, the Lloyd brothers sent a postcard questionnaire to physicians concerning the use of echinacea preparations in their clinical practice in 1921. They asked for the physicians’ prominent indications and uses of echinacea, providing one line for the response and two additional lines for remarks. Physicians were asked to consider whether they would be willing to use a synthetic or other substitute to replace echinacea. In 1923, the responses were published.3 This unparalleled document provides ardent empirical consensus to support prior clinical claims.

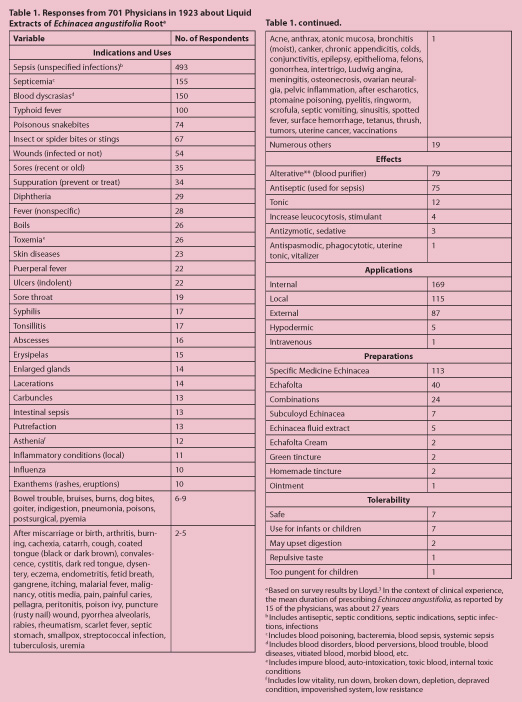

In comments received from 701 physicians who used E. angustifolia preparations in their practices, 70.3% (493 respondents) advocated its general use in septic conditions, 22.1% (155 respondents) specified its effectiveness in cases of septicemia or blood poisoning, and 14.3% (100 respondents) noted its efficacy for treatment of typhoid fever (Table 1). Use in cases of blood “dyscrasias” — a morbid imbalance of component elements; as used by Eclectics (see footnote ‘d’ in Table 1), this is considered descriptive of blood disorders, blood perversions, blood trouble, blood diseases, vitiated blood, morbid blood, etc. — by 21.4% (150 respondents), and as an alterative by 11.3% (79 respondents) were cited as other major indications. J.U. Lloyd3 noted that neither tetanus nor botulism was mentioned in any of the survey responses, nor had treatment with echinacea been recommended for these conditions in major Eclectic texts, challenging the pertinence of the findings by Couch and Giltner.17,18 However, a striking feature of the survey results was that most indications mentioned by physicians for E. angustifolia root preparations were for bacterial infections while few mentioned viral or fungal infections.3

In the survey results, 31.5% stated explicitly (88 respondents) or implicitly (133 respondents) that no substitute for echinacea would be acceptable, while 1.5% of respondents indicated that they would use a substitute if it was shown to be equally as effective.3 The most preferred preparations were Specific Medicine Echinacea internally or locally by 16.1% (113 respondents), Echafolta Cream by 5.7% (40 respondents), injectable Subculoyd Echinacea by 1.0% (seven respondents), and the Echinacea fluid extract by 0.7% (five respondents). Internal use was specified by 24.1% (169 respondents), local use by 16.4% (115 respondents), and external use by 12.4% (87 respondents). The most common local conditions treated topically or internally were poisonous snakebites (10.6%, 74 respondents), insect or spider bites and stings (9.6%, 67 respondents), and wounds (7.7%, 54 respondents). In the published survey, a list of the responding physicians’ names was provided. They hailed from 41 of 48 states, plus Canada, Mexico, and New Zealand.

Clinicians were enthusiastic about echinacea (see “Representative Remarks by 100 Physicians About Liquid Extracts of Echinacea angustifolia Root From Survey Results by Lloyd,” available online at: http://cms.herbalgram.org/herbalgram/issue97/hg97-feat-echinacea.html). In 1924, sales of echinacea products were seven times greater than those of any other product made by the Lloyd Brothers Pharmacists.20 To keep the use of echinacea in context, the Lloyd brothers described the therapeutic rationale for its application as follows: “Echinacea is a useful aid in the treatment of infection and sepsis, local or systemic… It is employed as an aid where there is a necessity for agents that possess general antibacterial properties.”8

Medical Use of E. angustifolia Root Extracts for Respiratory Infections

Notably, when E. angustifolia was first introduced to clinical medicine in the late 19th century, scant mention was made of its use in treating simple upper respiratory tract infections. In 1898, Felter and Lloyd1 noted that E. angustifolia hydroalcoholic extract contributed much to the cure of catarrh of the nose, nasopharynx, and respiratory tract. In a 1919 summary by the Lloyd brothers21 of reports from 1,000 physicians asked to cite the most important flu remedy following the recent influenza pandemic, echinacea was not listed among the nine most useful remedies for influenza or pneumonia, or among the nine best external applications for either of these conditions. Echinacea was noted in passing by some physicians who listed it when certain remedies were most indicated, for example, “where sepsis is marked, Echafolta or Echinacea becomes most important.”21

That same year (1919), when E. angustifolia extracts were recommended by Ellingwood22 for catarrhal conditions, it was cited both as an internal and as a local medication. In the survey responses from 701 physicians published by J.U. Lloyd3 in 1923, 10 respondents mentioned influenza as a prominent indication for use of echinacea, while only two specified its use for catarrh and one specified it for colds.

The use of echinacea extracts for treating influenza was discussed in 1929 by H.T. Cox,23 who believed (as is the general consensus today) that early application of “good-sized doses” from the first day until the body temperature reached normal was the best means of using this remedy. However, even after several days of influenza, echinacea in “large enough dosage” still was used persistently. In patients with purulent expectoration, the dosing continued until the sputum cleared. Echinacea angustifolia was prescribed along with appropriate cough preparations until the pulmonary congestion was entirely resolved. Large doses (the author again referred to “good-sized doses”) were administered to patients with influenza until the cough subsided.

Eclectic Human Research and Decline

Preliminary human research was attempted in 1934, when students at the Eclectic Medical College in Cincinnati, Ohio, volunteered as subjects to study the effects of echinacea by taking therapeutic doses for four days. Specific Medicine Echinacea was administered in water in doses of two-to-15 minims, derived from two-to-15 grains (130-975 mg) of the dried root. Blood samples were drawn at baseline and again after each day of use. Increases in total leukocyte counts were apparent, peaking in two-thirds of the subjects after 24 hours and in the remaining one-third after 48 hours.24 The leukocyte increase was mostly neutrophils after 24 hours and mostly lymphocytes after 48 hours. Total and differential counts were normal after 72 hours. These uncontrolled results, crude by modern standards, suggest that echinacea combats infectious agents acutely, briefly, and indirectly through the blood.

Echinacea angustifolia use diminished after the decline of Eclectic medicine in the late 1930s. This was indicated by the dropping of Echinacea fluid extract from the eighth edition of the National Formulary25 in 1946, although the dried roots entry appeared in this official text that year for the last time. In 1950, in an attempt to identify direct antibacterial activity, German researchers isolated the caffeic acid derivative echinacoside from the root, which demonstrated weak inhibition of streptococcal and Staphylococcus aureus gram-positive bacteria.26

Adoption by Naturopathic Physicians

Echinacea angustifolia was prescribed by early naturopathic physicians for local and internal use in accord with the indications established by the Eclectics. Echinacea was considered one of naturopathy’s most valuable herbs. In 1936, Specific Medicine Echinacea was recommended by naturopathic physicians as an alterative for septic conditions.27 In such cases, 20 drops of Specific Medicine Echinacea in a little water every four hours was suggested for treatment of recurring boils, carbuncles, ulcerations, and lymphangitis (inflamed lymphatic vessels). Septic fevers, typhoid fever, and acute nephritis were treated with 20 drops every two hours until the crisis passed. This preparation was to be administered internally and applied locally as a wet dressing for snakebites, cuts, wounds, and insect stings.

Twenty years later, the Echinacea fluid extract was advocated again in a naturopathic journal as a treatment for septicemia, as an antiseptic for boils, and as a local application for swelling.28 A tincture of the fresh root (one teaspoonful every two-to-four hours) was recommended in patients with diphtheria and puerpural septicemia. It was often combined with other appropriate remedies.28,29

In 1953, the Naturae Medicina and Naturopathic Dispensatory recommended hydroalcoholic extracts of the dried root of E. angustifolia, along with its water-based decoction, as “one of Naturopathy’s most faithful antibiotics and alteratives.”29 Internal use of the tincture or Specific Medicine Echinacea, together with its external application, was emphasized again for insect stings, boils, carbuncles, and certain septicemias. The tincture or decoction was used as a gargle for buccal ulcerations, ulcerative stomatitis, gingivitis, tonsillitis, pharyngitis, and as a retention colonic for ulcerative colitis. In a mixture with glycerin, it was applied on a tampon for eroded cervix and nonspecific vaginitis with leucorrhea.29

Notable natural medicines excluded from this compendium29 were opiates and antibiotics. The absence of antibiotics is particularly noteworthy because their use had been addressed positively by John Bastyr, the renowned naturopathic physician, in an article in the Journal of the American Naturopathic Association in 1950.30 He discussed in detail the use of penicillin, streptomycin, aureomycin, bacitracin, polymyxin, neomycin, terramycin, and others. These products were considered by Dr. Bastyr to be appropriate for use on a selective basis, being derived from lower plant life forms according to the taxonomic classifications of that time.

Naturopathic physicians treated many infectious diseases without modern antibiotic medicines. This was primarily due to the disruptive effects that these powerful medicines had on symbiotic bacteria in the intestines. Natural methods of destroying germs and stimulating natural immunity were used preferentially.31 Dr. Bastyr30 specifically noted the antibacterial efficacy of allicin from garlic (Allium sativum, Liliaceae) and extracts of sagebrush (Artemisia tridentata, Asteraceae), juniper (Juniperus communis, Cupressaceae), and buttercups (Ranunculus spp., Ranunculaceae), when prescription antibiotics were inappropriate or if a change of therapy was required.

Dr. Bastyr also used E. angustifolia root tincture internally for the treatment of septicemia, pyuria (pus in the urine), and gangrene.32 He administered it to treat coughs and colds, and to boost deficient immune function in many infections. For the treatment of infections, echinacea was used frequently in combination with other immune-enhancing and antimicrobial botanicals. A fundamental formula used by Dr. Bastyr combined four parts E. angustifolia root extract, four parts goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis, Ranunculaceae) rhizome extract, and one part poke (Phytolacca americana, Phytolaccaceae) root extract. He also spoke highly of adding wild indigo (Baptisia tinctoria, Fabaceae) root to this formula. He often would combine five parts echinacea with one part wild indigo for infections, and administer 60 drops three times daily. He used diluted echinacea extract topically to treat decubitus ulcers as well.

A modern E. angustifolia fresh root (1:1) 65% ethanol extract (Specific Echinacea Extract, Eclectic Institute, Inc.; Sandy, Oregon [manufactured using the Lloyd extractor]) administered orally to six male rats in their drinking water for six weeks recently was shown to increase the initial antigen-specific day 0 induction of immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody response after seven days and subsequent day 10 antigen inductions of IgG on days 14, 21, 24, and 27, in a statistically significant manner compared with four control rats (range, P=0.04 to P=0.002).33 Non-significant IgG increases also occurred on days 10, 18, and 32, but not after the third antigen challenge on day 35. Although increases in antigen-specific immunoglobulin M occurred on all of the aforementioned days, as well as on days 35 and 39, none of these increases were significant compared with control animals. These results suggest that this fresh root extract may enhance subacute immune responses by increasing antigen-specific antibody production.

Introduction of Echinacea purpurea

Other Echinacea species (e.g., E. pallida root in the fourth [1916] and eighth [1946] editions of the National Formulary12,25) sometimes were used as substitutes for E. angus-tifolia.28 Echinacea purpurea was mentioned by Dr. John King in his Eclectic American Dispensatory (1853) as a remedy deserving “a full and thorough investigation from the profession;”1 at that time, E. purpurea also was known by the synonym Rudbeckia purpurea and occasionally was confused with E. angustifolia, although rarely used by the Eclectics.1

Echinacea angustifolia had been introduced into homeopathic practice in Europe in the late 19th century. Because of a severe shortage of this drug in Europe in the 1930s, the German phytopharmaceutical manufacturer Gerhard Madaus went to the United States to obtain seeds of E. angustifolia; however, he mistakenly bought E. purpurea seeds.34,35 Consequently, Madaus decided to extract the juice from the aboveground (aerial) part of the blooming E. purpurea plant.35 Preserved with 22% alcohol, E. purpurea plant juice with cichoric acid and water-soluble arabinoxylan and arabinogalactan polysaccharides is distinct from E. angustifolia root extracts in greater than 50% ethanol with echinacoside and is distinguishable from lipophilic alkamides.36 Because E. purpurea juice previously had not been used clinically, Madaus experimented with its use. Since then, much European research on Echinacea has used this preparation (Echinacin®, Madaus AG; Koln, Germany ) or similar preparations internally and externally.34-36

In the 1950s, the Swiss naturopath Alfred Vogel37 traveled to America and learned the native uses of E. angustifolia from Native Americans of the Lakota (Sioux) tribe in South Dakota. Finding that the related species E. purpurea was effective and easier to harvest, he returned with seeds of this species to cultivate in the Swiss “lowlands” at 4,500 feet above sea level (ca. 1,600 m). After 10 years, when these plants had acclimated sufficiently to produce flowers, he began using the tincture of the whole fresh plant to strengthen the immune response to infectious conditions. Vogel’s E. purpurea extract combines 95% aerial plant with 5% roots in 65% ethanol (Echinaforce®, Bioforce AG; Roggwil, Switzerland).

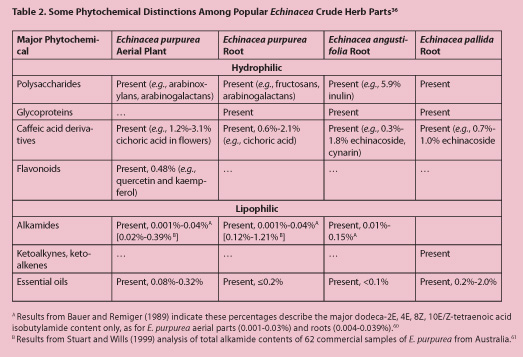

In 1989, the German Commission E officially approved the fresh-flowering E. purpurea aboveground plant and its preparations for “supportive treatment” of colds and chronic infections of the respiratory and lower urinary tracts, and, externally, for poor wound healing. In 1992, E. pallida fresh or dried root was recognized officially by the Commission E as supportive therapy in influenza-like infections, particularly the 50% alcoholic tincture. However, the roots of E. purpurea and E. angustifolia were not approved, due to lack of adequate clinical data available at the time.38 Echinacea purpurea, E. angustifolia, and E. pallida roots are phytochemically distinctive (Table 2).36 Surprisingly, although water extracts of E. purpurea roots were potent against influenza virus, and although ethanolic fractions and alkamides of E. angustifolia root inhibited rhinovirus in vitro, the E. pallida root water and ethanolic fractions were ineffective against both.39 European experience and clinical research with the cultivated E. purpurea plant led to its popularization in the current American marketplace.

Randomized and Controlled Therapeutic and Prevention Trials With Echinacea Extracts for Upper Respiratory Tract Viral Infections

Recent clinical trials of commercial E. purpurea fresh plant liquid preparations and extracts have been well publicized and consistently demonstrate efficacy against acute upper respiratory tract viral infections. A 2007 meta-analysis40 of 14 studies among various Echinacea products evaluated randomized, controlled trials that studied a total of 1,356 patients for incidence and 1,630 patients for duration of the common cold. It showed that the use of these preparations decreased the chance of developing a cold by 58% and reduced the duration by a mean of 1.4 days. The 14 preparations in the meta-analysis included seven from E. purpurea, four from a combination of E. purpurea and E. angustifolia, one from E. angustifolia only, one from E. pallida, and one from an unidentified species. Significant reductions in occurrence and duration of the common cold were observed based on a subgroup analysis limited to five E. purpurea aerial plant juice investigations.

A 2006 systematic review41 of 16 randomized, controlled trials for the common cold was performed for heterogeneous Echinacea preparations. In two prevention trials, 411 subjects received Echinacea products, while five trials involved self-treatment (1,064 subjects), and nine trials studied clinically treated upper respiratory tract viral infections (1,126 subjects). This review identified no preparation with evidence of benefits for prevention but concluded that preparations based on E. purpurea aerial parts may be effective for early treatment of colds. Because other preparations were not phytochemically comparable, variations in the studies provided no clear evidence of their efficacy.

The single, randomized, placebo-controlled, double-blind study42 of E. angustifolia performed using three noncommercial extracts of two-year-old fresh roots to prevent or treat colds induced by rhinovirus type 39 in 399 volunteers was possibly the most publicized investigation; this study was funded by the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), and results were published in the New England Journal of Medicine. These extracts, made with supercritical carbon dioxide, 60% ethanol, or 20% ethanol, produced no tendency toward improvement when used for one week after virus exposure. For volunteers treated one week before and one week after exposure, clinical colds developed in 50% of participants receiving the 20% ethanol extract, in 57% receiving the 60% ethanol extract, in 62% receiving the supercritical carbon dioxide extract, and in 66% receiving placebo. The mean total symptom score was 12.1 for patients receiving the 20% extract, 13.2 for those receiving the 60% ethanol extract, 15.5 for those receiving the supercritical carbon dioxide extract, and 15.1 for those receiving placebo. However, none of the differences were statistically significant compared with placebo.

This study42 has been criticized for insufficient dosage (900 mg of root extractives vs. recommendations of a daily dose of 3 g by the World Health Organization and the Canadian Natural Health Product Directorate), inadequate validation of species identity, and limitation to one of more than 100 subtypes of rhinovirus.43 However, the daily dose in an E. pallida study44 of 160 patients with flu-like infections was extracted from 900 mg of root, which significantly reduced the illness duration, symptom scores, and clinical scores compared with placebo.

Although two authors of the NIH study42 had previously acknowledged that the geographic location of growing E. angustifolia and the time of its harvest affect the chemical composition,45 neither of these factors was described in the 2005 study42 in characterizing the roots obtained from a German company (presumably cultivated in Europe). While the supercritical carbon dioxide extract contained 74% alkamides and no polysaccharides or caffeic acid derivatives, the 60% ethanol extract had an uncharacteristically high 49% total polysaccharides, 2.3% alkamides, and 0.16% cynarin.42 The 20% ethanolic extract with 42% polysaccharides and 0.1% alkamides contained no caffeic acid derivatives. The polysaccharide content was not profiled on the basis of molecular weight but only on relative monosaccharide content, which is of no real value.

The high polysaccharide content of the 60% ethanol extract and the low or 0% content of caffeic acid derivatives (especially echinacoside) in all three extracts suggest that the roots used were not equivalent to “wild-crafted” roots traditionally favored and now used in some commercial echinacea products sold in North America. However, whether or not the lack of efficacy of these experimental E. angustifolia root extracts against a single rhinovirus subtype is accepted as legitimate evidence of its clinical effect on the common cold, this application is not representative of the traditional empirical use of this species.

On the other hand, success for prevention of the common cold was shown over a four-month period in a large randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study published in 2012. A total of 355 patients took a liquid 57% ethanolic extract of the fresh E. purpurea aerial plant (95%) and root (5%) (Echinaforce®, Bioforce; Roggwil, Switzerland) versus 362 taking a placebo. A dose of 0.9 ml, three times daily (from 2,400 mg herb/day) was used, except during acute stage of colds that developed when the dose was increased to five times daily (4,000 mg/day). The extract was diluted in water and held in the mouth for 10 seconds before swallowing. Though the extract group had a history of significantly greater susceptibility to cold infections, it had significantly fewer cold episodes and episode days (each 26% less). Recurrent infections were significantly decreased with echinacea extract (59% less), while use of concurrent pain medications aspirin, acetaminophen, and ibuprofen were also significantly fewer with the extract (52% less). There were no significant differences between adverse effects or tolerability between the two groups over the four-month period, indicating safe long-term use.46

Contraindications and Potential for Drug Interactions

The German Commission E monographs38 for the approved E. purpurea herb and E. pallida root and for the unapproved E. purpurea root, E. pallida herb, and E. angustifolia herb and root, speculate that risks warrant avoidance of use in cases of systemic diseases such as tuberculosis, multiple sclerosis, leukosis, collagenosis, AIDS or HIV infection, and autoimmune diseases. These contraindications remain controversial, as they are theoretical and not based on any actual clinical data. Reactions may occur in allergic individuals, especially when aerial parts are used.47

Legitimate concerns about combining Echinacea species preparations with pharmaceutical drugs are also largely speculative and are based on in vitro research. For example, as a precaution, patients undergoing organ transplantation who take immunosuppressive drugs, such as cyclosporine, should avoid the use of Echinacea preparations or should consider short-term use.46 Echinacea purpurea root extract (oral dose of 1.6 g/day) for eight days increased the clearance and reduced the bioavailability of intravenous midazolam when this cytochrome P450 (CYP) 3A4 substrate was administered to 12 subjects; the same dose of E. purpurea root extract did not alter oral midazolam clearance, suggesting that some extract components inhibit intestinal CYP3A, while other absorbed components induce liver CYP3A.48 In a 15-day open-label trial with 15 HIV patients receiving antiretroviral treatment with darunavir/ritonavir, 500 mg of E. purpurea root extract (Arkocapsulas Echinacea, Arkopharma; Madrid, Spain) given every six hours for 14 days was well tolerated and did not significantly affect the drug pharmacokinetics.49 Echinacea angustifolia root tincture is a potent CYP3A4 inhibitor in vitro, more so than tincture of E. purpurea roots,50 but this has not been verified in human studies.

When an E. purpurea whole plant extract was given orally in a 1.6 gram daily dose to 12 healthy humans for 28 days, no significant effect on oral sedative midazolam was detected.51‡ An 8:1 extract of the whole fresh plant (Echinamide, Natural Factors Nutritional Products, Inc.; Everett, WA) was given in doses of 750 mg daily for 28 days to 16 healthy humans who were taking the antiretroviral combination drug lopinavir-ritonavir for 15 days prior and then 14 days with the extract. After the 14 combination days, there was no change in lopinavir bioavailability. After the extract had been administered for 28 days, single doses of fexofenadine and midazolam were administered; the midazolam bioavailability was significantly reduced, but fexofenadine pharmacokinetics were not significantly altered. This extract was shown to have a modest inducing effect on CYP3A as shown with midazolam, but not enough to counter the CYP3A inhibiting effect of ritonavir. It had no impact on P-glycoprotein efflux of fexofenadine.52

Most conventional pharmaceutical drugs, including the macrolide antibiotics clarithromycin and erythromycin, are metabolized by CYP3A4. A theoretical interaction between CYP3A4 substrates and E. angustifolia root tinctures is limited to in vitro data, while human research on the effects of E. purpurea root and whole plant extracts on this enzyme is equivocal; due to variations in preparations and outcomes, the current body of human research is too limited to predict pharmacokinetic or pharmacodynamic interaction outcomes with certainty, and little evidence exists to support significant clinical interactions with medications.53

Endangerment and Cultivation

The issue of sustainable harvest of wild-crafted E. angustifolia has been raised,54 yet it remains abundant in central Kansas, despite more than 100 years of commercial harvesting and digging booms.55 Because seeding in November yields the highest emergence for E. angustifolia plants in Nebraska,56 harvesting in the autumn and reseeding holes with the dry flower heads is a way to diminish loss from wildcrafting.

Echinacea angustifolia still grows over much of its historical range. Its global conservation status is ranked G4, i.e., “apparently secure.” In Kansas, where several generations of the same families have dug this species since the early 1900s, tagging pick-holes showed a regrowth potential of 36%, and measuring harvest density confirmed that the stands were not significantly diminished; areas that lay fallow for two-to-three years after harvesting allow more growth of the small roots and regrowth from remnants of larger harvested roots.57

Cultivation of Echinacea has increased rapidly because of the demand and its great value. Growth of the three major medicinal species, E. angustifolia, E. pallida, and E. purpurea, has been the most studied.58,59 Echinacea purpurea is easy to grow compared to the other two commercial species.59

Conclusions

The traditional clinical applications of E. angustifolia root hydroalcoholic extracts demonstrate their empirical usefulness. Simultaneous internal and local use was believed to increase efficacy. The historical use of E. angustifolia extracts to treat serious infectious diseases suggests that an advantage could be gained if they were given to complement conventional antibiotics. Clinical studies to investigate this possibility appear warranted, given the increasing incidence of antibiotic resistance.

However, positive evidence from clinical research on E. purpurea fresh plant liquid extracts for the treatment, and recently for the prevention, of upper respiratory tract viral infections has focused most attention in regard to commercial Echinacea species on this important use. Echinacea angustifolia also has been combined with E. purpurea in effective preparations for treating colds. Consequently, the recognition of E. angustifolia use for other infectious conditions has diminished, as conventional medicine inexorably depends on antibiotics.

Although sharing some similarities, selective use of Echinacea species, parts, and their preparations seems most appropriate for conditions established through empirical tradition (e.g., E. angustifolia root high-ethanol extracts internally and locally for treating sepsis, wounds, and bites) or through modern clinical research (e.g., fresh E. purpurea plant products for prevention and/or treatment of upper respiratory tract infections). The safety of Echinacea products is a major advantage, with few theoretical contraindications or individual allergic sensitivities. Echinacea popularity has resulted in regional overharvesting of wild E. angustifolia. Nonetheless, commercial cultivation of E. purpurea and conscientious wildcrafting can continue to provide a sustainable supply of these important botanical medicines.

Acknowledgment

Maggie Heran and her staff at the Lloyd Library and Museum in Cincinnati, Ohio, provided copies of archival material published by the Lloyd brothers.

Francis Brinker, ND, is a graduate of the University of Kansas, Kansas Newman College, and the National College of Naturopathic Medicine (NCNM). He has taught botanical medicine at NCNM, the Southwest College of Naturopathic Medicine, and the Arizona Center for Integrative Medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine. Dr. Brinker has written and edited numerous articles and monographs, and has authored six books on medicinal botanicals, including, most recently, Herbal Contraindications and Drug Interactions, 4th ed. He also has served as a consultant for Eclectic Institute, Inc., a manufacturer of herbal preparations — including several echinacea products — since 1986.

*Eclectic physicians were American reform physicians from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries who defied current medical conventions and incorporated in their practice any measures believed at the time to be clinically effective, especially by developing the application of native medicinal plants and their pharmaceutical preparations.

† The term alterative refers to an agent that “causes a favorable change or alteration in the processes of nutrition and repair, probably through some unknown way improving metabolism”7 or “medicinal materials that reestablish healthy function in various systems of the body.”32

‡ Characterization is obscure; on page 431 it states it was purchased from Wild Oats Markets, Inc. (Boulder, CO). There was no standardization claim. On page 435, it specifies the E. purpurea product is a whole plant extract.

Figure 1. Representative Remarks by 100 Physicians

About Liquid Extracts of Echinacea angustifolia Root From Survey Results by Lloyd3

- I use Echinacea locally as a wet dressing, and internally in all infections.

- My medicine case is not complete without Echinacea.

- I use Echinacea more than any other drug.

- I have had uniformly good results from use of Echinacea in all cases indicated.

- The greatest remedy that we have for sepsis.

- Dependable and safe.

- Echinacea is my first choice of drugs.

- There is no medicine in the materia medica that can take its place.

- Have used it successfully where all other remedies have failed.

- Locally, in infected wounds, I use 10 to 50% solution of Echinacea.

- Echinacea is the best all-around medicine in use.

- This [Specific Medicine Echinacea] has never failed me and until it does I intend to keep on using that preparation.

- There is no substitute for Echinacea, nor have I found any product as useful.

- Could hardly practice medicine successfully without Echinacea.

- I believe Echinacea is good in any trouble of the human.

- Could hardly get along without Echinacea in my practice.

- Echinacea has been tested “as if by fire.”

- The beneficial results I have obtained from Echinacea have not been equaled by other drugs in my practice.

- In spite of my endeavor to reduce the frequency of my use of Echinacea both internally and externally, I am still using more of it than any other remedy.

- I use large quantities of this drug, even give it in teaspoonful doses.… I should want to retain Echinacea if I had to give up all other remedial agents.

- Echinacea has never disappointed me in whatever case it was administered, either externally or internally.

- Echinacea is the best drug yet. It would take a book to tell its virtues.

- This plant and its preparations are great gifts of God.

- As years go on my satisfaction in the use of Echinacea increases.

- I use Echinacea in all septic cases, internally and externally. It has no equal.

- I always get favorable results when using Echinacea.

- I use Echinacea in so many different ways that I cannot well enumerate them.

- I simply must have Echinacea.

- Echinacea saved my own life.

- Echinacea is a remedy that grows upon any one who uses it, rather than diminishes.

- Genuine Echinacea is good enough. None other is so good.

- Conditions calling for Echinacea cannot be met successfully by substitutes.

- I know of nothing better.

- Echinacea covers a broader and more important field than any other drug in the Materia Medica. Experience and observation will prove this to any physician who uses it.

- Have defended the remedy many, many times.

- The greatest medicine.

- Would be lost without Echinacea.

- Never lost a case of typhoid fever in which I used Echinacea.

- If I could but have one drug to use, Echinacea would be my choice.

- Here Echinacea is first, last and always with me.

- Echinacea or nothing with me.

- It is unique.

- I use Echinacea externally and internally. There is no better drug.

- I consider it invaluable.

- If you have but one medicine for the whole family, give Echinacea.

- Its uses are too many to enumerate. I use Echinacea more than any other one remedy.

- Echinacea is one of the greatest medicines ever introduced.

- Echinacea is the best blood purifier in the world.

- I have great faith in the remedy.

- In these [septic conditions] I could not get along without Echinacea. It is invaluable.

- The more I use of it the better I like it.

- It is always dependable.

- I consider Echinacea one of the most useful remedies ever given to the profession.

- One of the great remedies in the Materia Medica.

- Echinacea is the best blood purifying agency in the Materia Medica.

- Every day calls for it.

- It is one of my big “universal” remedies.

- I consider Echinacea my best agent in snake and poisonous bites of all kinds.

- I consider Echinacea one of the best, if not the best, all-round remedy to be had, harmless but efficient.

- Large dose are best [for sepsis].

- Echinacea, used locally and internally, is in my experience the best single remedy in the Materia Medica to combat any septic condition.

- I find few conditions where Echinacea is not indicated.

- I could get along without any other one remedy better than without Echinacea.

- I use Echinacea daily, with full confidence.

- It is my sheet anchor.

- It is indispensable in all septic conditions.

- There is nothing better for cuts, stings, or bites of serpents.

- I use Echinacea in wounds to prevent or stop infection, and with absolute success.

- Echinacea is not with me [as] an experiment but a matter of fact.

- It should be in the hands of every physician.

- I prescribe Echinacea as frequently as any other single remedy. My work is surgical.

- In blood poisoning Echinacea has won for me many patients.

- Where other remedies fail Echinacea is sure to bring good results.

- Echinacea is included in nearly all my prescriptions. It seems a wonderful assistant to the indicated remedies.

- I am never out of Echinacea. I consider it one of the best remedies ever discovered.

- The good uses of Echinacea are too numerous to mention.

- Echinacea is one of the few remedies that always helps the patient.

- Echinacea has come to stay.

- There is absolutely no doubt in my mind as to the clinical value of Echinacea.

- Echinacea is in a class of its own.

- I don’t know how any doctor can get along without Echinacea.

- If it had not been for Echinacea, I feel that I would have been in my grave long ago.

- It is not antiseptic in the usual meaning of the word but it corrects septic conditions.

- I think the dose usually recommended is much too small. I give in urgent cases one-half teaspoonful Echinacea in water every one or two hours.

- Every physician should understand and use Echinacea.

- I use three times as much Echinacea as any other drug. I use it both locally and internally.

- Echinacea is “the best ever.”

- I have great confidence in Echinacea. My experience of many years constantly strengthens this confidence.

- I have used Echinacea in hundreds of cases and with the best results.

- I treat no infectious disease without this remedy, if I can obtain it.

- It saved my life.

- Echinacea never disappoints me except when my bottle goes dry.

- What object is there in anyone attempting to discredit Echinacea?

- I have found Echinacea one of the best baby and child medicines.

- I always keep an abundance of this remedy on hand.

- We do not yet know the half about Echinacea.

- In my opinion no other remedy contains equal curative properties.

- I get better results from Echinacea alone than from combinations.

- I am a believer in the use of Echinacea, externally, internally and eternally!

- In smallpox or other suppurative or eruptive manifestation, I use it locally, giving Echinacea, 3 parts; water, 1 part. Apply the mixture freely once each day.

References

- Felter HW, Lloyd JU. King’s American Dispensatory [originally published in 1898]. Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications; 1992.

- Meyer HCF, King J. Echinacea augustifolia [sic]. Eclectic Med J. 1887;47:209-210.

- Lloyd JU. Echinacea. Cincinnati, OH: Lloyd Brothers; 1923.

- Lloyd JU. A Treatise on Echinacea. Cincinnati, OH: Lloyd Brothers; 1917.

- Felter HW. Echinacea. Eclectic Med J. 1906;66:539-540.

- Anonymous. Dose Book. Cincinnati, OH: Lloyd Brothers Pharmacists, Inc; date unknown.

- Felter HW. The Eclectic Materia Medica, Pharmacology and Therapeutics [originally published in 1922]. Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications; 1994.

- Lloyd Brothers. Rationale of Therapeutic Use of Echinacea. Cincinnati, OH: Lloyd Brothers Pharmacists Inc; date unknown.

- Puckner WA. Echinacea considered valueless: report of the Council on Pharmacy and Chemistry [correspondence]. J Am Med Assoc. 1909;53:1836.

- Ellingwood F. Echinacea absolutely valueless? Ellingwood Ther. 1909;3:75-76.

- Lloyd JU. Vegetable drugs employed by American physicians. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash). 1912;1:1228-1241.

- Committee on National Formulary. The National Formulary, 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmaceutical Association; 1916.

- Beringer GM. Fluid extract of Echinacea. Am J Pharm. 1911;83:324-325.

- von Unruh V. Echinacea angustifolia and Inula helenium in the treatment of tuberculosis. Natl Eclectic Med Assoc Q. 1915;7:63-70.

- von Unruh V. Observations on the laboratory reactions in tests made of echinacea and inula upon tubercle bacilli and other germs. Ellingwood Ther. 1918;12:126-130.

- Anonymous. Echinacea. J Am Med Assoc. 1921;76:39-40.

- Couch JF, Giltner T. An experimental study of echinacea therapy. Am J Pharm. 1921;93:227-228.

- Giltner LT, Couch JF. Echinacea: a reply to Dr. Beal. Am J Pharm. 1921;93:324-329.

- Beal JH. Comment on the paper by Couch and Giltner on “An experimental study of echinacea therapy.” Am J Pharm. 1921;93:229-232.

- Zeumer EP. Echinacea locally. Eclectic Med J. 1924;84:23-24.

- Lloyd Brothers. Summary of reports from one thousand physicians. Ellingwood Ther. 1919;13:back cover.

- Ellingwood F. American Materia Medica, Therapeutics and Pharmacognosy [originally published in 1919]. Sandy, OR: Eclectic Medical Publications; 1994.

- Cox HT. Echinacea in influenza. Eclectic Med J. 1929;89:529-531.

- Ram NH. Echinacea: its effect on the normal individual–with special reference to changes produced in the blood picture. Eclectic Med J. 1935;95:34-36.

- Powers JL, chair. The National Formulary. 8th ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmaceutical Association; 1946.

- Stoll A, Renz J, Brack A. Isolation and constitution of echinacoside, a glycoside from roots of Echinacea angustifolia DC [in German]. Helv Chim Acta. 1950;33:1877-1893.

- Holmes ME. Echinacea augustiflora [sic]. Naturopath Herbal Health. 1936;41:17.

- Schramm A. Ehcinacea [sic]. J Naturopath Med. February 1957:15.

- Kuts-Cheraux AW. Naturae Medicina and Naturopathic Dispensatory. Des Moines, IA: American Naturopathic Physicians and Surgeons Association; 1953.

- Bastyr JB. Antibiotics. J Am Naturop Assoc. 1950;3:7, 13, 16-17.

- Koegler A. Can naturopathic medicine take the place of antibiotics? J Naturop Med. August 1959:11-13.

- Mitchell WA Jr. Plant Medicine in Practice: Using the Teachings of John Bastyr. Edinburgh, Scotland: Churchill Livingstone; 2003.

- Rehman J, Dillow JM, Carter SM, Chou J, Le B, Maisel AS. Increased production of antigen-specific IgG and IgM following in vivo treatment with the medicinal plants Echinacea angustifolia and Hydrastis canadensis. Immunol Lett. 1999;68:391-395.

- Parnham MJ. Benefit-risk assessment of the squeezed sap of the purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea) for long-term oral immunostimulation. Phytomedicine. 1996;3(1):95-102.

- Brown DJ. Herbal Prescriptions for Better Health. Rocklin, CA: Prima Publishing; 1996.

- Blumenthal M, ed. The ABC Clinical Guide to Herbs. Austin, TX: American Botanical Council; 2003.

- Vogel HC. The Nature Doctor. New Canaan, CT: Keats Publishing Inc; 1991.

- Blumenthal M, Rister R, Klein S, Riggins C. The Complete German Commission E Monographs –Therapeutic Guide to Herbal Medicines. Austin, TX: American Botanical Council; 1998.

- Hudson J, Vimalanathan S, Kang L, Amiguet VT, Livesey J, Arnason JT. Characterization of antiviral activities in Echinacea root preparations. Pharm Biol. 2005;43(9):790-796.

- Shah SA, Sander S, White CM, Rinaldi M, Coleman CJ. Evaluation of echinacea for the prevention and treatment of the common cold: a meta-analysis [published correction appears in Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:580]. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007;7:473-480.

- Linde K, Barrett B, Wolkart K, Bauer R, Melchart D. Echinacea for preventing and treating the common cold. Cochrane Libr. 2006;1:1-39.

- Turner RB, Bauer R, Woelkart K, Hulsey TC, Gangemi JD. An evaluation of Echinacea angustifolia in experimental rhinovirus infections. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(4):341-348.

- Blumenthal M, Farnsworth NR, Leach M, Turner RB, Gangemi JD. Echinacea angustifolia in rhinovirus infections. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(18):1971-1972.

- Dorn M, Knick E, Lewith G. Placebo-controlled, double-blind study of Echinaceae pallidaea radix in upper respiratory tract infections. Complement Ther Med. 1997;5:40-42.

- Dennehy C, Turner RB, Gangemi JD. Need for additional, specific information in studies with echinacea. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(1);369-370.

- Jawad M, Schoop R, Suter A, Klein P, Eccles R. Safety and efficacy profile of Echinacea purpurea to prevent common cold episodes: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Evid Based Compl Altern Med. 2012:841315. Epub [doi:10.1155/2012/841315], Sep. 16, 2012

- Mills S, Bone K. The Essential Guide to Herbal Safety. St Louis, MO: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005.

- Gorski JC, Huang SM, Pinto A, et al. The effect of echinacea (Echinacea purpurea root) on cytochrome P450 activity in vivo. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;75:89-100.

- Molto J, Valle M, Miranda C, Cedeno S, Negredo E, Barbanoj MJ, Clotet B. Herb-drug interaction between Echnacea purpurea [sic] and darunavir/ritonavir in HIV-infected patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2011;55(1):326-330.

- Budzinski JW, Foster BC, Vandenhoek S, Arnason JT. An in vitro evaluation of human cytochrome P450 3A4 inhibition by selected commercial herbal extracts and tinctures. Phytomedicine. 2000;7(4):273-282.

- Gurley BJ, Gardner SF, Hubbard MA, Williams DK, Gentry WB, Carrier J, Khan IA, Edwards DJ, Shah A. In vivo assessment of botanical supplementation on human cytochrome P450 phenotypes: Citrus aurantium, Echinacea purpurea, milk thistle, and saw palmetto. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2004;76:428-440.

- Penzak SR, Robertson SM, Hunt JD, Chairez C, Malati CY, Alfaro RM, Stevenson JM, Kovacs JA. Echinacea purpurea significantly induces cytochrome P450 3A activity but does not alter lopinavir-ritonavir exposure in healthy subjects. Pharmacother. 2010;30(8):797-805.

- Toselli F, Matthias A, Gillam EMJ. Echinacea metabolism and drug interactions: the case for standardization of a complementary medicine. Life Sci. 2009;85:97-106.

- Glick D. The root of all evil. Women Outside. Summer 1999:71-78.

- Hurlburt D. Endangered Echinacea: what threat, which species, and where? UpS Newsletter. Summer 1999:4, 6.

- Salac SS, Traeger JM, Jensen PN. Seeding dates and field establishment of wildflowers. HortScience. 1982;17(5):805-806.

- Price DM, Kindscher K. One hundred years of Echinacea angustifolia harvest in the Smoky Hills of Kansas, USA. Econ Bot. 2007;61(1):86-95.

- Li TSC. Echinacea: cultivation and medicinal value. HortTechnology. 1998;8(2):122-129.

- Shalaby AS, Agina EA, El-Gengaihi SE, El-Khayat AS, Hindawy SF. Response of Echinacea to some agricultural practices. J Herbs Spices Med Plants. 1997;4(4):59-67.

- Bauer R, Remiger P. TLC and HPLC analysis of alkamides in Echinacea drugs. Planta Med. 1989;55:367-370.

- Wills RBH, Stuart DL. Alkylamide and cichoric acid levels in Echinacea purpurea grown in Australia. Food Chem. 1999;67:385-388.

|